Starlink | SpaceX | Nepal Telecommunications Authority | Digital transformation | Satellite Internet

Paul Krugman, the 2008 Nobel Laureate in Economics, wrote in the Time Magazine in 1998, “The growth of the Internet will slow drastically, as the flaw in ‘Metcalfe’s law’—which states that the number of potential connections in a network is proportional to the square of the number of participants—becomes apparent: most people have nothing to say to each other! By 2005 or so, it will become clear that the Internet’s impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine’s.

A quote used frequently against him, which he has clarified was used in a different context: “the point was to be fun and provocative, not to engage in careful forecasting.”

Yet the internet that he critiqued, although and perhaps in different context as he clarified, has since become so vital that private companies are racing to space to expand the internet's global reach and performance—and countries are eager to adopt it. Considering Nepal’s rugged geography and poor broadband infrastructure, this satellite internet seems an ideal solution.

A recent notice by the Nepal Telecommunications Authority (NTA) regarding the unauthorised use of satellite internet services by some mountaineering companies in the country's northern parts, including base camps underscores this. Marked as a highly important notice, the agency warned of legal actions against violations, which includes a fine of a sum of NRs 500,000.

The incident highlights both digital disparity and a growing demand for reliable internet across the country. The Nepal Living Standard Survey 2021 shows 39.7% of Nepali households are using the internet. That however is fragmented, with urban areas outside Kathmandu Valley and rural areas facing digital gaps—43.2% of urban households outside Kathmandu Valley and only 17.4% of rural households outside the valley avail the internet service, respectively against almost 80% of the Kathmandu Valley urban households. According to the NTA, fixed broadband service’s density is just 42.2%—meaning only 42 out of every 100 households or businesses are subscribed to a fixed broadband connection.

Owing to its ability to reach anywhere in the world, Starlink, with its constellation of low-Earth orbit satellites is ideal for the kind of geography that characterises Nepal. But, despite high-level meetings in the past between Starlink top executives and the country’s political leadership for Starlink’s entry into the Himalayan nation, the globally expanding satellite internet service remains unavailable.

Starlink’s expanding reach

Operated by SpaceX, Musk announced Starlink in January 2015—now available in over 100 countries, including its launch in Congo last week.

In India, Starlink recently secured a Letter of Intent from its Department of Communications in compliance with the country’s stringent security guidelines, which includes storing user data within the country, enabling real-time location data/tracking of user terminals and a ban on connecting Indian users to terminals outside the country. The satellite ISP had already joined hands with two Indian telecom giants, Reliance Jio and Bharti Airtel, this March for distribution of its internet services. Starlink which debuted in South Asia through Sri Lanka is already operational in Bangladesh and Bhutan as well.

In Africa, the connectivity has reached 21 countries, with Congo, which earlier had banned Starlink for security reasons such as its potential use by rebel groups, becoming the latest country to join the network.

Starlink is yet to operate in South Africa, Africa’s largest economy—also the birthplace of Starlink founder and the world's richest person, Elon Musk. Operating in South Africa requires network and service licenses—each requiring a 30% ownership stake of its historically disadvantaged groups, mainly the Black population. Musk and South Africa are embroiled in a tussle over the provision, with Musk referring to the provision as ‘racist’ in his X post.

What’s going on with the Nepal entry?

Nepal also has been on Starlink’s radar for operations with its inclusion in SpaceX’s coverage map in 2023. SpaceX is the parent company of Starlink. That same year in June, SpaceX officials met then-Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal and government officials to explore Starlink’s possibility in Nepal.

This was followed by a meeting between Rebecca Slick Hunter, Global Licensing Head of Starlink, and the country’s communication and IT minister, Prithvi Subba Gurung.

Starlink then gave a presentation to PM Oli in October 2024, which followed a virtual meeting between PM Oli and Musk the next month.

Reportedly, the conversation instead centered on Trump’s US election victory. No updates on progress are available since the conversation between the two.

During a parliamentary session last week, Nepali Congress lawmaker Rajendra Bajgain called on the government about Starlink’s entry into Nepal. Earlier, Bajgain had suggested that Musk couldn't hear PM Oli clearly during their meeting due to poor communication infrastructure at the PM’s office.

However, one key reason behind the stall is Starlink insists full ownership of its operations, which is against the country’s telecommunication law that mandates local shareholding of at least 20%, a rule that can be changed only by amending the Telecommunications Act.

