Wildfire | Disaster | Environmental loss | Economic loss | Climate change

Shortly before noon on April 30, residents Ramesh Pahari and Shankar Pahari with a dozen people entered the Kumariban Community Forest to protect the Tapeshwardham Mandir in particular from a wildfire.

The fire broke out in the forest in Godawari Municipality-4, Badikhel in Lalitpur — following a series of wildfires in the nearby community forests of Jay Bhadra (Ward 3), Charghare (Ward 5) and Mahadev Khola Satya (Ward 10).

Shankar died the same day as a result of the fire, while Ramesh succumbed to his burn injuries the next day at the Cleft and Burn Center in Kirtipur. Although wildfires were not new in the village, this was the first time there were human casualties. Firebreaks about 10-15 feet wide were drawn, preventing the fire from wiping out the settlement.

According to Sanu Bhai Nagarkoti, ward chair of Godawari-4, who was also at the incident spot, one individual was rushed to the healthcare facility as he struggled to breathe due to the plume of smoke. Others faced the same but needed no immediate healthcare attention.

While the forest was burning, Badikhel was covered with thick plumes of smoke, resulting in short-term yet hazardous health complications among the residents. Tej Prasad Dhamala, chief at Badikhel Health Post, informed the_farsight that the health post reported more than usual out-patient inflow during the wildfire.

“Shortness of breathing, eye burn, dry cough were some common complaints handled at the [health] post,” said Dhamala, adding further that a few patients were referred to Patan Hospital. Upon prescription from there, they were put on nebulisation. Residents with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) were reported to suffer more, he added.

On the other hill face of Badikhel and at the feet of Anandaban forest in Lele, Godawari lies Anandaban Hospital which survived wildfire on April 30, fortunately, without any human or property loss.

Estimates were that the fire would reach the hospital in three to four days following sights of wildfire at a distance the previous day. About 10 metres wide fire lines were drawn in the Anandaban forest with the help of security forces to secure the hospital — which has a capacity of 110 beds followed by 150 technical and non-technical staff.

Sher Bahadur Gurung, head of the hospital administration, told the_farsight that at least 15 patients admitted to the leprosy department however had to be shifted to a distant rehab building in Sunakothi, Lalitpur. The fire that raged in the morning was taken under control by the evening with the help of local administration and security forces, he added.

On the other hand, staff and patients reported facing health issues similar to that of the residents of Badikhel due to plumes of smoke that covered the hospital premises for at least two days.

These are instances of wildfire and their consequences reported in one municipality located in the Capital Valley.

A prolonged dry spell last winter had already worried environmentalists about the intensity of wildfires — a yearly post-winter and pre-monsoon disaster — coming summer. There were public warnings and calls for preparations at official meetings and in media reports urging for greater resource mobilisation amid visible trends of rising raging wildfires in the recent times.

Their fears eventually materialised.

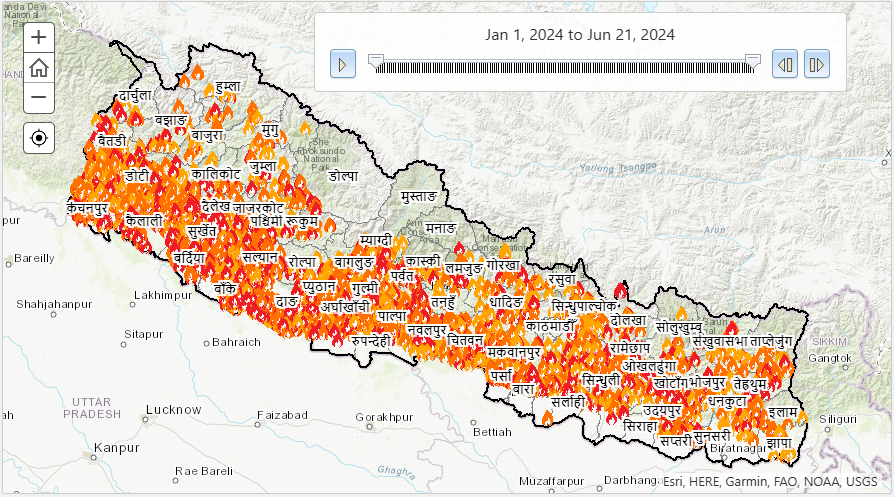

The country reported a record-breaking blaze in more than 50 districts this year, killing 17 people including three Nepal Army personnel. By June 21, 2024, Nepal recorded 5,125 incidents of wildfire. As of now, wildfires have subsided, while the country faced troubles with monsoon-induced disasters such as floods and landslides, which killed about 500 people this year.

