specialty coffee | export market | pro-poor intervention | climate change | private sector

A morning brew. A way of life. A shot of kick. A social lubricant. Over $40 billion in global cross-border exports value, and growing. A transforming global trend that rewards quality over quantity.

These characteristics best define a drink the world is smitten by since historic times – coffee.

Legend has it – Kaldi – a goat herder – discovered a coffee plant in the region of Kaffa in Ethiopia in the 9th century. The practice of drinking coffee however can be traced back to the 15th century in Yemen, but plants are believed to have been imported from Ethiopia, which today is one of the major coffee producers after the heavyweights like Brazil, Vietnam, Colombia and Indonesia.

Coffee then spread to different parts of the world and to different cultures – from Africa to the Arabian Peninsula and Middle East, and then to Europe and America – before reaching the height of perfection.

In between, coffeehouses thrived in parts of the world where coffee started becoming a social lubricant, mainly Europe, driving social interactions. The vibrant coffee culture also drove the demand for the beans, making coffee one of the lucrative export crops before the 18th century concluded.

The coffee trend then saw different waves, each marked by disruptive changes:

First Wave (1,800s): Growth in coffee consumption driven by mass marketing. Consumers were drawn to low price and convenience over taste and quality, but the era was innovative in processing, packaging and marketing. Rise of instant coffee like Folgers, Maxwell House, Nescafe.

Second Wave (1970s): Taste and quality became important. Emergence of coffee lovers’ interest in bean’s origin, processing techniques and roasting styles, but rise of large chains (Starbucks), and coffee shop experience took over. Emergence of Espresso, French Press and Latte.

Third Wave (2000s): Coffee, in its entirety, as a product and as a craft, takes centre stage with focus on the origin of the beans, processing techniques and roasting and brewing style. Emphasis on high quality. Rise of independent coffee shops, and specialty coffee.

Evolution of Coffee in Nepal

Coffee made its way to Nepal rather late in the thirties, and remained latent for decades until the eighties when growing interest of farmers from a few parts of the country were responded with the initiation of institutional and policy frameworks.

Many studies and reports recount a similar version – a hermit named Mr. Hira Giri planted the first coffee seeds in 1938 in the Aapchaur of Gulmi District, bringing the seeds from the Sindhu Province of Myanmar (then Burma).

Yet, until the 1970s, coffee failed to draw appeal.

In the late 1970s, the Nepal government began distributing seeds imported from India to smallholder farmers in potential districts through Agriculture Development Bank, which can be considered as first-time recognition of coffee as a potential cash crop.

In the eighties, coffee started gaining commercial momentum although the early years also saw coffee plantations as a means to prevent soil erosion, for instance, Tinau Watershed Project (1982) that promoted plantation of coffee on terrace risers.

Processing coffee began in 1983 with the establishment of Nepal Coffee Company (NeCCo) in Manigram, Rupandehi that processed dry cherries collected from farmers.

In Gulmi where the first seeds were believed to have been planted, initiatives were swift. In 1981, Gulmi-based farmers established country’s first coffee nursery while a Coffee Development Center was established in Aapchaur in 1984.

In Palpa, farmers organised to form the Coffee Producers Group in 1990.

A formal institutional structure – National Tea and Coffee Development Board (NTCDB) – was finally set up in 1993 with a view to lead initiatives for the development of the coffee sector.

A year later, Nepal made its first coffee export shipping dry processed green beans to Japan. That fiscal year (1994/95), Nepal produced coffee equivalent to 12.95 tonnes.

In 1998, Nepal Coffee Producers Association (NCPA) – the national-level association of coffee farmers groups, business people and cooperatives – was formed, which now has over 1,900 members.

Still, coffee hadn’t fully emerged as a cash crop.

For a tea-loving nation, evolving into the bitter taste of coffee took time which meant low domestic demand. Limited export capacity and lack of income-generating and technical knowledge further held back coffee’s potential.

Among the noted coffee outlets of present time, Himalayan Java Coffee started as the first specialty coffee shop in Nepal back in 1999/2000 when coffee culture was still non-existent. But gradually expanding tourism post-1990 was simultaneously setting the scene for coffee habits.

Farmers, mainly mid-hill, started recognising coffee as a high-value crop post-2002, seeing growing exports combined with increasing domestic consumption. Globally, it was the early years of coffee’s third wave.