Nepal isn’t the only country where Starlink is seeking a similar regulatory exemption—one notably South Africa, where the matter has become controversial. Others include Taiwan, Vietnam, Namibia, Lesotho and India. While India amended its foreign investment regulations in 2024 allowing 100% FDI in the sector, Lesotho provided an operating license this April to Starlink under full foreign ownership, against the backdrop of US’s tariff policies.

Starlink’s price structures

Across Africa, Starlink is providing internet services to 21 countries so far at affordable price ranges, as reported by Rest of World, with Starlink offering internet at half the prices than local internet service providers (ISPs) in Ghana. In other countries too like Kenya, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, and Cape Verde, Starlink is cheaper than their top ISPs, it reported.

With India geared up for its Starlink entry, prices are yet to be disclosed. Industry report estimates, as reported by several Indian media outlets, suggest the cost to fall between 3,000 to Rs 7,000 rupees for monthly subscription depending on plan and location, with additional one-time payment for the required hardware estimated between Rs 20,000 to 38,000. This turns out to be over seven times higher than what a typical broadband user in India pays but still likely to find users in regions with limited internet access.

In Bhutan, monthly price starts at 3,000 Bhutanese Ngultrum (Nu) [1 Nu=1.6 NRs] to 4,200 under its residential lite and residential standard plans. The high upfront hardware costs can, however, offset the benefits.

Considering these price structures, cost factors could be a major challenge in Nepal too. While the starting price as stated in Starlink’s website is $120 monthly, costs in many African countries is well below 50 dollars. Currently, Nepal’s leading ISPs—Worldlink, Subisu, and DishHome—provide monthly standard packages (200 mbps) at Rs 1,300, Rs 958, and Rs 1,283 respectively. Dependency on India for bandwidth import already makes the internet expensive in the country, and Starlink’s existing pricing models isn't economical either for its most intended target groups—those in remote and underserved areas.

While NTA has been granting tenders to private ISPs to build rural network infrastructures, geographical barriers and the associated cost challenges has made it unfeasible. For this reason, its broadband competitors are also backing the satellite ISP’s entry. During a ceremony in November 2024 marking 1.42 billion rupees Finnish investment in Worldlink, its managing director Dilip Agrawal said he’s been lobbying to bring Starlink to Nepal for two years. He noted that Starlink would cater to regions where building network infrastructures such as optic fibres and towers aren’t feasible.

Disruptive but—

The low-latency internet is getting positive reviews for addressing the digital division across the world. With Starlink’s competitive and accessible internet services, underserved African regions have become the major beneficiaries, with benefits expected through telemedicine, online educational material resources and fintech. In Nepal too, consistent internet connectivity can help the country make impressive strides in digital transformation.

Additionally, satellite internet can be crucial for a country like Nepal which is highly vulnerable to disasters, ensuring continuous connectivity for monitoring natural systems such as weather patterns, river levels and seismic activity; early warnings, and emergency coordination.

Yet important concerns remain.

In Africa, Starlink’s operations have raised questions regarding privacy breaches and national security considering limited control African nations have over where and how data is stored or routed. With rapid digitalisation across Africa, concerns regarding cybersecurity and exploitation have also surged.

Starlink’s entry also means underserved regions can have unfiltered internet exposure especially among children, posing risks of online harm. Globally, the trend of using the internet for recreational purposes rather than productive ones, leading to a potential loss of productivity and rising social issues, such as mental health challenges, has been making countries rethink their internet, and particularly social media policies.

This would be concerning for countries like Nepal too, which don’t have much bargaining and regulation capacity. Although the onus for this mostly lies on respective countries than the ISP.

Another major concern is the ISP’s adamant insistence on full ownership in every country where it seeks to operate, which not only raises questions regarding data sovereignty, but stands against the idea to provide local entities with a stake in critical infrastructures, ensuring certain economic benefits stay within the country. Additionally, since Starlink relies on minimal physical infrastructure on earth, it is unlikely to generate significant direct employment in the host country.