Neglect amid lack of economic data

The scale of the destruction wrought by these wildfires is staggering.

According to data compiled from various sources, 139 people have lost their lives to wildfire incidents across the country between 2008 and 2024 (in 17 years), out of which 38 were killed in the last four years.

Source: Sundar Sharma, Fire Expert at NDRRMA (2008-2012) | *Data for 2013 is unavailable

With increasing wildfire incidents, there is another valuable resource at severe risk — forests.

Around 6.2 million hectares of the country’s land area is forest, according to a 2018 report by the Forest Research and Training Center. The report excludes forests including shrubs inside the Protected Areas and Development Council Land. The country’s forest cover almost doubled between the period of 1992 and 2016 from 26% to 45%, according to a study that mapped tree cover based on Landsat images.

This increase in Nepal’s forest cover is the result of sustained investment and conservation efforts over several decades mainly through its community forestry programmes, following significant losses experienced between the 1950s and 1980s. Now, the persistent large incidents of wildfires are threatening forest recovery and conservation, however [see table below for the number of incidents].

Almost 21,000 wildfire incidents were recorded between the period of 2019 and 2024 alone. A study shows that the total burned area has increased by 0.6% annually since 2001 while losing nearly 40,000 hectares of forest area annually. NDRRMA puts the estimate of annual forest loss at 200,000 hectares although it doesn’t mention the time-series or source for this.

Source: Department of Forests and Soil Conservation | Sundar Sharma, Fire Expert at NDRRMA (2008-2012)

When a tree burns

The types of changes in a tree following a fire depend on the extent of flame and damage caused.

If a tree (including roots) burns down and all its tissues are destroyed, a regeneration let alone restoration of the tree is impossible, says Brajesh Shrestha, lecturer at Bhaktapur Multiple Campus. For a partially burnt tree, regeneration and restoration may take a longer than usual time.

In the case of herbaceous plants, stems lying underground following surface burning help regenerate and restore them, he added.

Shrestha, who is also Subject Coordinator Biology at St. Xavier’s College in Maitighar Mandala, Kathmandu, explained a phenomenon, particularly due to large and intense wildfires.

“A total burning destroys the greenery of trees, emitting carbon which contributes to global warming and thus disturbing the succession pattern of plants and trees,” he said. Meaning that “new species of plants and trees replace existing ones” and they follow a cycle.

When trees spread across a large area burn [due to wildfire], they lose their greenery, and emit a heavy amount of carbon which alters the order of weather (and eventually climate) and simultaneously contributes to the heating of soil. This makes it difficult for existing species to adapt to slightly altered climatic conditions, let alone regenerate and restore. Then takes over new species.

He noted this phenomenon does not occur in smaller areas and with low-intensity fire. Rather the regeneration and restoration of existing species cut down the environmental impact (carbon emission, alteration in soil nature) caused by the burning of trees.

When a forest burns, it doesn’t only consume trees. It’s a massive economic disaster too — a multifaceted one disrupting economies at local, regional, and national level. Apart from putting fire to investments made over the years, it devastates wildlife habitats, disrupts ecosystems, releases harmful pollutants in the air and sabotages nature’s balance for years to come.

When the 2009 wildfire struck, one of the fiercest and pretty rare at the time, it killed 43 individuals and left 12 injured. The fire affected 516 families, killed 375 livestock while 100,000 cattle were burned to death, and obliterated 74 houses and 22 cattle sheds, causing a total financial loss estimated at Rs 140 million.

Nepal however lacks detailed records and studies that evaluate the economic costs of these wildfires, which have grown over time. Our analysis suggests these costs can exceed annual losses by a billion rupees.

