CLIMATE FINANCE | SAGARMATHA SAMBAAD | CLIMATE-INDUCED DISASTERS | LOSS & DAMAGE FUND

As Nepal battles extreme weather events worsened by disasters and loss and damage from the plains through the hills and mountains, the country geared up to televise its first bid to become a ‘climate leader’, which went live on May 16.

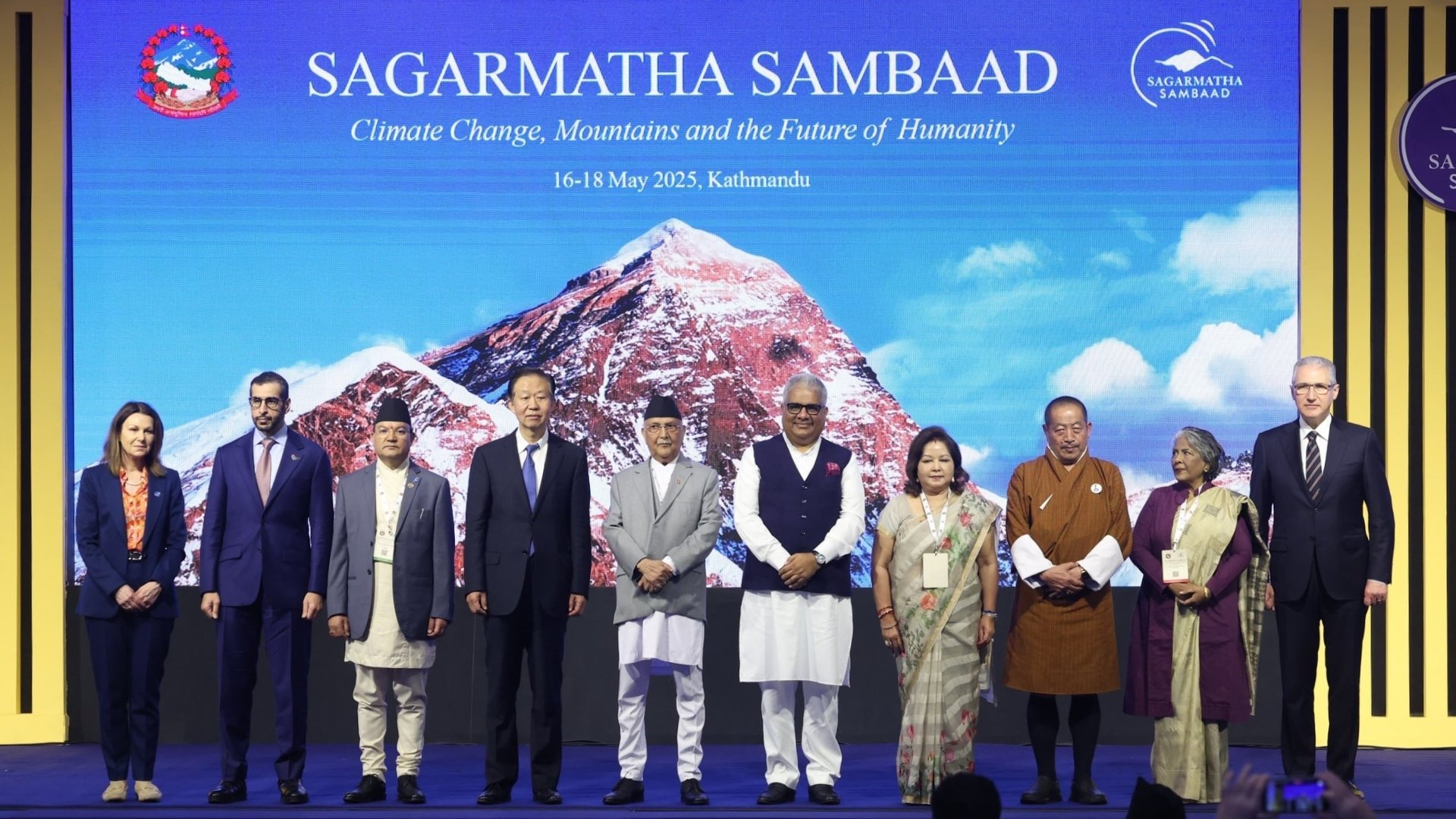

Nepal is currently holding the inaugural edition of Sagarmatha Sambaad, which has been postponed since April 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The government-promised country’s flagship multi-stakeholder dialogue aims to discuss climate change, its impacts, climate justice, climate finance, and related issues until May 18.

With the theme ‘Climate Change, Mountains and the Future of Humanity’, the country invited heads of state and governments, intellectuals and other stakeholders from around the world.

The event hosts 350 participants in total, including ministers, senior officials, diplomats, development partners, climate experts, and civil society representatives, Foreign Minister Arzu Rana Deuba briefed the press on Monday.

Meanwhile, the same day, over 50 people gathered to pay tribute and mark the accelerating disappearance of Yala Glacier, one of the Hindu Kush Himalayas’ most-studied rivers of ice in Langtang, located about 5,000 metres above sea level.

According to ICIMOD, Yala has shrunk by 66% and melted and moved backwards 784 meters since the 1970s. It is likely to be Nepal’s first to be declared ‘dead’ as glaciers vanish around the world.

Despite such alarming signs, high-level political participation is missing in the upcoming Sambaad, which should be noted firmly, highlights Climate and Environment Expert Ujjwal Upadhyay.

“None of the heads of state are coming, the highest-level of attendees are the environment minister or former residential representative to the UN,” he adds, casting doubts on global leaders’ intent and focus on climate finance, further adding that climate should not be viewed in isolation, as geopolitical stakes play the most.

