STARTUPS | ENTREPRENEURSHIP | ECOSYSTEM | URBANTECH | Innovation

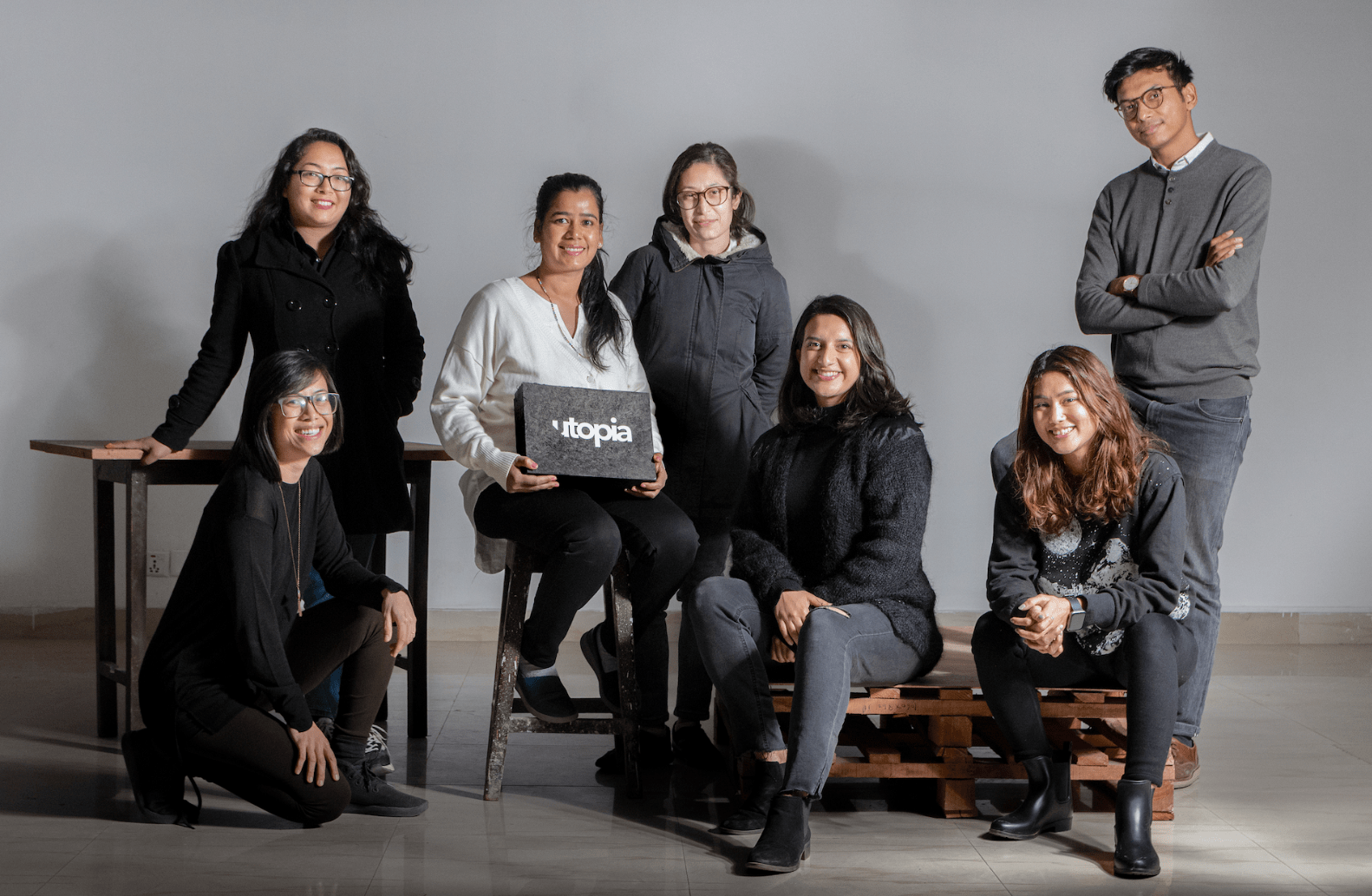

Arriving at a large commercial building in Teku, I climbed four long flights of stairs plastered with posters of Goddess Lakshmi to the workspace of ‘Utopia’. Unfamiliar with start-up jargon, like ‘urban tech’ and ‘emergent blueprint’, and new to the world of innovation hubs, entrepreneurial ecosystems and accelerators, I was unsure of what to expect.