In 2001/02, coffee production reached a triple figure for the first time registering coffee output of 139.2 tonnes.

These developments led to the introduction of Nepal’s first coffee policy in 2004. Organic certification started a year later, and ‘Nepal Coffee’ logo was registered in the Department of Industry in 2010.

The collective trademark ‘Nepal Coffee’ is so far registered in the EU and across seven more markets (South Korea, Singapore, Japan, Norway, Switzerland, New Zealand and Hong Kong).

The branding move was introduced to establish Nepal coffee brand in the global market, discourage the export of inferior coffee and gain competitive advantage and market opportunities.

In 2014, a Coffee Research Center was established in Baletaksar, Gulmi after the outbreak of Seto Gabaro (commonly known as Coffee White Stem Borer) – a type of insect pest that decimates coffee crops – intensified.

Finally, coffee was recognised as one of the potential export sectors in what was Nepal’s third generation trade strategy – Nepal Trade Integration Strategy (NTIS 2016) – but missed out in its priority list – so no action plans were designed for the coffee sector.

But as the global market experienced changes with shifts in consumer preferences in terms of quality, taste and varieties, especially towards specialty coffee, Nepal’s potential to cater to a niche segment that loves specialty coffee also started becoming more evident.

Nepali coffee is exclusively Arabica variety and further qualifies as a specialty coffee in specific markets for its distinct aroma, production outside the traditional tropical zone in the highlands, community-based production and organic content. Arabica variety accounts for 70% of the global coffee trade.

A five-year National Sector Export Strategy (NSES 2017) was then designed with the technical support from International Trade Centre (ITC), which aimed at increasing production of quality coffee cherries, developing support capacities for cooperatives to improve green bean quality and developing and promoting organic certification and establishing a certification process.

Present time coffee boom

Sleek independent cafes. Coffee haunts with roasters at their premises, and open libraries. Fancy eateries with inviting décor to small eateries. Shared workspaces. Small and big digital firms to traditional businesses.

Coffee is today served everywhere across Nepal’s cities, while coffee drinkers gather outside home and workspace along with their favourite cups, further driving coffee culture and coffee habits.

Growing coffee imports corroborate that coffee consumption is trending, and that it holds a promising domestic market.

Almost 280 tonnes of coffee was imported in the FY 2021/22, a 40% growth in import compared to the previous fiscal year. Further, the domestic market consumes over 70% of the national production, says NTCDB.

The demand is met by farming that has expanded to 44 districts, and across 31,340 small farmers. Among them, Kavrepalanchowk, Gulmi, Nuwakot, Sindhupalchowk, Kaski, Palpa, Ilam, Lalitpur, Syangja and Parbat were the leading ten producers in the FY 2020/21 contributing to almost two-third of the national production.

Navigate the Google Map below to understand the district-wise geopgraphical coverage of coffee production (In MT), plantation area (In Ha) and Number of Farmers engaged:

Whereas in a bid to expand production capacity of other districts and enhance production, Arghakhanchi, Gulmi, Syanga, Palpa and Pyuthan are enlisted in Coffee Superzone under the Prime Minister Agriculture Modernization Project (PMAMP).

Budding private sector interest

The idea of serving Nepali highland coffee beans to domestic and foreign markets has found strong reception from established and new entrepreneurs leading to rise in Nepali coffee brands, cafes, and suppliers.

Himalayan Java, that sources its coffee from Ilam, runs 23 outlets across Nepal including Jomsom and Namche Bazaar and even has footprints in the US and Canada.

Plantec Coffee Estate that produces Arabica coffee of Cattura variety runs a 1,100-ropani coffee estate in Nuwakot with annual production capacity of over 60 tonnes of coffee. Plantec sells its coffee under the brand name of Jalpa, among other brand names.

Producers like Nepal Organic Coffee Products, Alpine, Lekali, Lumle and Kar.ma, among other prominent producers, are also expanding markets in Nepal and abroad.

Entrepreneurs are also rolling up their sleeves to gain international recognition to seize international market opportunities.

In 2016, Greenland Organic Farm earned specialty certification from Specialty Coffee Association of America.

Two years later, coffee produced by Lekali Coffee Estate received similar recognition becoming the first Nepali brand to be reviewed by the Californian trade publication ‘Coffee Review’, one of the leading coffee guides in the world. Grown at Bhirkune Village in Nuwakot, the beans scored 90 points out of 100. In 2020, its coffee rated 92 points, one of the best in South Asia.

