Sustainable Development | Finance | Urbanisation | Planning

Kathmandu: The legend and the legacy

Legend about Kathmandu’s evolution holds that the valley was once a huge lake some thousands years ago. A visiting Buddhist saint Manjushri cut through the Chobhar ridge with his mighty sword Chandrahas and allowed passage for the lake water.

While the myth of Manjushri in its entirety is a fascinating tale, geological study corroborates the valley’s past as a lake. As the lake water drained over the years, civilisation began and thrived in the valley’s rich land augmented by the flowing river stream and mild climatic conditions. Ever since, the valley cultivated rich civilisation under different kingdoms.

From Lichchhavi to Malla and then to Gorkha Kingdom, the valley’s fertile soil and its location as Indo-Tibet ancient trade route helped kingdoms to reinforce their reign and civilization to flourish. The valley saw its economic and urbanistic pinnacle mainly during the Lichchhavi and Malla era. Impeccable skills at the hands of its people - mainly the Newas - in art, sculpture, architecture and cuisine who were also industrious in agriculture and trade generated ample wealth and farm surplus, reinvested into building cultural and architectural treasures.

Those treasure troves including other ancient heritages still capture the essence of today’s Kathmandu - seven of them feature as world heritage sites. Kathmandu is built of squares, palaces, stupas, temples, culture, festivals and jatras, stone spouts and ponds and other monuments that reflect the valley’s glorious cultural and architectural high point. Unique styles of architecture strikingly peculiar in the forms of pagoda, stupa, chaitya and shikhara and elaborate inscriptions of flowers, snakes, deities, including Manjushri and demigods in thangkas, statues, woods, stones, clays, and metal abound in the works of architects, sculptors and painters.

Apart from its heritage, the valley also relishes a special natural combination – it’s surrounded by foothills of the Himalayas - Nagarjun, Shivapuri, Chandragiri and Phulchowki – with exceptional seasonal weathers.

A missed opportunity of a generation

Even some decades ago, all these features remained untainted. Kathmandu’s aesthetic quality was intact. Fascinated by its radiance and exoticism, people from different corners of the world, from Tony Hagen, Boris Lissanevitch to Ulrich von Schroeder, were amazed with what they saw. Travellers documented in lengths about monuments that displayed captivating fusion of enigma with art and architecture and about people’s simple lifestyle to their rich and unique culture.

Elements of modern cities already existed back then. Areas for towns, farming and economic activities such as local small industries were fairly zoned. Newari style of collective residences with courtyard at the centre (bahal) for community living and traditional but meticulously designed houses speaks volume about their precision and sophistication in architecture and residential planning.

A complex network of water stone spouts (hiti / dhunge dhaara) that served water supplies to valley residents is another marvel of the era. Open public spaces, brick or stone-paved alleys and public resting structures such as patis, dharmasalas, sattal and mandapas for elderly, travellers, pedestrians, and residents, as public goods are other fine examples that our predecessors were way ahead in their urban planning, which had community thinking as its heart.

Some of these heritages still stand tall enough, as open repositories of great knowledge and inspiration to build future cities.

On top of that, there were vast swaths of arable land. Even if portions were to be devoured and turned into modern futuristic urban centres, it offered everything for urbanists and planners with vision, creativity and imagination. Kathmandu could have turned into one of the finest megalopolises in the world. Opulence would have inevitably followed.

In time, those swaths of tillable land disappeared. Inconsistently erected concrete built-up areas piled up there instead. Water stone spouts that once streamed crystalline water through its complex and enigmatic network of underground conduits have become dysfunctional and are disappearing. Instead, there is a deepening water crisis.

Many other conclusive grounds assert that Kathmandu’s legacy and heritage is depleting at an unprecedented level, and it sits at the verge of breakdown.

Cultural heritages still exist but seem misplaced amid unpleasant sight of crowd, dust, dirt and concrete, and although they draw admiration, the valley, as a whole, is loathed for its inability to evolve. It is equally disturbing that the ruination continues. In hindsight, a rare opportunity to build some finest cities, with imprints and inspirations from the past, was squandered just like that.

