Madhesh Library | Research Centre | Knowledge Power | Knowledge Production | Youth Initiative

On January 26, I rode to Kirtipur to sit with Anshu Kumar and Aavash Guru. It was a cool windy Sunday inside the Tribhuvan University premises as we talked over samosa, sel roti and milk tea at Balkumari [Khaja Ghar].

Anshu is the coordinator of Madhesh Library and Research Center (MLRC), and Aavash is its founder and guardian. Both 27 years old are from Golbazar Municipality of Siraha.

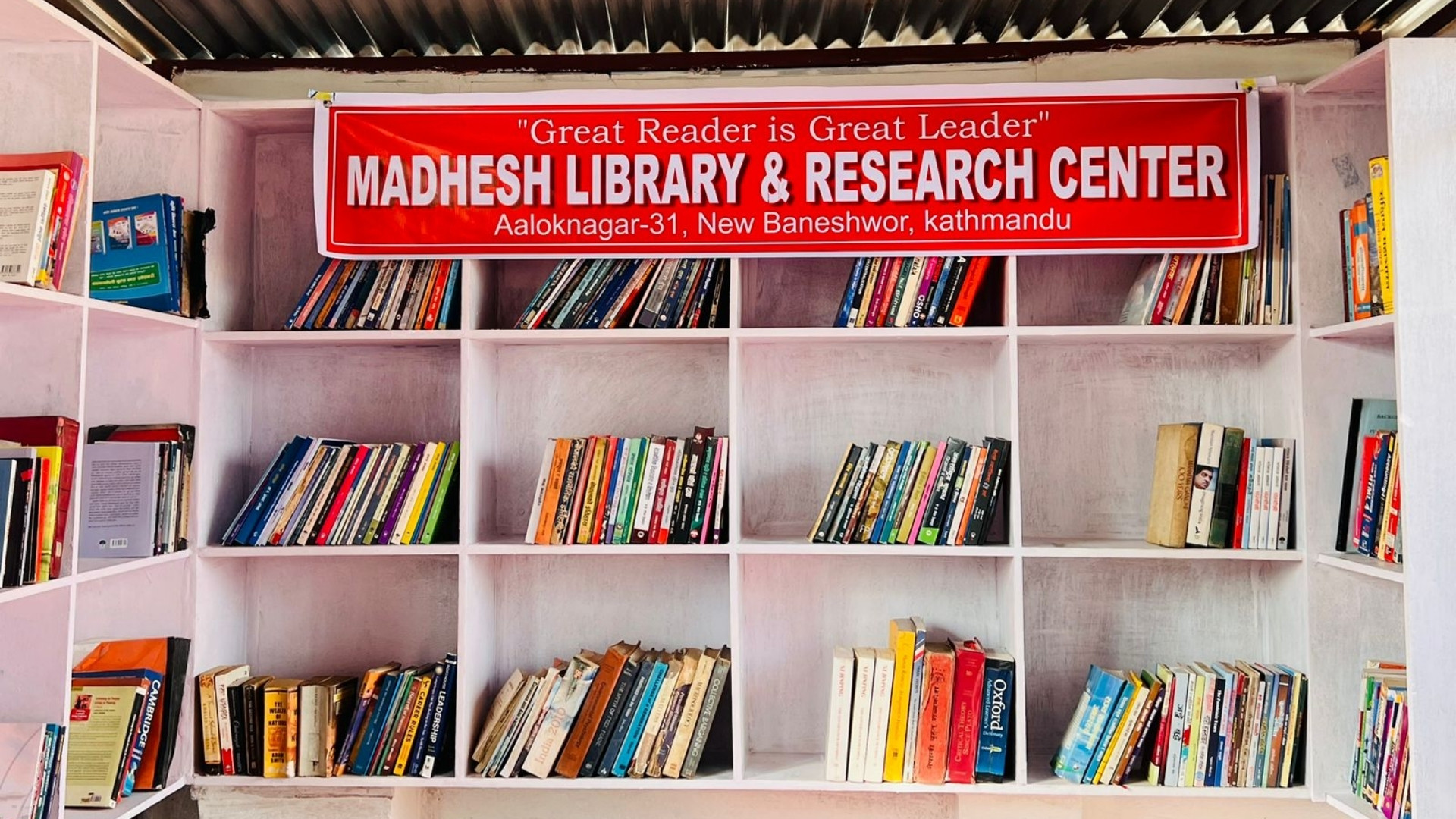

A day earlier, I attended the weekly book discussion series held at the library hall located in Alok Nagar, Kathmandu. ‘Economy of Tarai’, second chapter of the book ‘Regionalism and National Unity in Nepal’ was in discussion.