But as my conversation with Dori progressed, I got a peek into the stimulating world of problem-solving. Of puzzling the pieces of society matching the excess to the gaps. Of charting the future of a city by connecting the dots making clever routes and maps. Of asking the right questions to the right people and watching and supporting as ideas are diligently transformed into reality. Of the value of being the “living room for anyone that cares about the future of this city.”

Utopia is a product of an ambitious imagination but their grounded approach to providing a supportive ecosystem for entrepreneurship provides a strong foundation for such high reaching aspirations. Dori jokes, “We call ourselves Utopia for a reason, we don’t shy away from big ideas.”

The philosophical complexity of Utopia’s vision does not cloud the simplicity when put to action, and this precise combination led to this truly insightful conversation.

What is Utopia?

Our mission is to co-build a thriving urban innovation ecosystem in emergent cities across Asia, Africa and Latin America through a network of urban venture studios. We work with entrepreneurs in creating urban solutions that address the pressing needs of today, with an eye on the future.

In the process of ideating and co-building, we take a long game approach. Our commitment is both for within our own lifetimes (50 years in the future) and beyond. When we say this, we’re looking at 100 years in the future and trying to answer the question — what can our cities look like?

Utopia’s urban startup studios are called CITYLABS, which are platforms for urban innovation, currently active in Lagos, Rio de Janeiro, Manila and Kathmandu. Here, entrepreneurs collaborate with Utopia to build and grow urban tech startups.

What is CITYLAB?

For the current cohort, the focus of Kathmandu CITYLAB’s entrepreneurs-in-residence program is urban climate technology. For the first three months, we provide a select cohort of entrepreneurs with tools, resources and processes and co-develop a prototype and shape a business model. After three months, we have a moment we call “gateway moment” where the Venture Committee chooses entrepreneurs and ideas that demonstrate the most potential for traction.

Then, we co-build that idea with the chosen entrepreneurs for the following 6-15 months. It's a difficult road ahead for entrepreneurs in an emerging market focusing on urban issues. But, there are many issues that need solutioning.

The CITYLAB is a long term process, you may be a part of a cohort for a short time, but you become a part of the community forever. It's important to have a space people can come in anytime. It's an open door — a living room for anyone who cares about the future of the city.

In Kathmandu, there are a few investment operators (impact investment, private equity and venture capital (VC) funds). The larger investors (who are mainly development funded) have a limited pipeline. Accelerators mainly work with already registered companies. We saw an opportunity to co-create innovation and connect innovators and entrepreneurs with urban issues. Essentially that’s what we do — bring together the problem, solution and capital.

When it comes to startups, we focus on the problem domain. As one of our Utopia partners would say, “we’re married to the outcome”. We look at what the city could become and sometimes work backwards, or take a step back, and see how we can get there.

Give us an example of an “urban solution” that Utopia has played a role in innovating?

One venture we are co-building is called ZERO.

At ZERO, our mission is to (re)introduce circularity to our consumption habits through regenerative products that eliminate material waste. The first step is to create awareness and demand (simultaneously as laws catch up), while the ultimate goal is to lower the consumption of petroleum-based, single-life products.

The idea is to first meet local demands, and eventually scale up to global markets.

Alongside, we will create a loop. Simply adding bio-plastics into use and waste streams does not mean everyone will know how to work with them. People will have to know the difference between normal petrol plastics and bioplastics, but how?

Behaviourally, people are used to putting plastic in a bin. If bioplastics aren’t disposed of correctly, the technology is not as effective. And not everyone has the capacity to dispose of waste in the most efficient way (in the case of bioplastics, that would be home or industrial composting) due to increasing apartments and decreasing open land and few service providers.

So what are the workarounds to this? How do we enhance consumer understanding and introduce new innovations and simultaneously transform dysfunctional systems?