If not some splendid transformation, why couldn’t Kathmandu’s evolution be, at least, minimalistic?

To summarise it bluntly, Kathmandu’s present state is not just about incompetence, but also sheer negligence, greed and folly on the part of its planners, corporations and people.

What happened? How did we end up in the present state?

Kathmandu’s major urban transformation happened post 1990. Urbanisation had already accelerated before that, development was already centralised, and it was already a cultural hub too. As for political activity, Kathmandu has always remained the nucleus. Yet population explosion wasn’t as severe.

Post 1990s, after Nepal pursued privatisation policy and Maoist conflict started strangling livelihood at regions outside Kathmandu; a gradual exodus to Kathmandu began. Its appeal as the ultimate destination needs no elaboration.

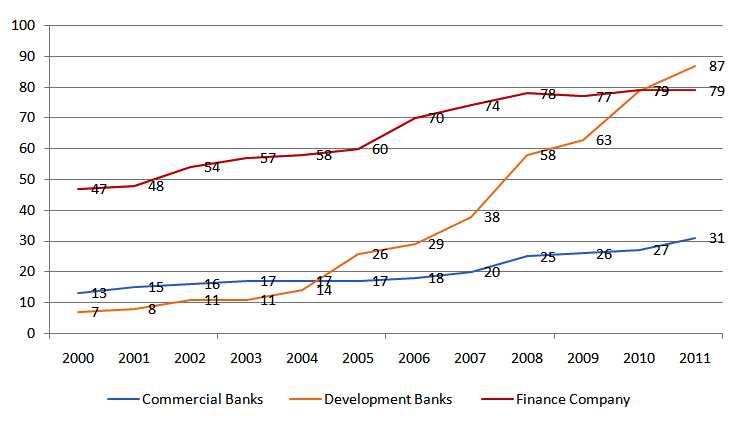

Chart 1: Urban Population (% of total population)

In brief, critical infrastructures and services and economic opportunities were all centralised while rural regions were stripped off from socioeconomic development and left to disappoint and fail. As Kathmandu remained untouched by the menaces of the armed conflict and natural disasters, it also drew people seeking refuge and security.

The development trend has slightly decentralised today while the political and economic power has also devolved, but its centrality still exists, more so due to the concentration of large dynamic populations that also make it the most attractive market.

Back then, Kathmandu had no plans about managing its carrying capacity even at the face of looming population explosion, set in motion by the rural-urban migration and its own natural rate of growth. History, both distant and recent, is a cold witness that Kathmandu, as a political centre, worries little about everything else other than power and politics. Meanwhile, local representatives were absent between 2002 and 2017 due to political upheavals and local transition.

With inbound migration, demand for physical infrastructures propelled. As its unplanned economy, with ubiquitous loopholes, couldn’t accommodate the mass influx, the shadow economy started gaining a foothold too. Post-2000, Kathmandu also saw rapid emergence of private transport as decent public transport services were absent.

As evident, none of those transformations were rooted in sound physical development planning (PDP) and foresight. Governments and people hardly bothered about any scientific basis for urban and local economic management, land-use and land fragmentation, and physical developments, public goods and related essential services.

As such, urbanisation was left to the free will of individuals and untamed market forces without a modicum of oversight, while public goods and utilities were entirely overlooked.

The business of banking and lust for land

Naturally, Kathmandu turned into an alluring proposition. From politicians to bureaucrats and big and small-ticket business persons to foreign emigrants and their families back home, everybody held a deep-seated desire and ambition to own a piece of Kathmandu.

Land was not just some investment avenue whose value would soar in a few years and never decline. For many households, building their dream home in the valley was the end goal. In addition, lands provided further financial cushion as banks wouldn't lend without land as collateral.