Meanwhile, the country released its latest policy and programme for the upcoming FY 2025/26 two weeks ago promising improved access to climate funds, mobilising development cooperation, including implementing a long-term strategy to becoming net zero emitter by 2045. However, there’s little the Sambaad may do.

China and India, the top and the third most emitters, have pushed their target to 2060 and 2070, respectively. The United States, the European Union and Russia are among the top five emitters. All top emitters are on the flashpoints of war, gearing up for enhanced security and defence measures, prompting increased defence spending while the world grapples with economic slowdown.

Additionally, the United States has yet again withdrawn from the Paris Agreement—a milestone document promising climate finance and justice for developing and climate-vulnerable countries.

“When major chunks of powerful countries’ finances start getting funnelled into defence, then climate doesn’t get the space it needs. We need to understand this bitter reality,” said Upadhyay, adding the world is not achieving the 2050 net-zero target, let alone the $1.3 trillion commitment materialising ever.

But pressing for net-zero policies is a needless priority strain for Nepal given its negligible contribution to global emissions. The country is paying the price for these large emitters, including 36 companies that produce half the global emissions—not in kind but climate-induced disasters, causing heavy loss and damage and racking up massive economic costs.

Take for instance, increasing disasters globally, including Nepal. Among them is the climate-induced disaster last September, which eroded Nepal’s key road infrastructure—the BP Highway and left Nepal struggling for its reconstruction finance. A multi-stakeholder roundtable on climate-induced disaster risk and resilience and innovative climate and carbon financing, among others, is set for the second evening of the Sambaad as the public simultaneously continues to endure treacherous travel routes.

“Instead of putting so much effort into achieving net-zero, what we should be focusing on is anticipatory action, which I found entirely missing in the Sagarmatha Sambaad,” said the climate expert.

The policy and programme mentions that climate adaptation and mitigation programmes will be implemented based on the ideas shared in the Sambaad. But idea-sharing is not likely to help.

Globally, the talk is still about mitigation, adaptation, and resilience, said Upadhyay. “But if we truly care about climate justice, then anticipatory action must become the priority, which a study shows that for every one unit of money invested in such action prevents potential loss of seven units.”

Until Tuesday, the BP Highway faced a 17-hour vehicular halt after rain-swollen Roshikhola swept a diversion at Mapti in Roshi Rural Municipality, Kavrepalanchok.

“In Panauti, when it rains, the Roshi floods. Why haven’t we installed a high-quality automatic weather station there yet? It would cost no more than NRs 1.5 million,” he said, adding: “Had we done that investment and installed sirens in Dhulikhel, we could have saved thousands of people and vehicles from getting stranded.”

That’s what anticipatory action looks like, he highlighted, drawing an example from Kanchanpur district, which recorded the highest ever rainfall in Nepal last monsoon—500 millimetres in 24 hours.

While Kathmandu suffered 43 casualties due to heavy rainfall-induced flooding, there were none in Kanchanpur. “There was not a single casualty. Why? Because the rainfall was predicted, and the local government, APF, and Red Cross acted in advance.”

Upadhyay emphasises precise weather forecasting systems to take anticipatory action to dodge monsoon-induced disasters. “Nepal’s weather forecasting has improved, but it’s still not up to the mark. Without precise forecasts, our anticipatory systems will never be effective.”

From small investments in anticipatory models like the automatic weather station to the need for substantial funding to rebuild its vital infrastructure as BP Highway, Nepal sits at the crossroads—balancing between self-reliant financial management and donor dependency.

For instance, Japan has reportedly agreed to provide NRs 2.63 billion in grant assistance to reconstruct 3.2 kilometres—from Dalabesi to Barkhekhola—of the highway following Nepal’s insistence. It is the third time the Japanese are taking up the job following its original construction completed in March 2015, and post-earthquake reconstruction completed in 2021.

Winding through the fragile Chure and Mahabharat hills, Nepal’s most ambitious highway looked scenic—but building it was anything but. Carved from unstable rock and soil, the road took nearly two decades, demanding precision, patience, and a steep price. Yet, the dependency not only testifies to the country’s failure in learning technology and ramping up its construction abilities, but also shying away from anticipatory action.

This pattern of dependency extends beyond infrastructure. In a recent episode, the government accepted 15 electric vehicles as a grant from India to help the Sambaad logistics.

Dr Biswash Gauchan, economist and executive director at think tank IIDS, wrote in a LinkedIn post, “Accepting the vehicles worth merely NPR 40 million as a grant for a high-profile international event is a stark reflection of our deeply impoverished mindset.”

He reiterated that Nepal has an annual budget of NRs 1.86 trillion, receives NRs 180 million in remittances “every hour”, and foreign reserves currently exceeding $17 billion.

Foreign Minister Dr Arzu Rana Deuba on the other hand called it “a shared commitment to environmental sustainability and regional collaboration.” However, leading the flagship event with such a token only exposes needless reliance, putting the country’s intent, commitment and priority in question.

There’s much more on the table for “shared commitment” with the world. From the COP29 presidency, Azerbaijan’s special representative of its president, to Oman’s ambassador to India gathering in Kathmandu to discuss climate futures, Nepal must confront a multifaceted dilemma—dying glaciers, eroding roads, and drying up water tables, amid a stark reality of sliding spending on the environment in the last decade and shifting international priorities. The ongoing Sambaad must go beyond symbolism and tokenism.

Read More Stories

Kathmandu’s decay: From glorious past to ominous future

Kathmandu: The legend and the legacy Legend about Kathmandus evolution holds that the...

Kathmandu - A crumbling valley!

Valleys and cities should be young, vibrant, inspiring and full of hopes with...

Consumer Court rulings spark nationwide doctors’ strike

Doctors across Nepal suspended all non-emergency medical services on Monday in protest against...