India-China Relations | Border Standoff | Offensive Realism | BRICS | Galwan Valley Incident

On November 18, 2024, India's External Affairs Minister (EAM) Subrahmanyam Jaishankar and China’s Foreign Minister (FM) Wang Yi held a sideline meeting in Rio, Brazil, indicating a progressive step between the two rival countries, since the tense border standoff that broke out in 2020 — the Galwan Valley incident, which killed 20 Indian and four Chinese soldiers.

This momentum was further solidified by the 23rd meeting of the two countries’ Special Representatives (SRs) in Beijing on December 18, 2024, which was led by FM Wang Yi and India’s National Security Advisor Ajit Doval.

This momentum was further solidified by the 23rd meeting of the two countries’ Special Representatives (SRs) in Beijing on December 18, 2024, which was led by FM Wang Yi and India’s National Security Advisor Ajit Doval.

The SR meeting followed a previous sideline meeting, an unexpected and a high-stake meeting, between the Indian PM Narendra Modi and the Chinese President Xi Jinping in Kazan, Russia in October 2024.

From Kazan to Rio to Beijing to Delhi, these interactions signal a breakthrough in recalibrating relations between the two countries post-2020 standoff.

Before these interactions, India has gradually resumed opening up to Chinese investments, after limiting them post-2020 incident.

Understanding the two press releases

Both the press release from the Rio sideline meeting and the SRs meeting in Beijing emphasised the critical need to maintain peace and stability in border areas, stressing the importance of mutually acceptable solutions to boundary issues. The Beijing meeting marked the first high-level engagement, aside from the sideline discussion, since frictions escalated in the Western Sector of the India-China border in 2020.

Following a disengagement agreement in October 2024, the two countries restored stability along the border. Both SRs acknowledged the importance of preventing future incidents and took steps to strengthen coordination between diplomatic and military channels to achieve this goal.

Offensive realism

The recent engagements between India and China can be analysed through the lens of Mearsheimer's theory of 'Offensive Realism', which posits that a superpower must manage its immediate neighbors to secure its hegemony. Else it shall become entangled in neighborhood issues, limiting its potential at global orientation. Mearsheimer argues that the United States became a global superpower in part because none of its neighboring countries posed a significant threat.

In this regard, India with its extensive coastline and relatively weaker rivals holds a strategic advantage over China, whose maritime navigation capabilities are more constrained compared to India's. This geopolitical reality allows India to exert influence in global politics, positioning itself as a ‘middle power’, which Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been exercising since his rise in 2014.