First, there is no breakdown contribution of forest alone to the GDP [which was estimated to be around 3.5%, according to a 2016 government report]. But the agricultural sector (which constitutes agriculture, forest and fishery) accounted for 24.1% and 24.7% of the total GDP In 2022/23 and 2023/24 respectively.

In the fiscal year 2022/23, the forest sector contributed Rs 4.77 billion in revenue for the government, a 13% decline compared to the previous fiscal year, which is projected to contribute six billion in 2023/24. The same year, the sector generated employment for 67,260 individuals.

But there is significant untapped potential, multiple studies show. A report on private sector involvement and investment in Nepal’s forestry in 2014 shows that Nepal could generate economic value of around Rs 373 billion from legally and sustainably produced forest products and services creating 1.38 million full-time job equivalents, around 15 fold increase from the previous value.

Forests serve as a crucial reservoir of medicinal plants that Nepal is banking on for its economic boost. Nepal’s most recent export strategies — Nepal’s both trade integration strategies (NTIS): 2016 and 2023 — recognise medicinal herbs as promising export products. The NTIS 2023 even includes a separate forest category featuring items like handmade lokta paper, rosin and turpentine, fragrant oil and textiles of long fibre.

Moreover, the September investment summit highlighted the potential for foreign direct investments (FDIs) in Nepal, showcasing the country’s 700 species of medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs).

Forests are also providers of essential ecosystem goods and services such as retaining sediment, regulating water and climate, and providing habitats; and bolstering key sectors like energy, agriculture, tourism and transportation.

For instance, forests are not only a key factor in increasing agricultural productivity, but they also draw nearly half of all foreign tourists to protected areas. However, instances suggest areas increasingly becoming vulnerable. One study shows that increasing fire incidences are causing biomass loss of 7.07 million tons per year.

While all this potential is derived from the richness of biodiversity and ecosystem where the forest is central, the extent of economic losses remains uncertain.

Pokhrel explains that the total economic loss depends on forest species. A simple example is an acre of a forest of Utis burn versus an acre of loth salla (Himalayan yew) — the economic loss would be in billions due to its medicinal value. The price tag of the ecosystems in the mountains could be in the millions. In other places, it could be less. “We don’t know how to account for its economic damage and losses,” he adds.

Anil Pokhrel, chief executive officer of NDRRMA, suggests not relying upon whatever data of estimated loss or economic loss available in Nepal’s system. The available data are mere numbers based on public complaints that local police stations and offices received, he added.

“We are realising it now and working to completely revamp how economic losses and damages register in our [data] system. But we haven’t been able to touch it much nor do we have a methodology to put a price tag on damages incurred.”

For instance, all houses burned by wildfires do not carry the same monetary value, let alone accounting for household items. The government applies a standard average rate of value, let’s say Rs 1 million each for 10 houses burned down in a settlement, meaning a reconstruction package of Rs 10 million, he explained further. Similarly, economic loss to public infrastructures, particularly during floods and landslides, varies per the type (such as bridges, roads and highways, and hydel dams) and the location of projects.

Wildlife loss is another repercussion of wildfires.

Again, there is no data on this other than unverified reports. According to a news report, monkeys, snakes, rabbits, porcupines, deer, wild boars and pheasants were among the wildlife killed in the 2016 wildfire in Bajura. Similarly, the 2012 wildfire in Bardiya National Park reportedly led to a 40% loss of its small mammals, 60% of its insects and a significant number of birds.

It’s worth noting that one of the motivations for setting fires in the wild is for poaching purposes, while national parks and conservation areas also experience increasing incidences of wildfires.

As wildfires rage, urban areas often find themselves engulfed in an off-shoot crisis with smoke choking the already polluted air — with increases in particulate matter levels in the air far exceeding typical air pollution levels and further threatening public health.

Pollution reached an all-time high in Kathmandu, where almost five million people reside. Between late April and early May, it became the most polluted city globally with AQI reaching over 200. The fate of other industrial and urban centres such as Pokhara, Bharatpur, Birgunj, Biratnagar, Butwal, Nepalgunj and Dhangadhi were similar.

Not only does this smoke have immediate health risks — cough and respiratory problems such as asthma, but poses serious long-term effects on public health, experts frequently warn, as cities choke under harmful smoke.