The intent here is to use circular economy principles around material use. How do we create consumption practices and systems that give materials long term use, support local ecosystems, are recyclable and can remain in the use loop, and easily be put back into nature? That's a big goal. But as you can see from our name, Utopia — we don’t shy away from big ideas.

How would you define “tech”?

The mainstream definition of tech, with the rise of Silicon Valley and its dominant business models, is “hi-tech” emphasising digitisation and advanced technologies like blockchain. But we see a lot of examples where we use simple and available technology.

A lot of what we try to do — it's not about reinventing the wheel. Perhaps when there are really sticky situations and that is the only way out, then that makes sense. But there is so much tech and innovation out there, the question we ask is — how might we leverage existing technology and innovation and contextualise it for use in emergent cities?

Actually, that's a lot of what innovation usually comes out of. Perhaps the tech has already been developed for a different market, context and use. Innovation is also about taking it out of that context and seeing how it might be applied to different situations and populations. Of course, you’ll have to tweak it. Those tweaks are where some of the interesting innovations come out. But, this doesn’t mean we use only existing tech; we also believe in and nurture locally grounded and sourced innovation.

What does a “decentralised” and “adaptive” city look like? How can these characteristics be a force of transformation, innovation and social good?

Decentralisation is quite a heavy term in Nepal, due to the recent transition into federalism. We are putting that aside, and thinking more about how increasing city demands for infrastructure, amenities and services can be met.

Often the centralised system entails little benefits due to factors such as physical location, and a handful of people making unilateral decisions for such a large, fluid and diverse population.

As you see, across any city, each area has different characteristics. Decentralisation is democratising the city to make it more liveable by creating a close-knit community, getting people who live there who understand their area, services and systems and getting them involved in how resources are distributed and what services are delivered.

In terms of adaptation — the current trends can change anytime. So how do we create systems for cities that are future-facing? The current trajectory is problematic and deeply embedded. We are yet to solve many problems like waste management and energy systems which are growing every day — and are influenced by economic, social, environmental and political conditions. So solutions must be future-facing rather than temporary relief.

In terms of physical form, modularity is important — products where you can easily replace different components. Modular thinking is also significant in non-physical forms. We don’t know what the world will look like in 100 years but we can imagine.

What different components make the product or service — and what are their trajectories? If it is physical — what is the source, and where will it end up? On the service side — what technologies will change in the future? What will the new forms of transport or fuel look like? There are many layers to innovative adaptability — not just in the product but also in the process behind the thinking of innovation.

The process of imagining the future cities and their moving pieces and parts, is that a part of the incubation process?

We always begin at the end; we start by imagining the outcomes — what kind of city do we want to inhabit in the future? We also think a lot about the process. At the macro-level thinking, it’s about the future, systems and institutional stakeholders.

For the incubation process, we have designed a program drawn from design thinking, systems practice, complexity theory and emergence theory. It may sound like throwing around a lot of buzzwords, but we draw from many practices/designs/approaches and theories to figure out the most sensible way to move forward in the present context. We constantly ask ourselves — what is relevant now in the urban tech space.

There are so many different approaches and methodologies now that they can fall through the cracks, but we take on the work of understanding different methodologies and filtering to find what makes sense before applying. We help entrepreneurs do this and find new ways of framing.

What is framing?

Certain perspectives and narratives about issues keep on repeating. People repeatedly talk about how bad the air quality is due to increasing vehicles or brick kilns. The narrative locks your curiosity and creativity, preventing you from analysing the deep roots of the problem or finding innovative solutions.

In terms of approaching problems, we find it helpful to oscillate between micro and macro, theory and ground reality, simplicity and complexity. There are times when you need to simplify in order to think of solutions. Other times, you get so zoomed out and theoretical that you need to get grounded. But if you’re too much into the details, you might forget the bigger picture. This oscillating is important to make sure you are focused on what is important while staying inspired.

What about the more technical aspects of company building?

Of course, there is the more traditional accelerator/incubator company building component — how will you make money? What is the mission and the focus? How can you move the needle and disrupt the sector? But in the early stages of the entrepreneur’s journey, we also focus on the human and our responsibility to society and to future generations as a part of this process.

