Antibiotic resistance | Bacterial infection | Public health crisis | Health infrastructure | Medical

Once considered a ‘magic bullet’ in modern medicine for fighting infections caused by bacteria in the human body and heralded as a ‘miracle drug’ that saves millions of lives, the effects of antibiotics have been waning.

The increasing overuse and misuse of antibiotics, along with other factors, have paved the way for a dangerous phenomenon globally: antimicrobial resistance. Nepal is no exception, with the situation proving to be alarming.

Bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites are among the microbes that overrun a human immunity system. To cure infections induced by them, antibiotic, antiviral, antifungal, and antiparasitic drugs are prescribed. The microbes over time develop resistance against said drugs collectively known as antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Notably, such resistance other than for antibiotics is less common, with antibiotic resistance (ABR) being a more prevalent form of antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Data shows 6,400 deaths in 2019 in Nepal are directly attributed to AMR while an additional 23,200 deaths were associated with it, outnumbering deaths from neoplasms, tuberculosis, respiratory infections, gastrointestinal disorders, maternal and neonatal conditions, diabetes, and kidney diseases.

The scale of the impact poses a significant risk to public health, the efficacy of medical treatments and the country’s healthcare system as a whole, with health experts referring to it as a ‘silent pandemic’.

Globally, 4.71 million deaths were associated with bacterial resistance in 2021, and 1.14 million directly attributed to it.

How does antibiotic resistance (ABR) transpire?

ABR occurs when bacteria adapt, mutating their genes after overtime exposure to antibiotics. Not only that, these resistant microorganisms, known as ‘superbugs’, pass resistant genes to their offspring.

High resistance means antibiotics fail to treat the infections, which persist to become severe and unmanageable leading to longer illnesses, costlier treatments, and ultimately death.

In May 2024, the World Health Organisation (WHO) released a new list of top antibiotic-resistant bacteria, featuring 24 pathogens (disease-causing organisms or agents) from 15 families. There is an addition of seven new pathogens from the first-ever list published in 2017, which had 17 pathogens from 12 families.

As for treating these growing resistant bacteria, a WHO review of the current pipeline for new antibiotics reveals only 27 antibiotics are in clinical development targeting two pathogens deemed critical by the WHO. While only 12 new antibiotics were approved between 2017 and 2021.

A week ago Dr. Valeria Gigante, a team lead within the WHO’s antimicrobial resistance division posted on her LinkedIn account that it takes about 10 years and approx. 1.2 billion dollars investment to develop a new antibiotic while the resistance builds within two years after it has reached the market.

For these reasons, health experts are already ringing the alarm bell, warning that the world is already in a post-antibiotic era, where antibiotics are no longer effective.

The WHO has described antibiotic resistance as the greatest threat to global health, while South Asia — particularly India — is frequently referred to as “the epicentre” of the crisis for the widespread use of antibiotics in the region.

Death forecast for 2025 to 2050 in South Asia is estimated to be at 11.8 million — implying that Nepal too is on the brink of facing dire consequences.

Studies show a bleak picture in Nepal

Numerous studies since 2008 have reported varying rates, mainly high levels of antibiotic-resistant bacteria prevalent among Nepalis.

A 2021 study that studied electronic and paper-based hospital records of 1,804 patients from Patan Hospital with Staphylococcus aureus infection found that 57% had Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Staphylococcus aureus is a common bacteria on our skin that can cause difficult-to-treat infections such as skin, wound, blood, urinary and respiratory infections.

One of its strains has grown so resistant to widely used antibiotics that it is now classified as MRSA, which is known for aggressive spread across hospital and long-term care settings and is linked to a high number of deaths worldwide.

Earlier, a 2008 study in Pokhara had also found a high prevalence of MRSA in school children under the age of 15 (56.14%, n=57) and hospitalised patients (75.56%, n=45) when their specimens [nasal swabs of children and pus and wounds of patients] were tested.

Similarly, a study from Shahid Gangalal National Heart Centre in 2018 found that 84 (91.3%) out of 92 samples were multi-antibiotic resistant tested from its inpatients and OPD visitors.