The book by Federick H Gaige, published in 1975 as his dissertation, is considered one of the few research-based resources that offers the region’s struggles and perspectives on the nation building and national integration framework perpetuated by the Gorkha-turned-Nepal state.

Gaige criticised the government policies centred on ‘one nation, one language, one dress’ and that such singular identities of Nepali nationalism imposed on the people of the region will not integrate the nation. Rather the suppression would create more political, social and economic challenges for the state in the future.

“What Gaige said 50 years ago, it’s still relevant. Madhesh still struggles to find itself in a comprehensive national framework with newer challenges now,” adds Anshu as he sips his tea.

Reflecting on the book session, we enter the domain of MLRC, established in July 2023 with the slogan ‘Great Reader Is Great Leader’. Among a few Madheshi-led institution located in Kathmandu, MLRC aims to intervene into knowledge power (or ज्ञान सत्ता) that has kept Madhesh's perspectives away from national framework, rather more often than not subjected to stigmas.

The ‘Madhesh’ in the library’s name stands for all the districts in the Terai region of Nepal — from Jhapa in the east to Kanchanpur in the west — and not only the ‘sarkari’ Madhesh Pradesh.

Aavash narrates the story behind founding of MLRC —

I and a few Madhesh-centric politically and socially conscious friends, who were by various means part of the third Madhesh Aandolan, came to Kathmandu about seven years ago. The Aandolan had subsided but without a justified closure. Nobody knew when and how it concluded.

In our analysis, it basically failed because it lacked the knowledge power to articulate its issues, concerns and interests to the state, exclusive of Madheshi decision makers. Leaders could not convince the state to deconstruct the Panchayat-made national framework that marginalised Madhesh and prove the region’s significance in a comprehensive constitutional framework.

However, various Madhesh-related programs were held in Kathmandu, often discussing superficially or dismissing the region’s issues. We realised the need for in-depth discourse. We visited Madhesh Media House where we found a comprehensive list of books on Madhesh, but none were available.

This drove us to develop MLRC where everything related to Madhesh — its history, what the region is and how it can prosper is available. Although we are in the era of e-library, contexts of Madhesh are not available online. Whatever is written is in a few books. That’s why we aim to collect all the readings on Madhesh and gradually digitalise them for better access.

In addition, the aftermath of the third Madhesh Aandolan created an ideological and consciousness vacuum with a sense of defeat. It swayed Madheshi youths, even those who were part of the Aandolan, to join religious and caste extremist outfits. This, we think, will divide Madhesh and dilute its rights and dignity movements in the future.

And it’s all because of collective Madheshi consciousness among youths going down. We aim to redevelop this consciousness and realign on fundamental issues of Madhesh through this library and research center. Moreover, Madhesh is the land of Janak, Bidhyapati and Buddha, so why not?

Anshu narrates the sociological factor behind the need of MLRC —

Kathmandu is not just a capital city, it is also a centre of knowledge [production].

Whoever identifies themselves as Madheshi in Kathmandu may have views and perspectives on issues of their region stemming from their personal experiences. But they lack broader knowledge to link their experiences with collective discrimination based on identity.

Madheshis lack leadership roles at the institutions producing knowledge for national consumption. No matter how much a non-Madheshi tries to remain neutral, their biases prevail. Subject matters that I feel, as a Madheshi, need to be researched in institutions, the other, who has not experienced discrimination as I, would not feel the need.

For instance, a few days ago, we read ‘Ambivalence denied: The Making of Rastriya Itihas in Panchayat era textbooks’ by Pratyoush Onta, because we felt the need [to learn and deconstruct nationalistic symbols and pride imposed in Madhesh through one language policy — Nepali language as sole medium of instruction across the schools during Panchayat, resulting in marginalisation of communities in Madhesh].

Nobody needs to inject a growing child with hostile feelings towards Madhesh and Madheshis. It comes to them through the textbooks thriving on the Panchayat era approach. There are several [academic and sociopolitical] loose forums and institutions in Kathmandu but they did not feel the need for such talk.