This can change from one cohort to the next or one idea to the next. We build our process ourselves. We iterate and reiterate it all the time–every day! We depend on an amazing local, regional and global network of contributors — people from the future, regenerative design, tech, product design, and climate tech spaces. We pull them in as we need and they share their knowledge, expertise and guidance with the entrepreneurs. The focus in the first phase is to work with the entrepreneur to get to a prototype. The nitty-gritty of venture building is the second chapter.

How do you learn about the context of the cities you’re in? Do you conduct research?

We regularly tap into our ever-growing urban community informal to informal interactions - gaining insights into topical issues, venture building, emerging technology and collaborative opportunities.

Our research often results in the form of sticky notes. Actually, I could say our research takes the form of start-ups. That is how we understand what cohorts could be working on and where to nudge ideas and what the existing urban ‘problem spaces’ are.

For us it is not about traditional forms of literature review and research but about generating interest, increasing visibility and testing ideas around urban issues. As a platform, we organise events and try to bring all kinds of urban residents into the CITYLAB.

What are different assets that are underutilised or underappreciated in the context of Kathmandu when it comes to innovation?

A lot of knowledge and skill that evolved and fine-tuned over many generations in Kathmandu are lost over time, including the deterioration of much of the physical and non-physical infrastructures built by different native settlements and kingdoms. In physical form, we can see the transition between before the 2015 earthquake and today. There’s a tremendous loss.

While there is a resurgence of interest in indigenous knowledge, a generation has missed out on inheriting past knowledge their families had gained over generations because they are compelled to switch professions. People also had to leave their homes and villages. So, the knowledge spout dried up (just like Kathmandu’s Hitis). Still, there’s a lot that can be realised if we act quickly.

Also, there is a fostering of community in the Nepali culture. Altruism is deeply embedded too. In recent memory, emergency support poured out from the Nepali diaspora and local communities during the disaster.

A lot of the city is still not detached from this community sense, which is rare in many megacities around the world. It can definitely be leveraged.

What pressing issues need immediate solutioning in Kathmandu?

Catalysing existing knowledge and skills to contextualise systems brought on by modernisation.

Kathmandu is not a large city. It should have been easier to get around. Yet mobility is a pressing problem. The desire to own individual vehicles has led to encroachment of city spaces and soaked up physical, infrastructural and financial resources, leading back to increasing demand for vehicle ownership. Now cars and motorbikes take up most of the road space, others are compelled to manage with the remaining space.

Last-mile transport is another issue. Bus services are available but they don’t connect you to every destination - Safa tempos only partially help to fill this gap. Elsewhere, micro-mobility has been seen to help tackle this issue with the increasing electrification of scooters and cycles.

There are other pressing issues like food systems and open spaces as well.

At the policy level, what systems and structures create hurdles to innovation and entrepreneurship?

It’s unfortunate that digital technology is approached with blanket regulations rather than taking time and effort to understand the emerging technologies better and then develop appropriately contextualised regulations. A recent example is cryptocurrency.

Banning cryptocurrency can hinder innovation because it prevents us from leveraging its potential when the direction in commerce and finance is moving towards digitization. There are risks on both sides, but perhaps this is yet another opportunity for innovating within constraints.

Another example is drones. When drones were first introduced, they were highly regulated. While the security and privacy risks that arise with drone use are real, legislation was punitive and workarounds cumbersome – regardless of intent.

What are your thoughts on entrepreneurial culture in Kathmandu?

There is budding interest, but either the opacity of the entrepreneur’s journey or the glamorization of the most visible startups has led to a blurry understanding of what building a company requires. We’ve not seen many initiatives that attempt to demonstrate or clearly communicate the realistic needs and steps to early or aspiring entrepreneurs - we’re constantly iterating on this ourselves.

There aren’t many entrepreneurship support organisations (ESOs) in Kathmandu — workshops, seminars and classes do exist but programs with longevity are rare. In our experience, the first weeks or months of working with entrepreneurs may generate a lot of excitement. But when you part ways at this point, a lot of things happen — from distractions to deviations and resource crunch to getting stuck on a technical challenge.