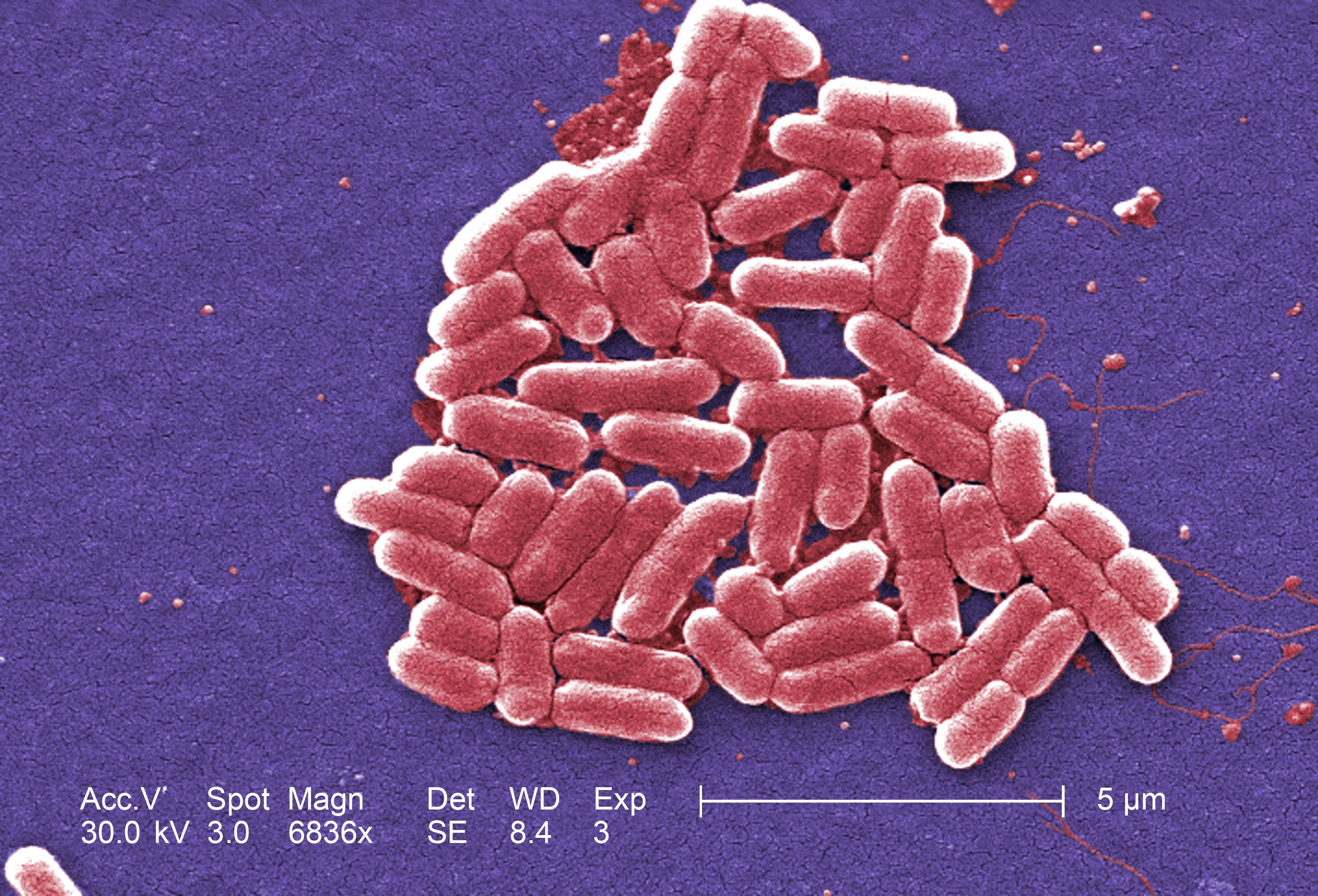

Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae were found to be predominantly resistant. Both are usually present in the human gut and are infamous for causing severe urinary tract, bloodstream, abdominal, and respiratory tract infections and is one of the top antibiotic-resistant bacteria on the WHO list.

The same year a study covering B&B Hospital found a similar high level of ABR to all commonly used antibiotics.