Wildfires generate finer particles known as PM2.5, even finer nanoparticles, four times more toxic to immune cells in the lungs, which are extremely dangerous to people with pre-existing respiratory conditions, and newborns, reports BBC. A 2022 study says that wildfires account for the emission of 3.30 million tons of carbon emission per year.

As per government data, as many as 42,100 people die prematurely due to air pollution in Nepal every year. Of these, under five children account for 19% and adults above 70 years of age for 27%. It is a major contributor to the top five causes of death, namely COPD (66%), ischemic heart disease (34%), stroke (37%), lower respiratory infection (47%) and neonatal deaths (22%); and reduces the life expectancy of an average Nepali by 4.1 years.

And as smoke settles, there is a new financial burden added to the state’s treasury for rehabilitation and recovery efforts, which amount to millions. For instance, Godawari Municipality announced a compensation package of Rs 500,000 each to the families of Shankar Pahari and Ramesh Pahari.

It’s consequences don't end there. Wildfire is also considered a major driver of land degradation, resulting in increased runoff, floods and landslides.

Floods and landslides are one of the costliest natural disasters [There was one recently]. This also makes the relationship between wildfire and the intensity of monsoon-induced disasters in the context of Nepal worth a study.

Another concern arises from the increasing fire incidences’ possible impact on Nepal’s carbon trading plans. Nepal is set to cut 34.2 million tons of CO2 in 10 years starting from 2018 to 2028 in the Terai Arc Landscape (TAL) and potentially earn up to $45 million in payments.

But 23% (7.9 million tons) of the total reduction will be held as a buffer against potential carbon releases from wildfires and loss of stored carbon.

Only recently, Nepal has signed a bilateral cooperation agreement on emissions trading with the Swedish Energy Agency on the sidelines of COP29 in Baku.

The human toll and realities it tells

Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act, 2017, carries a spirit that any event of premature death of people is a disaster, according to Pokhrel, the NDRRMA CEO.

Moreover, how these lives are lost also tell several stories about wildfire management in the country.

Seventeen people, including three Nepal Army personnel, lost their lives this year to wildfire. In the 2009 wildfires, one of the deadliest Nepal has faced, 13 Nepal Army personnel died during their attempts to put out a fire in Srithandanda Jungle in Ramechhap district.

A media report suggests that those [13 soldiers] killed in 2009 were among 150 soldiers deployed to control the fire which “trapped them from all sides after the wind changed the direction.” Security personnel from the Nepal Army [and the Armed Police Force] are trained in basic firefighting, as the report suggests, they, however, lacked the necessary safety gear to fight the Ramechhap fire.

Similarly, three soldiers in Mastabhawani Community Forest in the Dolpa district faced the same fate under a strong wind blow for a speculated lack of safety gear in 2024. Although the number appears much lesser than that in 2009, human life should not merely be a number. Especially when most of Nepal’s rescue workers and disaster fighters are compelled to work with limited resources, often putting their lives at risk.

In correspondence with BBC, Krishna Acharya, the then director-general of the federal Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation (DoNPWC) was quoted saying, “How long can we fight the fire with just soil and brooms made up of plants?” Based on our conversation with experts and local government representatives, things haven’t changed much since.

Our talk with Sanu Bhai Nagarkoti, the ward chair of Godawari Municipality-4 (Lalitpur), implied that local governments alone, be it a separate budgetary channel for resource acquisition or mobilisation, cannot handle life-costing disasters such as wildfires.

Everybody is responsible but nobody is accountable

Although there is widespread agreement on the importance of forest preservation and disaster risk reduction, accountability remains elusive, extending to bureaucracy and political leadership.

Currently, the NDRRMA under the Ministry of Home Affairs (MoHA) serves as the focal agency for all disaster management, while the Ministry of Forest and Environment (MoFE) specifically addresses wildfire disasters. Its forest department uses satellite imagery to manage wildfire observations and provide technical and financial assistance to communities to help them manage wildfire risks.