Dedicated barista institutions, along with hospitality colleges, are also growing in the cities, catering to the rising demand for skilled baristas, all thanks to growing local demand for skilled workforce and aspirations for jobs abroad where the coffee skills can prove handy.

A new and a strong avenue for export earnings, but miniscule production

Although a small player in the world coffee market, Nepal’s mountain-based green bean is a high price, niche market product, which presents a new but a substantial avenue for export earnings. Some even analyse that Nepal can become a regional heavyweight in specialty coffee.

According to NSES 2017, there is a growing allure of speciality Nepal’s coffee among specialty traders and roasters in North America, Australia, the Middle East and East Asia.

In 2020, despite the pandemic, Sindhupalchowk that promotes its coffee as ‘Sindhu Organic Coffee’ in foreign and domestic markets, exported around one-third (7 tonnes) of their 24 tonnes output to Australia, Japan and South Korea.

Compared to the first time coffee was exported, the country has since registered a significant increase in the overall coffee exports (see table below). However, in recent times, exports have dipped.

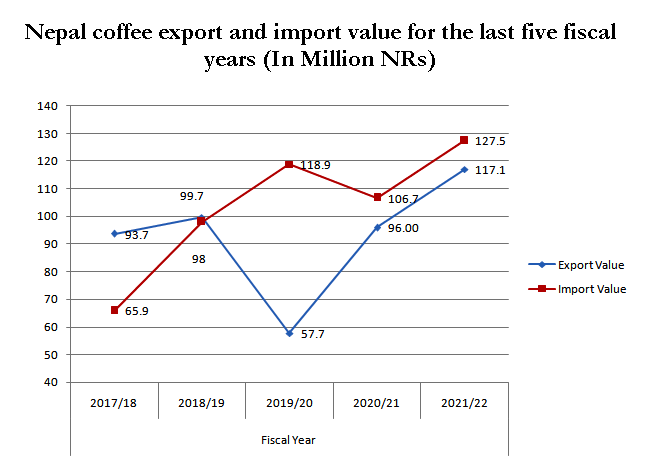

Coffee exports reached 84.2 tonnes in the FY 2017/18, dropping considerably to 69.5 tonnes in 2021/22 (See Graph 2). Exports value however increased to Rs 117.1 million in FY 2021/22 from Rs 93.7 million in 2017/18 (See Graph 3).

Germany, Japan, Switzerland, Netherlands and Australia were the leading exports market for Nepal in the FY 2020/21, contributing to around 90% of the total coffee export earnings.

Yet, overall export level is too tiny compared to a supposed combined demand for 8,000 tonnes of Nepali green beans in domestic and international markets.

The low export capacity is mainly explained by limited production volume and low productivity.

In the FY 2021/22, production was 355 tonnes compared to 523 tonnes in the FY 2011/12; despite an increment in the total plantation area to 3,343 ha land from 1,760 ha land.

Inadequate push: Challenges in the coffee value chain

Considering the five-year strategy, budding private sector enthusiasm, and global and domestic market surge for the Nepali coffee, and relative increase in coffee plantation land area, Nepal’s coffee sector is clearly underperforming.

In the coffee value chain, the sector faces numerous challenges resulting in low productivity, low production and even poor quality.

Presently, coffee cultivation is marked by sporadic production with farming done at small-sized lands that creates problems in quality control, coffee collection and prices.

According to Commercial Coffee Survey 2017/18 (2075/76), 16% of the coffee farmers cultivate coffees at less than a ropani land area while 71% farm at farm area spread at 1-5 ropani land area.

To increase production level, more plantations are needed which would require more land parcels. A research shows that a total of about 1.19 million ha area is suitable for coffee cultivation in Nepal, of which 5% is ‘highly relevant’ and around 34% is ‘appropriate’ while the rest of the area is ‘moderately suitable’.

In contrast, coffee cultivation is presently limited to 3,300 ha land.

For this, the government needs to unlock access to underutilised lands for commercial coffee plantations. One way to bring more land parcels into coffee cultivation is by introducing land leasing policy for foreign companies in the farm sector which would help attract foreign investment.