Similarly, in a 2019 study of 1,865 inpatient samples with urinary tract infections (UTIs) taken from TU Teaching Hospital, 53.6% showed resistance to multiple antibiotics, while 84.3% showed resistance to at least one antibiotic. Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae were again the most resistant bacteria.

A cross-sectional survey at Manmohan Hospital in 2023 also found similar results. Most antibiotics investigated were found to be resistant; Escherichia coli the most prevalent bacterium, followed by Salmonella typhi, Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae.

A recently published study conducted amongst patients suffering from surgical site infections at the National Trauma Center showed resistance to several routine antibiotics administered. Enterobacterales, which also include Escherichia coli, showed resistance to multiple antibiotics. First-line antibiotics such as Penicillin worked poorly, while stronger groups of antibiotics showed higher efficacy.

What is behind the growing resistance?

“The first rule of antibiotics is to try not to use them, and the second rule is trying not to use too many of them,” says an ICU guide. Beyond this, irrational use of antibiotics is the major driver of the rising resistance, a point on which many experts strongly agree.

“The primary reasons contributing to antibiotic resistance in Nepal are overuse and misuse of antibiotics, limited public awareness and educational gaps, inadequate hospital practices, and the use of antibiotics in animals for growth and disease prevention,” explains Sagar Aryal, a microbiologist and founder of Microbe Notes.

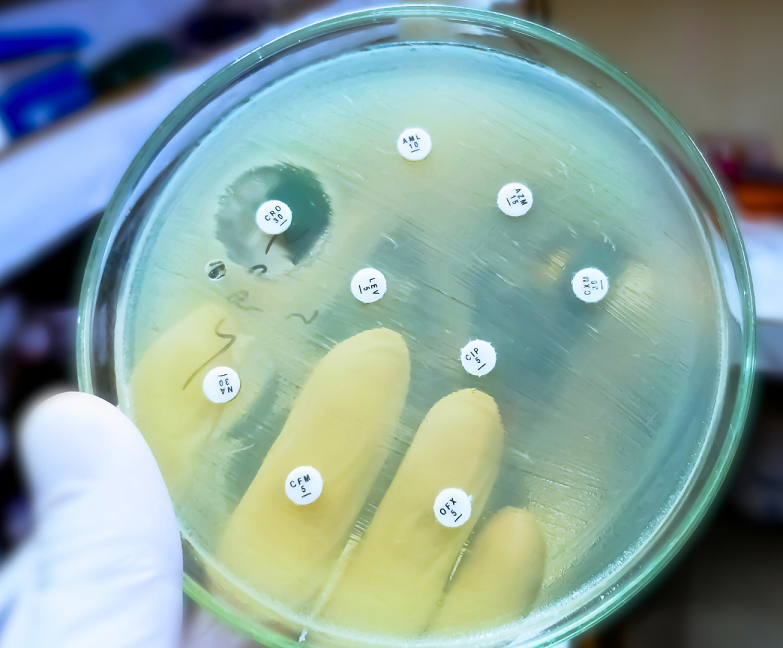

One major concern is the reckless prescribing practices among healthcare workers. A majority of patients receive unnecessary concurrent prescriptions for multiple antibiotics without bacterial confirmation or susceptibility testing. Even for conditions that do not require antibiotics, such as colds, coughs, and diarrhoea.

According to a 2019 study, physicians failed to follow essential drug lists standard, prescribed too many antibiotics and selected name-brand medications over generics. Graduate students from St. Xavier’s College who conducted thesis research at public hospitals in the Kathmandu valley observed a high prevalence of commission-based prescribing of selected brands, a practice many believe is rampant in Nepal.

Physicians were also found to be writing multiple prescriptions at once, all of which increased expenses, exacerbated antibiotic resistance, and put patients’ health at risk.

Haphazard prescription and use of antibiotics were found in intensive care units too. A latest survey found that only 14.37% of prescriptions had specified clear doses and only 27.5% adhered to treatment guidelines. When 61.1% of samples were sent for lab tests to confirm infections, only 26.78% came back positive for infection, suggesting that many patients may have received antibiotics without actually needing them.