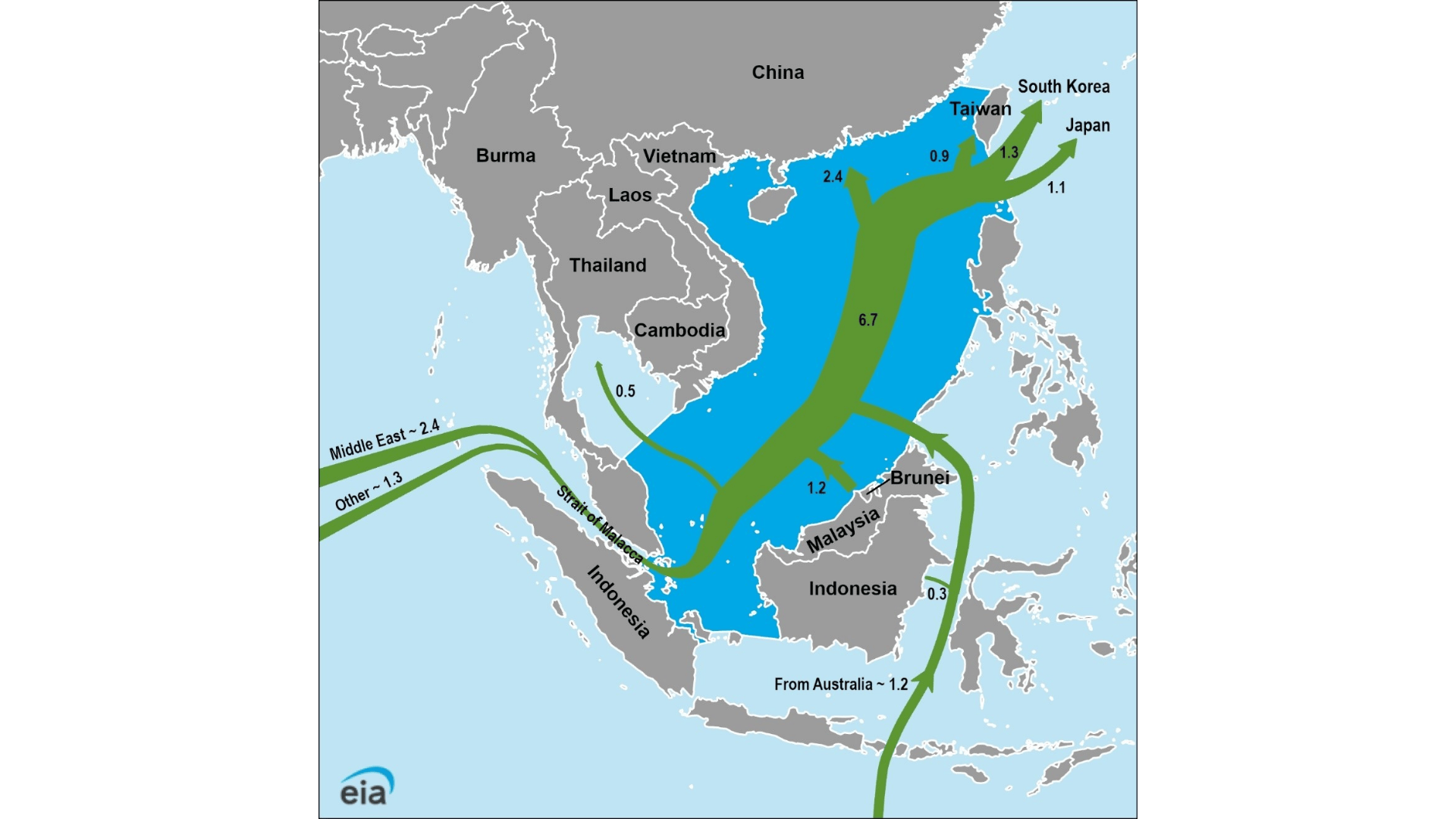

For China, maintaining cordial relations with India is crucial to protect the security of its international trade routes, given concerns about the potential blockade in the Strait of Malacca. In the broader geopolitical context, India is perceived to employ strategic choke points through the Strait of Malacca and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands against China, whereas China engages in similar tactics against India through the Himalayan region and Arunachal Pradesh.

International scenario

The Rio sideline meeting between the foreign ministers of India and China a few weeks after the U.S. presidential election results, where Donald Trump secured his second term holds significant geopolitical weight.

Trump’s China-approach is well-documented — direct and at times confrontational, particularly in the areas of trade and technology. The US-China relations are poised to undergo a profound test in the coming days.

Trump has also referred to India as ‘a very big abuser’ of tariffs in the recent past. But his relationship with India, especially with the Indian PM Modi has been notably close. Even under the Biden administration, India’s geostrategic importance and its ability to counter China has compelled the US to reinforce a stronger relationship with India.

Additionally, the influence of the Indian diaspora in the U.S. is significant and impactful with potential to leverage Indian foreign policy in the Trump administration.

Against this backdrop, India and China’s agreement to disengage along their border is a mixed step, especially for the smaller countries in South Asia—Nepal, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, Maldives. An old saying that when two elephants fight—or even make love—the grass gets trampled resonates here. The two giants may be signalling a thaw in relations but geopolitical implications are far more nuanced for those in their shadows [more on this in the next piece].

India and China, through these engagements, are planning an administrative-level meeting (Foreign Secretary-Vice Minister) to strengthen their relationship through institutional frameworks. This means the ongoing dialogues are moving beyond surface-level talks, while their effort seems to transform political rhetoric into meaningful actions. For the small players in South Asia, this effort could have significant ripple effects — either greater regional stability or increased complexity of aligning with one side or the other.

Convergences and divergences

The term ’convergence’ and ‘divergence’ has been a familiar refrain in the India-China dialogue, yet it remains a concept more often discussed than realised. Despite repeated acknowledgement of shared views and differing views, both countries have struggled to turn these discussions into tangible outcomes. At their Rio sideline meeting, both countries once again acknowledged their convergences and divergences on global issues in their press release, but this time, they emphasised the critical need to working together constructively, particularly within forums like BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

Before COVID-19, the two nations had developed a framework called ‘2C’ — competition and collaboration, which recognised that the rise of one nation inevitably affects the other. India and China found it crucial to work collaboratively while fostering healthy competition with the intention of adopting a win-win approach rather than a zero-sum game.

At last,

In Rio, the Indian EAM reaffirmed India's commitment to a multi-polar world, including a multi-polar Asia. In contrast, China's vision of a multi-polar world, as demonstrated by its global engagements under Xi Jinping since 2013, involves China positioning itself at the centre. While both nations express support for a multipolar world, their actions diverge significantly. It is vital to observe how this dynamic will unfold in the coming years.

For international relations scholars and pundits, the key to understanding this evolving landscape lies in observing China’s navigation strategy. China seeks to position itself as a dominant power in a multi-polar world, but it also must accommodate India’s aspirations to be the voice of the Global South, which it prioritised during its G-20 presidency in 2023. The African continent, which largely comprises these countries, has seen significant business and development initiatives from both the West and China. As India pushes to represent the Global South, collision between the two countries is likely, as both vie for influence in the region.

Additionally, FM Wang Yi acknowledged the global significance of stabilising India-China relations, stressing the need to manage their differences. This was evident during the Russia-Ukraine war, where India adopted a neutral stance, emphasising peace rather than aligning with either side. While China has a longstanding friendship with Russia, it has also refrained from providing military support, unlike North Korea. India and China’s neutrality r has had a significant impact leading to the continuation of the war and thereby damaging the global economy and economic stability. The war could potentially have come to a conclusive end early on, sparing the world from two years of human loss and suffering had the both countries taken assertive positions.

When both India and China share convergent views and actions on global issues such as climate change, terrorism and trans-border crime, it can become a significant asset for humanity. However, their divergent views on world politics present challenges and consequences.

India aspires to become an influential ‘middle power’ by balancing relations with both the West and Russia while leveraging significant strategic benefits. On the other hand, China aligns itself as part of the de-facto Russia-China-Iran-North Korea axis opposing the Western world. Additionally, domestic political factors, steeped in civilisational differences, often create complications in building relations and cooperation. As both countries hold sway over the future of Asia—and by extension, the global economy, they must find ways to limit rivalry and geopolitical adventurism.

Read More Stories

Kathmandu’s decay: From glorious past to ominous future

Kathmandu: The legend and the legacy Legend about Kathmandus evolution holds that the...

Kathmandu - A crumbling valley!

Valleys and cities should be young, vibrant, inspiring and full of hopes with...

Today’s weather: Monsoon deepens across Nepal, bringing rain, risk, and rising rivers

Monsoon winds have taken hold across Nepal, with cloudy skies and bouts of...