Gender Equity | Banking | Gender Audit | Women in Leadership | GENDER POLICY

WOMEN OCCUPY ALMOST 40% OF THE WORKFORCE in the commercial (A-class) banking sector, but our research reveals the grim realities of women having a hard time breaking the glass ceiling. Women are in a vicious circle of familial, social, and institutional constraints that are perpetuated especially because they do not have women leadership in the first place for their problems to be visible.

Out of 28 CEOs and 26 DCEOs from 28 banks (27 A-class commercial banks and Nepal Infrastructure Bank), only four are women. It was only in April 2018, Anupama Khunjeli was appointed the CEO of Mega Bank, becoming the first woman in Nepal to lead an “A-class” commercial bank. She resigned in 2022. The incumbent acting CEO position is now held by Raveena Desraj Shrestha. Even in the central banking with over six decades of history, only one woman has made it as far as deputy governor, which was a year ago when Dr. Nilam Dhungana Timsina assumed the rank.

The bigger picture is far from being inclusive. Our work shows women account for only nine percent of the executive positions (C-suite positions) — 18 out of 201 positions. Out of the 155 provincial heads, only six are women, accounting for only four percent. Many other factors also contribute to this disparity.

One of our respondents, Sabina, a Kathmandu-based manager in one of the commercial banks, shares some of her experiences about both subtle and blatant sexism that prevail in her workplace.

Sabina expresses that dealing with a male-dominated client base is demoralizing because they show obvious discomfort while dealing with a woman manager. "Some clients presume women managers to be incompetent solely based on their gender," she says.

Sabina also shares how men and women are held to different standards at home because women are expected to take a leave during home rituals, while not doing so brings about accusations of not being "capable" to balance the work-life equation.

But choosing to work late or during rituals also is not easy for women. Sabina shares that apart from the family, even colleagues pass remarks such as, "Why are you working so late?" or "Don't you need to give time for your babies or home?"

Sabina explains, "It is these microaggressions that deter women from taking bigger roles and responsibilities." "Not all women are thick-skinned; they come from various parenting, childhood, and education backgrounds that play a big role in conditioning women into adjusting rather than taking their stand."

Our other respondent Pushpa, a branch manager with over 10 years of banking experience, echoes Sabina. “Banking is a demanding sector where women deliberately become comfortable in not climbing the ladder because bigger positions require women to be heavily overworked at work and at home. They just do not have time, and managing all that time will burn them out.”

Pushpa adds, "In the banking industry, switching job place within the industry ensures a certain growth but women do not have time to seek, apply or network for newer opportunities." Pushpa finds that a lot of the women are happy where they are in their careers after reaching a certain level of stability.

We also examined the proportion of women in leadership roles within the 18 ‘B’ class commercial banks.

Out of 33 CEOs and DCEOs, none are women. Only 13 women (12%) are in the boardroom of 106 members. In total of 229 leadership positions (including CEOs, DCEOs, senior management and departments, regional and unit heads and in charges), women lead 21 of them which is just nine percent.

Proportion of women in charge at mid-level positions

Our research also broke down the gender diversity at mid-level managerial positions but stats aren't impressive.

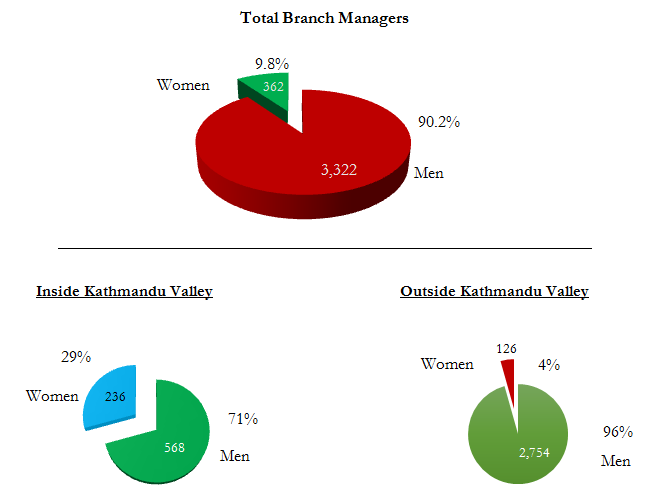

Out of a total of 3,322 branch managers, 11% are women. While Kathmandu valley sees a higher rate of women as branch managers at 29% or 236 in a total of 804 branches, the number significantly reduces to 4.37% in branches outside the valley (126 out of 2,880 branch managers), our data shows.

Interestingly, the number of women leading bank departments or units is relatively higher though still small. Out of 483 departments, women presently lead 99 (20%) of them.