Another instance is the unfortunate incident during the NPL. What offenders did was wrong at an individual level, but we cannot solely blame them. On a macro level, most Sudurpaschim supporters were hostile [towards Janakpur since the start of the tournament]. They were subconsciously driven by the notion — ‘how can a team that represents foreign-appearing people lift the trophy on their native land?’

How was this sentiment born? It’s imperative to study. Institutions led by the Pahadi community would not feel the urge to do so. We may not immediately be able to create discourse at the scale Martin Chautari and Social Science Baha do, but we want to begin from somewhere.

Madhesh has its own needs in terms of knowledge that must be explored. Social phenomena in and around Madhesh — why are things the way they are? — must come in discourse. Additionally, most incidents that took place inside the country or related to Nepal abroad lack Madhesh's perspectives.

Anshu, drawing words from Aavash, explains about knowledge power or ज्ञान सत्ता —

Knowledge is a human product. What we perceive or undertake as knowledge voluntarily or involuntarily, including common sense, is produced. For a general example, on which side should we walk, left or right? Even, how I think is based on the knowledge produced by someone.

University is known as the centre of knowledge production. And who controls and produces knowledge shapes our conscience. For instance, although dowry is a nationwide issue, the word “dowry” has been made synonymous to Madhesh. Because the mass media has written and portrayed it zillion times establishing it as if it pervades across Madheshi families only.

It’s true that worse deformed cases, to the extent of burning alive, prevail in Madhesh. Due to such portrayal, those who talk about dowry in Madhesh, they rather mock the region than thinking about its solutions.

To have a role in knowledge production is, I think, knowledge power. And we want to intervene in the present knowledge power dynamics and production process [which is exclusively held by a limited group of hill communities].

Anshu answers what MLRC is up to these days —

Like Madhesh politics, majority youths connected with the library represent one specific district and sub-region, and caste of Madhesh. We are trying to diversify our connection. We are working to connect with youths from Dalit, Muslim and other communities, and also those in plains districts beyond the eight districts of Madhesh Pradesh. Even within Madhesh Pradesh, we have not been able to connect with youths from the western districts.

Second, we hold a regular discourse series called ‘Madhesh Samvad’, where we discuss concerns of the region. We have held 18 episodes so far.

Third, in the context of knowledge power, we believe Madhesh must read. When a Madheshi leader or a youth speaks of politics, much of the content is guided by emotions or constituted of their personal experiences. It should be more than that. They should be able to speak based on academia citing books, and facts. To develop reading and evidence-based oratory skills, we hold regular book discussion series ‘Madhesh Padhela’ — where attendees and the presenter exchange critical views on the content of the book.

We are still in bid to collect Madhesh-related books [and any form of literature] amid financial challenges. But, not all the books received from individual donors are relevant to our needs.

Anshu on institutionalising MLRC to empower Madheshi intelligentsia and role in politics —

[Context: There have been instances where well developed institutions with ambitions and themes like MLRC collapse on the whim of a few people. Leaders in bid to cash in on the collective image for personal gains — mostly political, often tore the institution’s integrity]

Everything has manifest functions (ambition) and latent functions (byproduct) in sociology. At MLRC, the manifest function is to produce conscious Madheshi intelligentsia. But we can’t control them. Even if people were to enter politics, they would be good politicians given the way they understood society. They would definitely be better than leaders driven by only emotions. This could be the latent function.

Additionally, it’s hard to keep any institution away from the shadow of politics. Members are free to be politically active but as an individual. MLRC as an institution remains inside the boundary of academia. We as an institution may write informed articles, have political opinion, organise discourse and solely engage in knowledge production. For instance, if I were to join politics, I would leave the position at MLRC. I might be known as a former coordinator of MLRC, but would not drag the institution into road politics.

Aavash on relevance of MLRC as library when reading culture depletes and libraries shut down —

If we intrigue a person about a topic or subject, s/he develops interest and begins exploring reading materials in a drive to get to the bottom of the subject. Our weekly Madhesh Samvad and Book Discussion series aim to do the same and thus MLRC as library is relevant. We are also working to build an e-library for wider access.

Aavash on MLRC as a research centre —

The Federick H Gaige’s book captures almost every nuance of Madhesh — politics, economy and its [over 70%] contribution to Nepal’s then GDP, language and culture, among others. While there are books on revolutions of Madhesh, Gaige’s book is so far the only well-researched account of the region. Similarly, no other research organisation prioritises Madhesh and its contexts although a few topics garner their latent attention.