In this regard, Dr. Megha Raj Banjara, Associate Professor of Microbiology at Tribhuvan University suggests, “Clinicians and researchers should collaborate closely to ensure antibiotics are prescribed responsibly, preserving their efficacy and minimising resistance.”

Another major driver is self-medication. Alexander Fleming, who discovered penicillin, had predicted 79 years ago that oral administration would lead to “self-medication and all its abuses” in the future. It appears his prediction is coming true.

30% to 60% of the population self-medicate in the country aided by easy access to over-the-counter medications. A 2021 study covering nine wards of the Kathmandu Metropolitan City found that 78% of people practised self-medication, primarily for common colds, headaches, fevers, and coughs. While in Eastern Nepal, a 2020 survey that covered 312 community pharmacies showed that almost 35% of them had dispensed antibiotics without a prescription, which also reveals the problem of self-medication.

Some commonly used over-the-counter antibiotics include cefixime, cefpodoxime, amoxicillin, ofloxacin, clotrimazole and metronidazole, among others.

One major reason for such reckless usage is a lack of understanding about the proper use and harms of antibiotics when misused.

A cross-sectional survey in eight districts that interviewed clinicians, private drug dispensers, patients, laboratories, public health centres/hospitals, and livestock farmers revealed that 84% of respondents (n=516) were unaware of antibiotic resistance.

One-third of respondents thought antibiotics could treat virus-induced ailments such as the flu, measles, and even HIV/AIDS. However, other findings revealed that the majority of the pharmacy personnel (76.9%) recognised that dispensing antibiotics without a valid prescription is a problem, and almost 27% considered it illegal.

Another study in 2018 in Eastern Nepal, however, showed that 81.84% of respondents were unaware of antibiotic resistance, and 94.64% used antibiotics inappropriately. Notably, the research found out that some community members of Kapilvastu Municipality were not aware of the term ‘antibiotics’ although using them indiscriminately. This underscores the challenges arising from disparities based on region, ethnicity, educational background and other differences in the country.

Dr. Meghnath Dhimal, Chief of the Health Research Section at the Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC) further points out, “Almost one-third of outpatients buy antibiotics without prescriptions, and a quarter don’t complete their course. WHO indicators show that 37.8% of prescribed medicines are antibiotics.”

Experts also point out that most patients stop the medication once conditions improve, and go as far as recommending these drugs to their friends, peers, family, and relatives without any medical prescription or caution.

Hospitals can also be a breeding ground for highly resistant bacterial pathogens when their infection prevention and control practices are inadequate and healthcare quality standards are poor. In such scenarios, patients taking their medications back home and interacting directly with family members run a significant risk of transferring resistant bacteria.

To make it worse, neutral bacteria in the environment can contract resistant genes, further spreading antibiotic resistance. To put it into perspective, most healthcare facilities in Nepal mix their hazardous medical waste with regular municipal waste, instead of treating it.

Meanwhile, most studies in Nepal are restricted to tertiary care institutions, which do not adequately document the true prevalence of microbial resistance, including antibiotic resistance.

Antibiotic residues in the food we consume

Multiple studies reveal high levels of antibiotic residues in poultry meat in Nepal where its per capita consumption is rising. Nepal Commercial Poultry Survey (2014-15) shows an average Nepali consumed 4.1 kg of chicken per year, which rose to 7.57 kg in 2021. These residues can occur when veterinary antibiotics are used in food-producing animals to prevent infections in them and promote their faster growth.

A 2021 study found that 90% of the 30 large poultry farms, each with flocks exceeding 100,000 chickens, used antibiotics. This widespread practice included a significant abuse of Colistin — a last-resort antibiotic used to treat severe multidrug-resistant infections in humans — despite a nationwide ban on colistin in feed in 2016.

Dr. Banjara considers it one of the major factors in the rising resistance in the country.

“The porous southern border allows farmers to obtain antibiotics banned here,” explains Banjara, “which are often used indiscriminately, leading to residual traces in animals.”

The medication has been linked to adverse reactions such as harm to the kidneys and nerves, severe allergic responses, skin tingling, seizures, respiratory distress and the development of new infections on top of preexisting ones.