Chart 2: Rise in Number of BFIs

As such was the socio-economic situation, so began the deepening of credit into the real estate and housing market beginning from early 2000. The period was marked by mushrooming of institutional financial lenders (see chart 2 & 3) and low real interest rates (see chart 4).

With their tacit strategy of finance financing finance, lands sold like hot cakes as the lenders flushed the market with easy credit flows for both buyers and the sellers of land, houses and buildings. As land prices grew staggeringly, some 300 percent since 2003 (to when??), says reports in ambiguous fashion; there were explosive gains to be made. It not only stoked a real estate bubble, the period also saw the deformation of the valley to an entirely another level.

Chart 3: Expansion of BFIs branches in Kathmandu Valley and their concentration ratio

Chart 4: Dwindling real interest rates

The extent

As of mid-April 2021, 11.4 percent of BFIs’ total credit flows of Rs 4,022 billion outstanding credit are lent to the real estate sector and home loans. The credit exposure was much larger during the 2000s, mainly concentrated in Kathmandu which held much of the country’s power and wealth at the time.

Real estate sector lending of commercial banks stood at Rs 1.4 billion in mid-July 2006. By mid-July 2010, it had reached 37.97 billion, a staggering growth of 2,600 percent in a four year period. Financings were made in the construction sector too – composed of residential and non-residential construction, which had grown from 12.73 billion to 44.73 billion in the same time period.

These were only commercial banks’ lending. Although there is no disaggregated data in the central bank’s domain for development banks and finance companies for the period, studies and events corroborate that they too were aggressively lending to the sector.

For instance, a 2011 case study by the NRB found that the real estate exposure of commercial banks was 32.4%, finance companies had 27.5% and development banks had 24.1%. Banks, real estate developers and investors chose the sector because alternative investment opportunities were lacking, says the study. In the same year, Vibor Development Bank almost collapsed due to its vast credit concentration to the volatile realty market that weakened its liquidity position. NRB intervened as the lender of last resort, and saved the day. Other BFIs got into similar trouble where NRB applied different liquidity interventions.

It is no secret that massive amounts of loans such as personal, business and industrial facilities were misutilised and directed to the real estate sector, which not only underreported the data but also concentrated the flow of funds into one sector, basically unproductive, and risked the system.

Realising the associated systemic risk from credit concentration and loose lending policy, also accounting the 2007/08 global financial crisis that resulted from subprime lending in the housing market, NRB had previously directed BFIs to limit their real estate exposure within 30 percent by mid-July 2011 and 25 percent by mid July 2012. As the lending was too large to cut back immediately, the deadline was then extended to July 2013 (you can observe gradual fall in the exposure in the Chart 5).

Chart 5: Real estate exposure of commercial banks (July 2009 - Jan 2014)

Other influential players in creating the bubble were Kathmandu-based saving and credit cooperatives (SCCs), some of whom are quite massive in business size. From early 2000 to till date, these SCCs were found maintaining vast exposure to the volatile sector by skipping prudent lending practices, and even misutilising funds.

A report prepared by Gauri Bahadur Karki in 2014 to probe cooperatives’ fraud, mainly the Oriental SCC scandal, concluded that a large amount of cooperatives funds landed in trouble because of their vast exposure to the realty sector.

Clearly, the financial regulator didn’t care enough on diversifying products, investments and geographical reach. Sensing the opportunity for quick returns and high profits, financial firms made easy and imprudent lending without setting right priorities.

Large exposure to real estate meant large liquidity flowing to a mismanaged sector as real estate. Many studies have reported that authorities like the ministry of urban development had no strategic plans to address housing, business and physical development needs of the valley.

On top of that, the loose urban financing stood in stark contrast to the government’s conservative and uninformed financing priority. Government budget allocation to housing and urban planning was 18.5% during the period of fifth periodic plan (1975-80) which had reduced to 0.5% during the period of the tenth plan (2002-07).