For tracking wildfire incidents at the national level, a Forest Fire Control Room has been operational since 2021 namely the ‘GIS and Mapping Section’ under the federal Department of Forest and Soil Conservation (DoFSC). A Fire Focal Person is also appointed at the department.

But, there is no dedicated unit, neither under NDRRMA nor MoFE, to look after wildfires.

The provinces have jurisdiction over the national forests through their respective forest ministry. However, the federal DoFSC presides over the role of coordinator among provincial authorities. Meanwhile, national parks (NP), wildlife reserves (WLR) and conservation areas (CA) fall under the jurisdiction of the federal DoNPWC.

CA Offices under the DoNPWC; division forest offices (DFO) and watershed management offices (WMOs) under provincial governments; and basin offices under DoFSC are responsible units in their jurisdiction areas.

Sundar Sharma, a fire expert at NDRRMA, captures this disjointed division of responsibilities succinctly: “Everyone is responsible, but no one is accountable.”

Lack of Resources

Another constraint to bringing wildfires under control is low budget, said Sharma. “If there were substantial financial resources, we could spread awareness about wildfire prevention, but NDRRMA lacks enough budget.”

In the fiscal year 2021/22, a budget of Rs 220.18 million was allocated to the NDRRMA for fire control, with a significant portion (Rs 200 million) set aside for the procurement of fire brigades. However, no budget was allocated for the following fiscal year (2022/23), and only Rs 5.5 million was provided for 2023/24, with a mere Rs 12.5 million for the current fiscal year.

While NDRRMA’s claim is true that it lacks an adequate budget, its overall budget spending, on the other hand, isn’t impressive either. The spending hovers around 50%, an indicator of low institutional capacity and governance challenges.

On this, Pokhrel explains, “Usually, it’s two things — less resources and a low budget, and an irony of not being able to spend. Not being able to secure an appropriate budget is a major problem and poor spending is another.”

On a positive note, NDRRMA hosted two fire experts from Australia, which has one of the best fire management systems in the world. “A year of research, study and valuable insights by the visiting experts can form a cornerstone in bridging the gap in Nepal’s wildfire management practices”, Pokhrel told the_farsight during an interview when preparations to invite the experts were on.

Pokhrel admits that the state lacks resources — adequate financing and technical human resources. There are global funds set up to combat disasters for vulnerable countries as grants, but securing them follows a hectic process and can take years to materialise. “The process is too bureaucratic and inaccessible for countries like ours. This needs to change. We need direct access to such funds.”

The Department of Forests and Soil Conservation (DoFSC) also receives budget allocations for wildfire-related initiatives through the “National Forest Development and Management Program.”

This fiscal year, they have allocated Rs 1 million budget for the publication, production and distribution of publicity material for wildfire control; another one million rupees for the production and broadcast of awareness audio material through community radio regarding wildfire control and prevention; and half a million budget for wildfire web information system orientation training to forest focal person of provinces.

According to a source at the federal department, their budget requests for various works including study and research and community discussions on wildfire have been rejected.

In 2022/23, the MoFE allocated a nominal budget of Rs 1 million to map province-wise wildfire risks. However, the mapping was cancelled due to the delayed release of funds from the Ministry of Finance, says the annual report of the MoFE, which highlights the sense of urgency when it comes to wildfire management.

Leadership: Missing in Action

As Nepal grappled with one of its most extensive wildfire crises peaking in April this year, questions should arise about the three-tier governments’ leadership and political inertia in responding to the catastrophe. From a period marked by political distractions to a lack of tangible action, the absence of effective governance left communities vulnerable and exposed.

In 2021, when Shivapuri National Park was burning, the government deployed a helicopter carrying water to contain the wildfire. Similar tangible action was notably missing during this year’s crisis.

When asked about this, the NDRRMA chief Pokhrel clarified that they coordinated a joint operation then with Simrik Air which came on board as a part of their corporate social responsibility (CSR). The operation at large involved forces from the Nepal Army, the APF and volunteers on the ground.

Such responses have been carried out thrice in total in Nepal’s experience with Shivapuri operation being the second, shares Pokhrel. First, in Taplejung, where the fire was about to reach the Pathibhara Mandir. “Simrik Airlines helped us by filling water from nearby Jor Pokhari.”