Fewer women in these positions that are considered gateways to higher leadership roles mean that only a few of them will climb up, perpetuating the gap at the top. The gap also means that there will be fewer women role models for the present and aspiring women bankers for a foreseeable future.

Our respondent Pushpa also shares, “At managerial levels, training opportunities are equally distributed." "But since few women make it to the executive level, usually men get access to better opportunities while also benefiting from career growth by leveraging their male-dominated networks."

That’s not all. Another respondent, Rohini, a senior assistant at a Kathmandu-based branch, shares that women have to dwell over adjusting their pregnancies so that it doesn’t affect their appraisal or promotion.

"Not only does this take a psychological toll on women, but it also has the effect of fizzling out their career ambitions and they choose to remain as a secondary income earner in their family," she says. "I completely understand their choice because they cannot commit to bigger responsibilities or even exposure opportunities outside the valley or their hometown due to familial constraints, and even a lack of sense of security, but it is sad."

Men do not only benefit from exposure opportunities and the liberty to completely focus on their jobs only but also dominate the existing spaces. "Industry events are mostly male-friendly and male-dominated," says Sonam, who has been in the banking sector for over 14 years and presently heads a department.

Sonam believes that introducing women-centric policies and investing in the women-workforce shall bring dramatic progress in the status of women in the industry.

According to Rohini, "It is time that the HR recognised their potential and not limit them to frontline work only because women are more than just ‘mitho-bolne’. They must realise more women will join the banking sector in the future."

We found out that in 28 banks, only 28 women have made it to the boardrooms out of 179 board members — that’s 15.64%. Out of the total 28 boardrooms, only one is chaired by a woman — Zarin Daruwala at Standard Chartered Bank (SCB) Nepal — who also serves as the CEO at SCB, India.

Civil Bank, Global IME, Himalayan Bank, and NMB — don’t have any women in their boardroom yet although the Company Act for public companies mandates at least one woman in their boardroom.

Sonam believes that appointment of women as board members is just a formality but banks are doing a considerable job at developing women's soft skills, but there is still so much to do.

What must banks do?

"There is no pay gap in the banking sector but there is a huge opportunity gap," Sonam adds. "Banks must chart out a vision to achieve a certain level of women leadership within certain years and push the agenda strictly — this is how many women leaders we will have five years down the line. Otherwise, the gap will persist."

Sonam further observes that it is easier for men to get a good appraisal by being friendly with their bosses/supervisors but for women, it is difficult as their own peers start saying malicious things. "Unlike men, women are negatively judged when they share a strong professional relationship with their supervisors although that’s what the job demands."

Our respondents offer similar solutions to the existing barriers for women in the industry. Moving forward, Rohini wants to see banks with a vision for getting more women in leadership roles. "For example, banks should set a ‘target number of women in leadership within specific years’ in order to bridge the gap between men and women in leadership positions."

Similarly, Sabina suggests, "Offices should conduct gender audits and put in policies that are women-friendly and support women to climb the corporate ladder." "It would be a great support if men and women are gender-sensitive at workplace and men are supportive at home."

Some of these solutions can be extended paternity leaves; child day-care facilities; pick-up and drop during pregnancy; hybrid work models, with flexibility and remote work options; women-friendly workspaces; improved work culture; secured office quarters during out-of-home transfers and more professional courses and mentoring, networking and sponsorship opportunities, our respondents suggest.

Pushpa adds, "Managers must acknowledge the fact that women are equally productive and efficient and must consider the constraints they face in their daily lives when evaluating performances." "Performance evaluation should be fair and free of biases, based on actual performance and not based on time spent at workspaces," she adds.

Banks can and must lead the way in filling the gender gap at the top

Banks have shown tremendous business growth and enhanced their capabilities in multiple fronts in the last two decades. They clearly possess the resources and capabilities to identify the conditions that can help more women advance into leadership roles and to plan a clear route of progression for them. But first, they must have the intent similar to how they would have approached banking digitisation.

Getting more women into leadership roles also makes a strong business case. The conspicuous gender gap in the industry and lack of intentional effort to get more women into senior leadership will only deter present and aspiring female bankers, which may lead to a talent gap in the near future, and even workforce shortage.

___________________________________

Notes:

Read More Stories

Kathmandu’s decay: From glorious past to ominous future

Kathmandu: The legend and the legacy Legend about Kathmandus evolution holds that the...

Kathmandu - A crumbling valley!

Valleys and cities should be young, vibrant, inspiring and full of hopes with...

Israel attacks Iran’s nuclear and military sites, Iran retaliates with drones

In a latest escalation in West Asia, Israel targeted nuclear and missile facilities...