Another study detected the presence of antibiotic residues in 22% of the meat samples from the Kailali and Kavre districts. Each sample out of 55 meat samples (muscles and liver) of poultry (41), goat (12), buffalo (9), and pig (4) from Kailali and Kavre was separately tested for different groups of antibiotic residues.

However, monitoring of residues in meat other than poultry is limited, despite their growing composition in the diet.

Several studies have also found fresh milk containing antibiotic residues exceeding the limits set by the veterinary standard.

Studies show contrasting pictures though.

A 2022 study that examined 935 samples from 14 districts found residues in only 1.6% of the milk, compared to other studies that have found higher rates of residues.

When 140 fresh cow milk was assessed from Kathmandu in 2017, all tested antibiotics (Amoxicillin, Sulfadimethoxine, Penicillin, and Ampicillin) were found way above their maximum residue limit (MRL).

Another 168 milk samples tested in 2019 from community dairies in Banepa and Panauti found different antibiotic residues in milk with sulphonamide exceeding the national limit.

Is Nepal combating the resistance aptly?

“Inadequate AMR surveillance infrastructure among others is one of the reasons Nepal faces a significant antimicrobial resistance burden,” shares Dr. Dibesh Karmacharya, Executive Director and Chairperson at the Center for Molecular Dynamics Nepal (CMDN).

Surveillance is key to tackling AMR, which started in 1999 by the National Public Health Laboratory (NPHL). But studies since then are still scanty and mostly limited to tertiary hospitals, lacking a broader representation of national trends. Similarly, about 1 in 5 (23%) health facilities in Nepal offer any TB diagnostic services, shows the country’s Health Facility Survey (NHFS-2021).

Aryal shares the same sentiment and suggests:

“The government and private sectors should invest in laboratory facilities and conduct national research to improve diagnostic capabilities.”

Amid increasing fears of an imminent public health crisis, Nepal recently introduced a National Action Plan (NAP) on Antimicrobial Resistance (2024-2028) with an estimated budget of Rs 4.59 billion for five years.

The action plan identifies five strategic priorities — awareness, surveillance, lower infection incidence, optimisation of the use of antibiotics, and access to sustainable resources.

In the past, Nepal has implemented various legal measures to combat antimicrobial resistance, including the introduction of bans and the National Antimicrobial Treatment Guidelines in 2014, which were updated in 2023. The guidelines were designed to guide doctors in prescribing the right antibiotics and doses, and several other commitments on paper to address antimicrobial resistance.

Despite these initiatives, challenges persist, including scant surveillance data in animal and agriculture sectors, lax enforcement of laws and regulations and limited public awareness.

The results have been disappointing so far.