Third, when a factory in Tanahun caught fire, which could have spread to settlements [this case wasn’t a wildfire incident, but fire in general — a separate category of disaster]. Simrik provided a paid service for the third time.

However, our analysis compiled of media reports from across the country suggests that local governments and residents were left on their own whether and how they survived wildfires. Little over 800 elected representatives sitting across eight capitals bet their horses to stalemates in their respective assemblies.

This year, political parties appeared preoccupied with businesses such as preparations for by-elections held on April 27, deadlocks in provincial governments, and an investment summit taking place on April 28-29, diverting attention away from the pressing wildfire crisis at hand.

First, the lower house in Kathmandu faced a stonewall as the ruling and the opposition exchanged political allegations. Major controversies surrounded then Home Minister Rabi Lamichhane, who spearheaded activities related to emergency preparedness and response through agencies under his jurisdiction. It further detracted from the government’s ability to prioritise and respond to the escalating emergency.

Second, Lumbini Province faced the brunt of wildfire the most this year with over 1,200 recorded incidents peaking in April followed by Karnali and Sudurpaschim with nearly 1,000 such incidents each. Meanwhile, the government seats in Biratnagar, Janakpur, Hetauda, Pokhara, Dang, Surkhet and Dhangadhi felt tremors of federal ruling partners, asserting to hold provinces under their thumbs.

How much of Nepal’s wildfire is climate change?

The effects of climate change, such as increased temperature, drought and changed precipitation patterns, collectively, exacerbate wildfire risks by creating favourable conditions for its spread.

According to a 2017 study by the federal Department of Hydrology and Meteorology (DHM) which assessed temperature variability between 1970 and 2017, Nepal’s average temperature has increased by 0.056 degrees Celsius compared to the global average of 0.03 degrees Celsius.

Similarly, Nepal received significantly lesser rainfall in the last two winters (December 2023-February 2024, and December 2022-February 2023).

Nepal receives an average winter rainfall of 60.1 mm, which is the average precipitation over the 30 years from 1991 to 2020. However, the actual rain was recorded at 21.5% (12.9 mm) last year and 3.1% (1.9 mm) this year of the average rainfall, suggesting extreme droughts. Droughts are periods with the total rainfall below 75% of the annual average.

The overall weather pattern, including rainfall incidents, is largely influenced by two global phenomena occurring at irregular intervals of two to seven years, one at a time — El Niño lasting for six to 12 months, and La Niña for up to four years.

The El Niño effect is responsible for lesser rainfall in Australia and Asia regions, pushing a drier and hotter Winter and hence fueling the intensity of wildfires. The effect was recorded during the Winters of 2009-10 (moderate), 2015-16 (very strong) and 2023-24 (strong) — the same years when wildfires shot up in Nepal.

The effect of 2018-19 had a lasting impact as it fueled the infamous Australian bushfires in 2020, while Nepal recorded the highest-ever incidents of wildfires in 2021.

One research predicts that wildfires in Nepal will rise by 12% by 2030, 30% by 2050, and 50% by the end of the century as the climate crisis worsens in the Himalayas.

On the other hand, almost all of Nepal’s wildfires are first sparked by human activity, according to several government reports, which then are spread by winds easily igniting dry biomass. These prominently include human actions like — careless disposal of cigarette butts, the burning of dry vegetation (hays) to clear farmlands (fields) for planting new crops and managing pastures and fertilisers and intentional fires set by poachers.