For producers of Arabica varieties, foreign investment can help in upgrading value-addition and product innovation (for example, specialty coffee). Inflow of foreign investment in Rwanda’s coffee sector is a useful case in hand. Allowing these investments, however, must consider the chances of asymmetric income sharing among the value chain actors.

Second explanation for low productivity and low production level is farmers’ knowledge gap and reliance on traditional farming tools and techniques for the crop that is sophisticated to grow.

Farmers face a knowledge gap on improved and organic ways of plantation, orchard management, sanitation and harvesting, which means that training farmers should sit at the top of coffee development strategy.

For instance, farmers tend to sell immature beans without grading and standard postharvest practices. These bad practices at the farm level affect the final quality of the coffee.

Unlike dominant producers of coffee in the world, Nepal’s coffee sector is far below in terms of mechanisation. Farmers still rely on traditional tools and techniques for grading, sorting and processing.

But farmers have little choice as modern alternatives are costly.

Farmers, including coffee processors, lack access to i) proper, appropriate or standard washing and size grading machines for cherries before pulping ii) appropriate pulping machines and iii) proper parchment drying systems or techniques, and iv) appropriate mechanical process for sorting, hulling and size grading of parchments v) mechanical devices to measure the moisture content of coffee beans.

In addition, there is inadequate postharvest handling including storage, transportation, packing and packaging, and the problem of lack of modern and economic irrigation systems.

Pest and disease, on the other hand, is believed to destroy around 20% of Nepal’s coffee plants annually. Coffee leaf rust disease (sindure rog) and Seto Gabaro are some of the recurring challenges to coffee plantations, which leave farmers with little choice – either destroy or replant.

Coffee sector is also constrained by poor research backup. Identifying right plant varieties that best suits different geographical and agro-climatic conditions of coffee districts and managing pests and diseases would require robust coffee research centres. Only one research programme (CRC) exists initiated by NARC in Gulmi.

Policy reforms and more government support and spending targeted at small-holder farmers, cooperatives and private sector commercial plantations are therefore critical to tap the huge export potential.

But coffee can also be a pro-poor intervention, as suggested by evidence from Uganda and Ethiopia.

Government spending and policies must focus on small-holder farmers, who have limited landholding and can’t invest in improving their farms and equipment, to enhance coffee yield and quality.

Farmers also need knowhow on managing/hedging price risks, and linkages with logistics and international buyers.

Apart from low production level, organic certification and quarantine requirements pose serious challenges to export.

International buyers mandate strict quality standards – from picking and grading to roasting and packaging – that underline the quality of coffee. Some coffee cooperatives and distributors have obtained organic certification but their international acceptance is limited.

Widely acceptable certification is expensive and difficult to obtain while there is a lack of accredited standard labs for product testing and certification.

Similarly, international quarantine agencies like Australian Quarantine Inspection Services (AQIS) do not recognise quarantine certificates issued by the Nepal Quarantine authority, compelling Nepali traders to opt for foreign agencies.

Climate change threatens coffee production

While Nepal’s relationship with coffee is getting relatively stronger, climate change has stark implications for the future of coffee and farmers worldwide.

First, a large number of small-holder farmers will be pushed into poverty due to erratic rainfall patterns, more frequent droughts and floods, and more pests and diseases. It is estimated over 25 million farmers are engaged in the coffee production worldwide, most of whom are small farmers.

Second, half of the world’s best coffee producing land could be lost to climate change effects, mainly increasing mean annual temperatures, reveals a study. Some of the world’s largest coffee producers will see a drastic decline in their land suitability – Brazil (-78.6%), Vietnam (-71.3%) and Colombia (-67.5%) – by 2050.

Few regions and countries, however, are expected to profit from climate change (e.g. Southern Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina, Chile, USA, East Africa, South Africa, China, India, New Zealand) due to increasing minimum temperatures of the coldest month.

A similar study at Kunming University in 2016 showed that Nepal could lose 72% of its suitable land for coffee by 2050 under different emission scenarios. The study suggests intercropping with bananas can provide needed shade for coffee bushes, a successful model in Uganda and Costa Rica that has benefitted smallholder farmers.

Read More Stories

Kathmandu’s decay: From glorious past to ominous future

Kathmandu: The legend and the legacy Legend about Kathmandus evolution holds that the...

Kathmandu - A crumbling valley!

Valleys and cities should be young, vibrant, inspiring and full of hopes with...

As of 27th May, Nepals capital expenditure stands at nearly 37%with one and...