We envision studying every aspect of Madhesh. We have just started and plan to reach there, coordinating with researchers. But before that, institutionalising the library is top priority.

Anshu adds on MLRC as research centre —

When we have built our capacity and can access resources, we will do that. The base for research is the library. I am sure youths who have joined us and will join us in the future will develop the capacity. We will hire the resources that need to be. Moreover, research cannot be carried out merely as a subject of interest. It demands a big amount of money too. We do not have financial resources — even for paying rents for the library shutter. Library members contribute from their pockets. So no immediate plans but we certainly have a vision.

Aavash on hopeless and frustrated Gen-Y of Madhesh —

We should be able to light hopes for the Generation-Y or millennial, who grew hopeless after the third Madhesh Aandolan failed. The feeling of defeat, being cheated by their own leaders and mentality of being weak against the state apparatus persisted in them.

Most of this generation, involved in all the rights and dignity demanding movements [Madhesh Aandolan first to third], were not much knowledge-informed but emotionally-charged. They know that Upendra Yadav went from a revolutionary to becoming power-bound. But the state never let them know that there were Madheshi leaders like Ram Raja Prasad Singh whose 4,000 bighas of land were nationalised during Panchayat and who rejected the post of prime minister, saying ‘I’m not for sale’.

By reading our history and drawing examples from highs and lows in international rights and dignity movements through our discourse, we can revive their hope.

Aavash on unaware Gen-Z and Gen-Alpha of Madhesh —

These generations have not faced discrimination in explicit forms following Madhesh revolutions, though discrimination now lies in terms of representation at decision making roles.

As they grew, the constitution was promulgated and the state was restructured into three tiers, with governance powers in provinces (Madhesh Pradesh) and local levels. This made them feel that the state has granted them the rights and the constitution does not discriminate, developing a soft corner for the state affairs.

However, the NPL racism incident made them realise that discrimination still prevails. To put into symbol, they saw Madheshis were humiliated even after carrying Nepali flag [and supporting and celebrating overall Nepal cricket].

Now, it’s our responsibility to make them aware of discrimination by connecting the NPL racism episode with historical discriminatory events and policies. We even have to scrutinise constitutional provisions that still perpetuate discrimination. And MLRC can be the right place for debates.

For instance, the constitution guarantees proportional representation. While Article 42 provides for ‘proportional representation and inclusivity’ of all communities in all organs of the state, Nepal Army implements the provision limiting itself to only ‘inclusivity’. Isn’t the Army one of the state organs?

By bringing up such contradictory provisions through discussion among youths, we can tell them that rights are yet to be guaranteed. In addition, we should read about the politics and movements related to [social] dignity from around the world.

Aavash breaks down what rights are yet to be guaranteed —

Everybody knows what they need to make their life dignified. They may not revolt, but they know. For instance, our grandmothers could not revolt but had the conscience that their husbands would sell homegrown paddy without consultation and that they were being whimsical. In short, everything that you need to live a dignified life is rights.

Beginning with the learning about the library and research centre, we stumble upon a notion — ‘जति यो देश तिम्रो, त्यति मेरो पनि’.

Anshu argues that the onus of proving nationality and loyalty to the country through this particular sentence always lies on Madheshis. “While there’s a large group who never had to assert this sentence. The day we (Madheshis) do not have to say it will be the day of assurance that we reached equal status.”

Aavash hopes unifying Madhesh region, which is scattered into various provinces, on emotional level through MLRC. “Youths from eastern Madhesh (in Biratnagar and Rangeli) and western Madhesh (in Bhairahawa) also sacrificed their lives for Madhesh polity,” he recalls.

And the conversation goes about cultural nationalism and civic nationalism, and understanding the state as a functional institution, with which we have signed contracts and delegated governance related rights to in the form of citizenship for political, social and economic guarantees and securities.

Read More Stories

Kathmandu’s decay: From glorious past to ominous future

Kathmandu: The legend and the legacy Legend about Kathmandus evolution holds that the...

Kathmandu - A crumbling valley!

Valleys and cities should be young, vibrant, inspiring and full of hopes with...

Understanding federal grants in fiscal federalism

Local budgets are where democracy meets the daily lives of citizensthis is a...