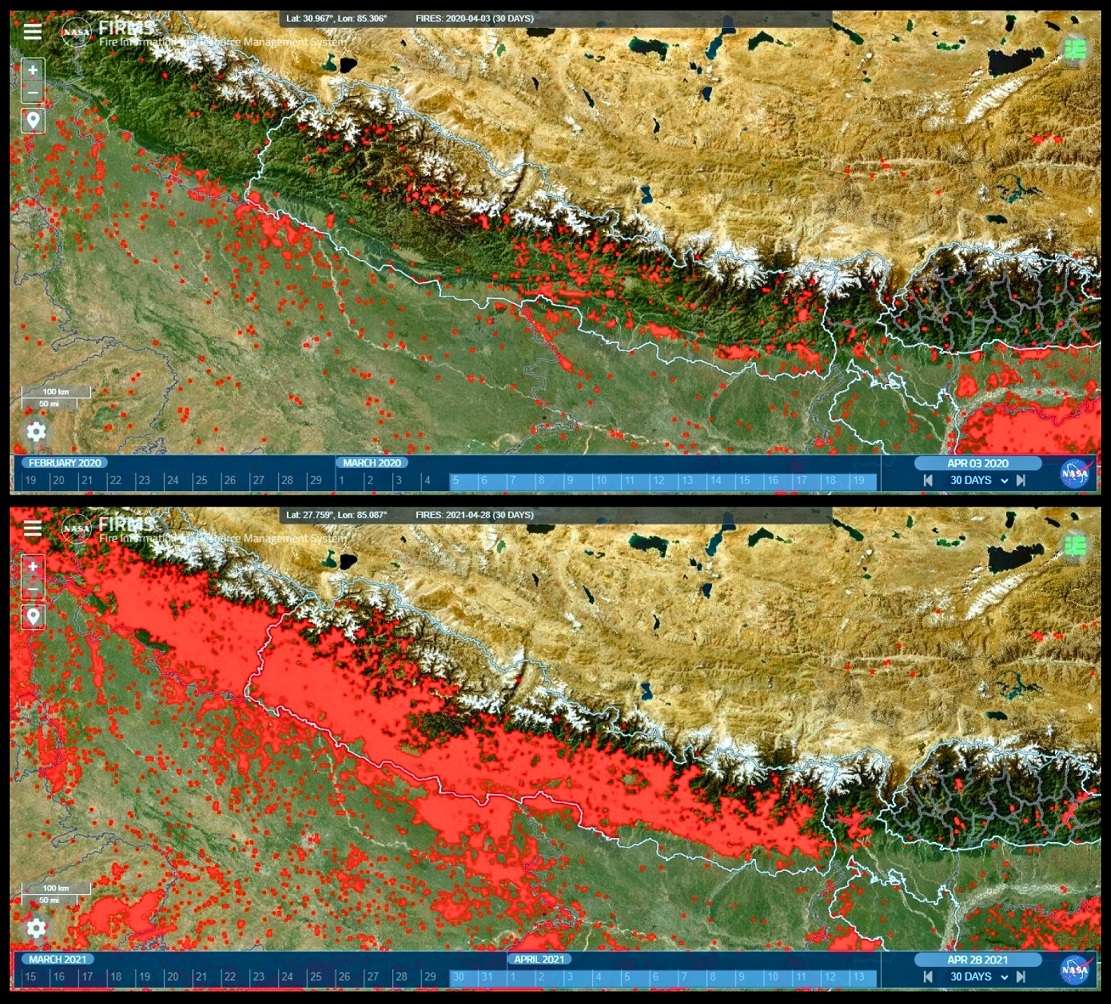

This assertion, that human actions ignite wildfires, is vividly exemplified by the following images:

The first image was taken in 2020 during the COVID pandemic when there were stringent restrictions on the movement of people. About 1,012 wildfire incidents were recorded while the satellite image under the Fire Information Resource Management System (FIRMS) shows a relatively low area covered by fire the same year.

In 2021, the situation changed drastically as movement restrictions lax and usual activities resumed. The year saw a staggering number of 6,537 incidents covering vast areas.

This stark contrast between 2020 and 2021 doesn’t imply locking people up but suggests a comprehensive fire prevention strategy, incorporating stricter laws, public awareness campaigns, community engagement and individual responsibility, construction of fire lines, early warning systems and better-equipped fire control patrol and firefighters, which of course requires wildfires to be taken more seriously first.

Read More Stories

Kathmandu’s decay: From glorious past to ominous future

Kathmandu: The legend and the legacy Legend about Kathmandus evolution holds that the...

Kathmandu - A crumbling valley!

Valleys and cities should be young, vibrant, inspiring and full of hopes with...

Today’s weather: Monsoon deepens across Nepal, bringing rain, risk, and rising rivers

Monsoon winds have taken hold across Nepal, with cloudy skies and bouts of...