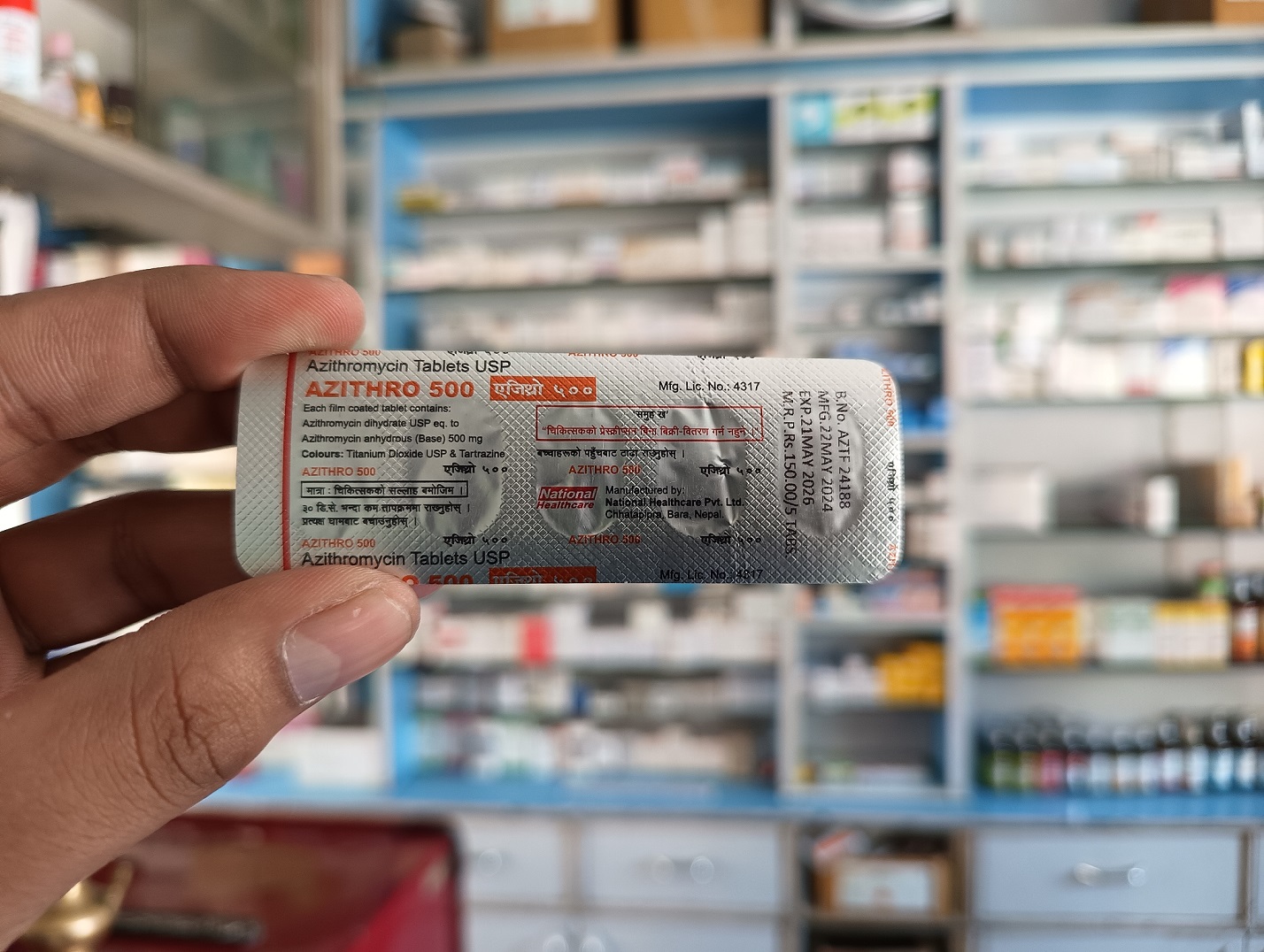

For instance, the Public Health Service Act 2018 bans the sale or distribution of antibiotics without a medical prescription and mandates the maintenance of quality standards for consumables, including food and meat. While recently the federal Department of Drug Administration (DDA) mandated a warning red line label on antibiotic packaging to curb self-medication.

Neither of these measures has proven effective.

In a random survey of seven Kathmandu city-based pharmacies that the_farsight conducted, none sought for prescription when asked for antibiotics.

Meanwhile, the fact that 90% of the 30 large poultry farms were using antibiotics, including banned ones, highlights the strikingly widespread nature of this practice. The study was conducted three years after the enactment of the 2018 Act.

And despite regulations and bans, a lack of knowledge among small farmers about making informed changes, along with profit-driven incentives, is likely to continue to hinder changes.

Moreover, relying on a mere ‘red line’ on packages of antibiotics, often difficult to distinguish from package design, to bring meaningful behavioural change is unrealistic.

They raise a valid concern: if the holistic ‘One Health’ approach — which addresses the impact of AMR on all health: human, animal, plant, and environmental — undertaken by the National Action Plan will succeed at all?

Edit by Sabin Jung Pande

Read More Stories

Kathmandu’s decay: From glorious past to ominous future

Kathmandu: The legend and the legacy Legend about Kathmandus evolution holds that the...

Kathmandu - A crumbling valley!

Valleys and cities should be young, vibrant, inspiring and full of hopes with...

Nepal’s high-altitude farms are thirsty. Could ice stupas help?

As snowlines rise and mountain springs run dry, Nepals high-altitude communities are facing...