Nepal air quality | Life expectancy | Kathmandu Valley pollution | WHO air quality guidelines

Air pollution is the leading risk factor for death and disability in Nepal followed by malnutrition and tobacco, reducing life expectancy by 3.4 years, states the World Bank’s recent report ‘Towards clean Air in Nepal’, further adding that it causes 26,000 annual premature deaths.

The report warns that the country’s rising pollution level represents a key public health and economic crisis, with air pollution levels in the Kathmandu valley and Terai seven to eight times higher than the World Health Organisation (WHO) guideline for the past decade.

The key pollutant, Particulate Matter (PM) smaller than 2.5 microns (abbreviated PM2.5) penetrates deeply into the lungs and other vital organs, strongly contributing to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.

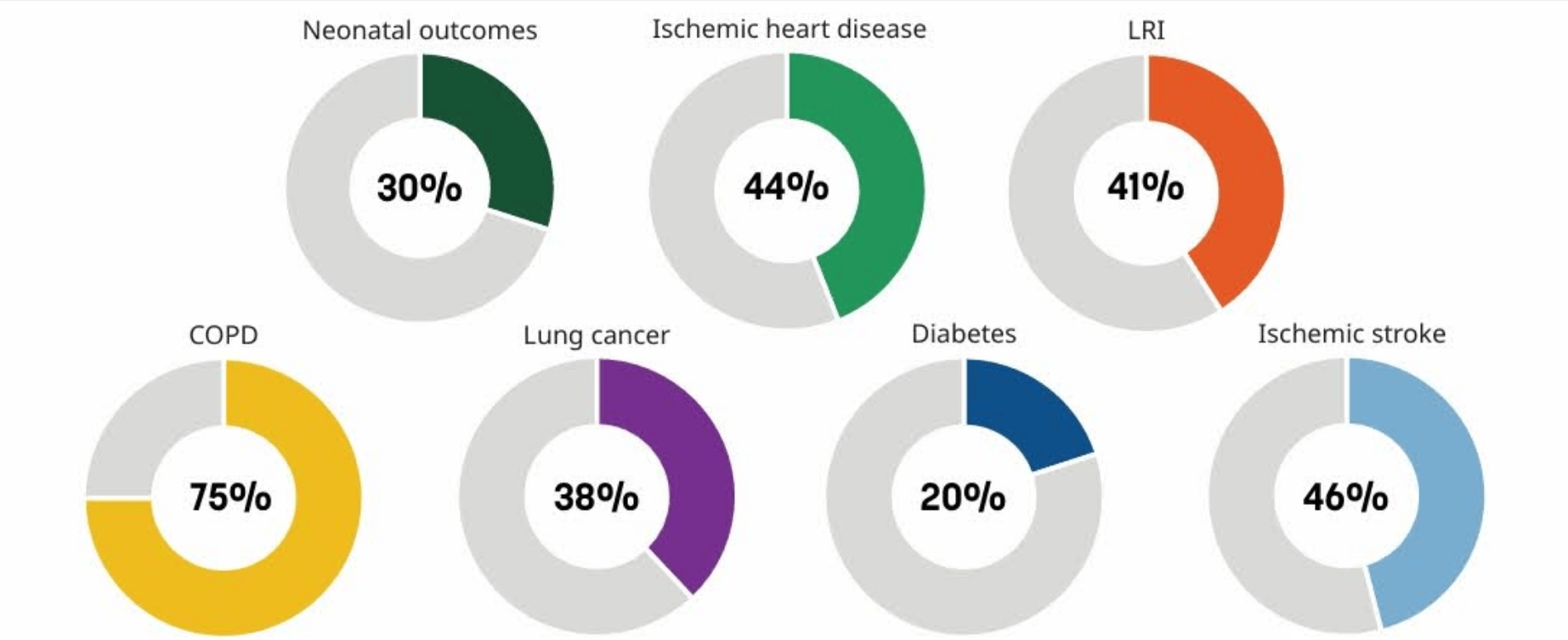

The Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 reflects the percentage of deaths due to air pollution as follows:

According to the report, poor air quality costs the country over six percent of its annual GDP by degrading human capital—the sum of people’s productivity, incurring significant financial costs for medical expenses, and impacts on the tourism industry and aviation sector.