Our approach is to provide a holistic support system for entrepreneurs that we work with. We don’t really see that here. Our allies are doing incredible work, but early (or pre-) stage support is minimal. There are some opportunities funded by development aid and emerging private equity funds later down the pipeline that exist as well but focus on connecting the ecosystem is lacking.

At Utopia, we hope that even if we don’t build a large number of companies, we will steadily strengthen the urban innovation ecosystem. We hope to share resources and tools and build mindsets for entrepreneurs to view themselves and the systems around them differently - as opportunities to disrupt - even if they later decide to build a company outside of the CITYLAB, or not to pursue entrepreneurship.

We believe there is a ripple effect when it comes to innovative thinking. We don’t only consider entrepreneurs that approach us with ideas; we are also interested in creating an “on-ramp” for non-traditional entrepreneurs. For example, those considered by the development world as SMEs have to conform to development models, which are usually debt-based financing, and to inflexible metrics. We are here to offer an alternative pathway, and create a bridge to the startup world for equally capable entrepreneurs with limited social/economic capital.

What role do tech solutions play in mitigating the circumstances that are at the root of the urban challenges/needs?

Tech is more of an enabler than a solution. We focus on the context from the start. We hone in on the problem deeply focusing on understanding the issue, the users and the context before heading for solutions. Even the solution or innovation is an opportunity to get more user feedback. The first 50-100 iterations of an idea may not be what you actually put out into the market.

When it comes to innovation, especially in tech– scalability is often a challenge. Could you tell us about some of the ways CITYLAB addresses this?

Scaling is a priority for us — one of the three essential filters that we apply at the early stage. We assess if the innovation can reach one million people, customers, or in monetary revenue (because different innovations might have different models).

We see if a Kathmandu-based solution is relevant and applicable in Dhaka (where we are hoping to launch within a year from now). But if the solution is easily adaptive, then we will ideally be able to tweak a few things and take it to a different location. Innovations should be lightweight, light touch and modular, able to be transplanted in parts to different contexts, especially amongst emerging cities.

This is just our hypothesis for now, and what we try to move towards. But our cities are also complex, and there may be circumstances that hinder ‘lightweight’ innovation. As I’ve mentioned before, all these complexities are opportunities to learn and realign for us!

Utopia solely focuses on emergent cities in Asia, Africa and Latin America – why these cities?

Cities are the arena to build the next era of civilization, and emergent cities across Asia, Africa and Latin America are where the majority world will live by 2100. These emergent cities also share similar characteristics and issues given the often resource-constrained growth happening across similar time horizons, though they may differ in variations and conditions.

Our hypothesis is that there is much more to learn across these cities than to learn from the hierarchical dynamics we see in development between Europe/USA and Africa or Europe/USA and Asia.

Our intention is for the CITYLABS across Asia, Africa, and Latin America to form a network of sister studios, and provide opportunities for scaling, cross-pollination and inspiration across cities. There is a lot of potential to collaborate and learn from entrepreneurship and ideas across these contexts. We have already had a couple of cross over sessions between Kathmandu and Manila, which was an exciting exchange.

There is so much innovation and ingenuity in emergent cities. It is an unfair assertion that they are “less inclined” towards innovation. Anything that any entrepreneur needs is about time, space and platform. A few nudges here and there – sharing methodology, developing frames, ways of thinking and schools of practice. It's about creating a platform to bring all these resources together and nourishing the people and ecosystem

We see cities as the arena to build the next era of civilization. Everything that's going to happen in the future will happen in cities first. The city itself is essentially a lab. How do we start to conceptualise and make real innovations that improve lives? Our goal is to help shift from this narrative of the city as an often unhealthy, disconnected, and destructive place, to one that fosters planet-forward and human connection and progress.

Read More Stories

Kathmandu’s decay: From glorious past to ominous future

Kathmandu: The legend and the legacy Legend about Kathmandus evolution holds that the...

Kathmandu - A crumbling valley!

Valleys and cities should be young, vibrant, inspiring and full of hopes with...

Consumer Court rulings spark nationwide doctors’ strike

Doctors across Nepal suspended all non-emergency medical services on Monday in protest against...