Inevitable happened. Demand skyrocketed while private finances streamed unbridled. As a result, the asset bubble set in. Financiers, speculators, individual sellers and developers found a perfect opportunity to leverage the regulation-and-oversight-free environment to their own advantages.

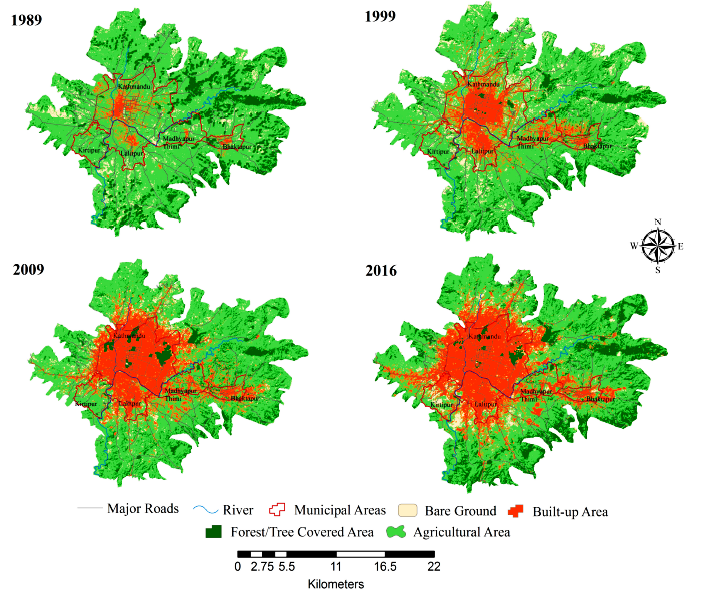

The phenomenon heavily influenced indiscriminate agriculture land conversion, land fragmentation and peripheral sprawl. Studies show that the valley underwent severe change in its urban morphology during the period, with the spread continuing further.

One study shows that Kathmandu Valley’s urban area expanded by 412% between 1989 and 2016. Expansion was 117% between 1999 and 2009, which devoured 18% agricultural lands.

Kathmandu Valley Development Authority (KVDA), the authoritative body setup in 2012 to prepare and implement Kathmandu’s physical development plan, has also disclosed similar stats in its master plan – ‘Vision 2035 and Beyond’. “The valley’s built-up area increased from 66.54 sq. km. to 118.65 sq km between 2000 and 2012, around 80% of which were residential”.

Around 70,090 houses were built in Kathmandu Metropolitan alone between 1999 and 2020, reports another study. “The number of houses is seven times more than the metropolitan’s capacity, which spans across 50 sq. km.”

Image: Land Use Land Cover Maps of Kathmandu Valley for different years

After all this, when the bubble burst, the financial sector managed to emerge scot-free, while the policy flaw led to an unprecedented urbanisation shift changing Kathmandu’s landscape forever.

These market forces, aided by lack of regulation and oversight at all levels, played a significant part in transforming Kathmandu into crass urban modernity. Crass because there was complete absence of fusion between local, traditional and modern materials, technology and architecture and thinking.

The madness also further cemented land’s prominence in the already land-obsessed valley. Effects are still observable as land prices are unreasonably high compared to the economic fundamentals. At such prices, it is almost impossible for both the private sector and the government to pool parcels of land and develop sustainable infrastructures. Evidently, mindless land conversion and fragmentation haven’t stopped either.

Sprawling cities; expanding risks

Kathmandu’s inability to learn from its past and misadventure with policy and planning has led to an insatiable land demand, which it meets through urban sprawl to the periphery. The extent is not only chilling; it can amplify the effects of any disasters to extreme severity.

In the last five years itself, Kathmandu has seen it all - the devastating 2015 earthquake, erratic monsoon induced flood, the wildfires, the mounting pollution level and the ongoing pandemic – all of which have left Kathmandu reeling under fear and anxiety. Disasters are not only recurring, their effects are becoming pronounced due to the state of Kathmandu’s urbanisation. On the other hand, pre and post-disaster management are only proving too challenging.