In Kathmandu valley, the report identifies industrial production (mainly fuel-burning boilers), cooking, and transportation as major sectoral sources of pollution—trends expected to continue without stronger action.

The valley’s road dust accounts for 8% to 12% of total PM2.5 pollution, with brick kilns and forest fires as other key contributors. Solid fuel consumption contributes 25% to 40% to total PM2.5 exposure in the valley and Terai. About a quarter of the Valley’s pollution comes from outside the region, including international sources, with the valley's bowl-shaped topography trapping pollutants.

In the Terai, which has geographic proximity to high emission density areas in India, transboundary pollution is even more severe. Two-thirds of PM2.5 exposure comes from across borders, driven by emissions from agriculture and industry in neighbouring areas of the Indo-Gangetic Plain.

Transboundary pollution originates in one country but crosses a border through pathways of water or air. Transboundary air pollution in Nepal associates with the Indo-Gangetic Plain and Himalayan Foothills (IGP-HF) airshed in South Asia, including parts of Bangladesh, Bhutan, India and Pakistan.

If no concrete actions are undertaken, pollution will worsen by 2035, the report warns.

PM2.5 levels could rise to 52 µg/m³ in Kathmandu and 42 µg/m³ in Terai, well above the WHO's interim target of 35 µg/m³. Such pollution levels could cause tens of thousands of premature deaths—especially among children and the elderly—while straining healthcare and hurting economic productivity.

However, Kathmandu can meet the air quality goal with three cost-effective interventions: cleaner industrial boilers, electric or improved biomass cookstoves, and strict vehicle inspection and maintenance for heavy-duty vehicles, which are ranked by pollution-cutting potential and costs between $1–5 million per microgram improvement. These alone could bring PM2.5 levels down to 35 µg/m³.

However, writing for the_farsight, Udyan Devkota, a doctoral candidate at the Department of International Relations, South Asian University notes that, “air pollution remains out of priority for government authorities, while citizens have come to accept pollution as a part of their lives, reflecting a shared complacency on both sides.” He further writes, “In Nepal and countries across South Asia, air pollution has yet to spark public outrage and become a significant election issue despite being one of the leading causes of premature deaths.”

After decades of overlooking the crises, this year’s federal budget, however, has included some control measures for Kathmandu, which includes measures such as free land and concessional loans for electric boiler upgrades to incentivise industries to relocate outside the Valley. It also aims to improve vehicle emission monitoring using advanced technology. The budget has also stated it would introduce awareness campaigns to combat wildfires and a reward system for reporting and helping control fire incidents.

In the Terai region, however, local action isn't enough. Due to cross-border pollution, costly extra measures or regional cooperation will be essential. The report urges Nepal to prioritise collaboration through forums like the World Bank–ICIMOD dialogue.

As Udyan Devkota notes, air pollution in South Asia is inherently a regional crisis—and Nepal, positioned downwind, absorbs a disproportionate share of transboundary pollution. “It’s efforts, while necessary, would not be enough.”

The scale of the challenge is clear in the World Bank’s estimates—that reaching the 2035 target would cost around $6 million annually in the Kathmandu Valley through local measures. In contrast, for the Terai, achieving the same goal through local action alone would cost about half a billion dollars ($500 million) annually.

If Nepal were to reduce the particulate pollution, people in the mid and eastern Terai—home to nearly 40% of the population—could gain 4.8 years in life expectancy. In Kathmandu, residents would see a 2.6-year gain.

Read More Stories

Kathmandu’s decay: From glorious past to ominous future

Kathmandu: The legend and the legacy Legend about Kathmandus evolution holds that the...

Kathmandu - A crumbling valley!

Valleys and cities should be young, vibrant, inspiring and full of hopes with...

A week into Israel-Iran conflict

The latest escalation between Israel and Iran has entered its eighth day. Heres...