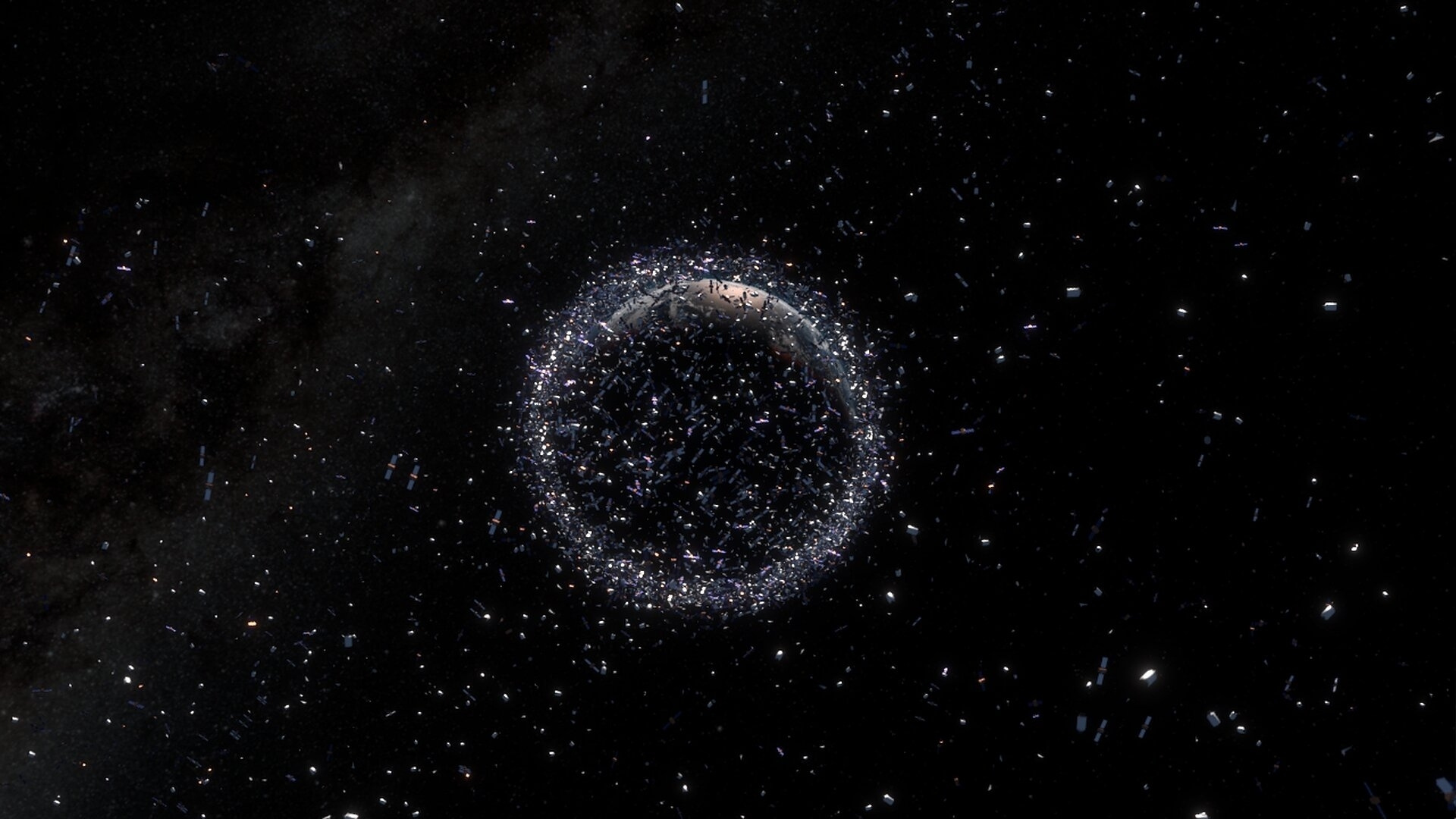

There is also a growing alarm over the impact on space. Starlink’s massive expansion of LEO satellites, which count in the thousands, is leading to space overcrowding. Orbiting Now, a real time satellite tracker, reports 12,354 satellites in space currently, with Starlink’s 7,300 LEO satellites. The congestion not only imposes risks of collisions but also Kessler syndrome—each collision creating more debris for additional collisions.

Meanwhile, the space competition is only heating up with companies like Amazon’s Kuiper Systems and China’s SpaceSail also gearing up to expand their spatial presence.

Read More Stories

Kathmandu’s decay: From glorious past to ominous future

Kathmandu: The legend and the legacy Legend about Kathmandus evolution holds that the...

Kathmandu - A crumbling valley!

Valleys and cities should be young, vibrant, inspiring and full of hopes with...

A week into Israel-Iran conflict

The latest escalation between Israel and Iran has entered its eighth day. Heres...