During the 2015 earthquake, people yearned for open spaces while the crammed cities left a troubling psychological scar. The subsequent economic blockade taught the essence of self-reliant economy, decentralisation and efficient supply chain management to mitigate the effects of supply shocks such as food and fuel inadequacy and inflation. Kathmandu’s ever rising pollution and recent wildfires are now choking the valley.

The ongoing pandemic is showing us again how Kathmandu’s wrongly built cities are ill-equipped to combat and cope with turbulent times, mainly because of their crammed, haphazard and sprawling features.

For Kathmandu, any future crisis will only get complex to manage and have severe consequences in view of its resource constraints and local government's incapacity, rising inequalities, and lack of disaggregated data about vulnerable sections of the society.

After all this, where are we headed?

When assessing the past and present planning, priorities and trends, the future looks bleak. Instead of addressing the elephant in the room, urban planners like KVDA are planning satellite cities at the outskirts of the valley covering an area of around 16,000 acre. Other large infrastructure plans like the Nijgadh International Airport, Kathmandu Outer Ring Road and Kathmandu-Terai fast track all lead back to Kathmandu. It is certain these mega urban plans will further deplete Kathmandu’s natural capital and heritage.

There is another extremely serious problem. Kathmandu’s rise as an urban hub and a financial centre is misinterpreted by the emerging metropolitans and municipalities, both urban and rural, as ‘development’ and ‘prosperity’. Despite its flawed, obsolete and unsustainable characteristics, the entire country is replicating it. As a result, urbanising trends have intensified outside the valley too, driving nation-wide urban sprawl and reduced sustainable thinking.

For instance, the plains of Butwal, Bharatpur, Tulsipur, Biratnagar, the hilly terrains of Dhadingbesi, Barpak and Beni and even mountainous places like Namche Bazaar give impressions of Kathmandu-like development model – unplanned, unsustainable, untidy and unhealthy - piling concrete structures at the expense of critical resources and aesthetics that are inheritable from local and traditional knowledge and architecture.

All this makes Kathmandu a microcosm of a much larger problem - it isn’t the only one deforming to worse anymore, the entire nation is.

Thinking Forward

Expansions and adding further infrastructures, or even the idea of them, can translate into ruining what is left of Kathmandu and lead to more population diversion and environmental and economic losses.

What it requires instead is a right, comprehensive and bold set of structural policies and programmes with reforming and renewing the existing built-up areas and surrounding heritages.

For instance, land has turned scarce and ridiculously high-priced now. Some land spaces can be freed up by providing right incentives to land/house owners, real estate developers and builders to pool land and houses. Incentives may include tax exemptions, investment support, and policy and regulatory support. Freed lands can then be used to build mass, affordable, efficient, sustainable, and resilient urban blocks that fuse traditional knowledge, architecture and technology and materials.

Let us also not forget that Kathmandu is embodiment of Newa heritage. Any planning that ignores this fact, that doesn’t care to manage and preserve this splendid heritage, would be no less than a pursuit of shallow riches.

At the same time, broader policies and investments should be aimed at decelerating population growth, diffusing economic opportunities, discouraging use of private vehicles and forging public-private partnerships in development of required infrastructures.

In all that, the central focus should be aligned to ecological thinking – how to put less stress on critical natural capital as land, forest, air and water and reduce the likelihood of ecological disasters, food insecurity and water crisis.

It’s time better sense prevails in this land-obsessed land. The clock is ticking!

(This piece was edited on 14th May 2021)

Read the first part of this story here --> Kathmandu: A crumbling valley!

Read More Stories

Kathmandu - A crumbling valley!

Valleys and cities should be young, vibrant, inspiring and full of hopes with...

The majestic Upper Mustang and its water troubles

The wind stirs heavily across the barren landscape as our bus pushes along...

Visit visa probe committee faces crisis of credibility

A day after the government finally formed a high-level study and probe committee...