STATELESS | CITIZENSHIP| FUNDAMENTAL HUMAN RIGHTS

This June marks my first anniversary of receiving a citizenship certificate with my name and passport-size photo. I became a Nepali citizen in June last year following a struggle of five and a half years, or as peaky as it should sound — little more than half a decade.

I vividly recall the day. My younger brother and a close friend of mine could not believe holding our respective citizenship cards in our hands. We let the cards under the sun so that the fresh ink would not spill, omitting the details written on it.

We were suggested to apply talcum powders that would quickly dry the ink. Upon returning home we placed the cards on our laptop table and under the fan. By no flick of a moment, we then became cautious not to cause any damage to our cards.

From enrolling into voters’ lists to applying for a National ID and then a passport, we rushed to use our citizenship for almost all documents a citizen needs. Bank accounts, KYC-verified e-wallets, personal account numbers (PANs) and SIM cards, you name it. My brother has gotten a driving licence too but I'm yet to apply for it. Our lives seem to have taken track. We now focus on our academics and career-building. Gates to explore opportunities in Nepal and beyond are now open to us.

Things however were disastrous earlier. Among various aspirations, for instance, I wanted to enrol at the Delhi School of Journalism (University of Delhi) for an integrated five-year journalism program following Grade 12, but I couldn't then. I was shattered.

Perverted politics that delayed the implementation of constitutionally guaranteed provisions made this wait feel endless. Politics of securing votes from our parents and alike, and otherwise politics of appealing to voters under the pretext of nationalism. I shall talk about it later in this piece.

The idea of acquiring a citizenship certificate must sound so basic to most “ipso facto” citizens. The range of my thoughts however was horrible during those five years. The toll on my mental health, the fear of settling for the least and being unable to do nothing as I aspired, or harbouring tendencies to engage in illegal conduct later in life to earn a livelihood in lack of citizenship.

Desperate for a way out, I sought a resolution — an expensive, health-tolling and gruelling process — at the Supreme Court. A few individuals who could access the concerned lawyers and the apex court in Kathmandu had received their citizenship upon court order. But it took them at least two years to get a verdict from the court. Notably, the chief district officers do not entertain verdicts from the district and the high courts as they can be contested at the topmost court.

It was in February 2023 when I filed a writ petition, asking for an interim order to open a bank account and PAN, among others. While the bank (a private firm) was ready to open an account based on the SC interim order the next day, the PAN office (a government agency) kept me in uncertainty for a month because they wanted to cross-verify the order with the SC officials. The designated officer later called me and finally issued my PAN.

Technically, my bank account and the PAN (with the petition number in the box of the ID number) are older than my citizenship which was issued to me five months after my writ petition based on Citizenship Amendments. I withdrew the petition presenting my citizenship at the court. My account of the court battle — the protagonists and the antagonists — can extend to a separate piece, which I may write later sometime.

I feel relieved now.

Unfortunately, hundreds of thousands remain deprived of their rightful citizenship cards, in contrast to what Article 10 of the Constitution mandates. The article ensures citizenship to every Nepali, which the state miserably does not seem interested in “identifying”, despite an inclusive constitutional foundation.

The government following the Amendments of 2022 has but celebrated what it thinks is an end of statelessness in Nepal, let alone maintaining data implying exact numbers and exact legal status of such individuals. However, my analysis is that the majority of them are youths whose energy and time are ageing without joining the formal economy. Were this to be accounted for in the financial books, Nepal would record a terrible economic loss, not to forget depletion in our social capital.

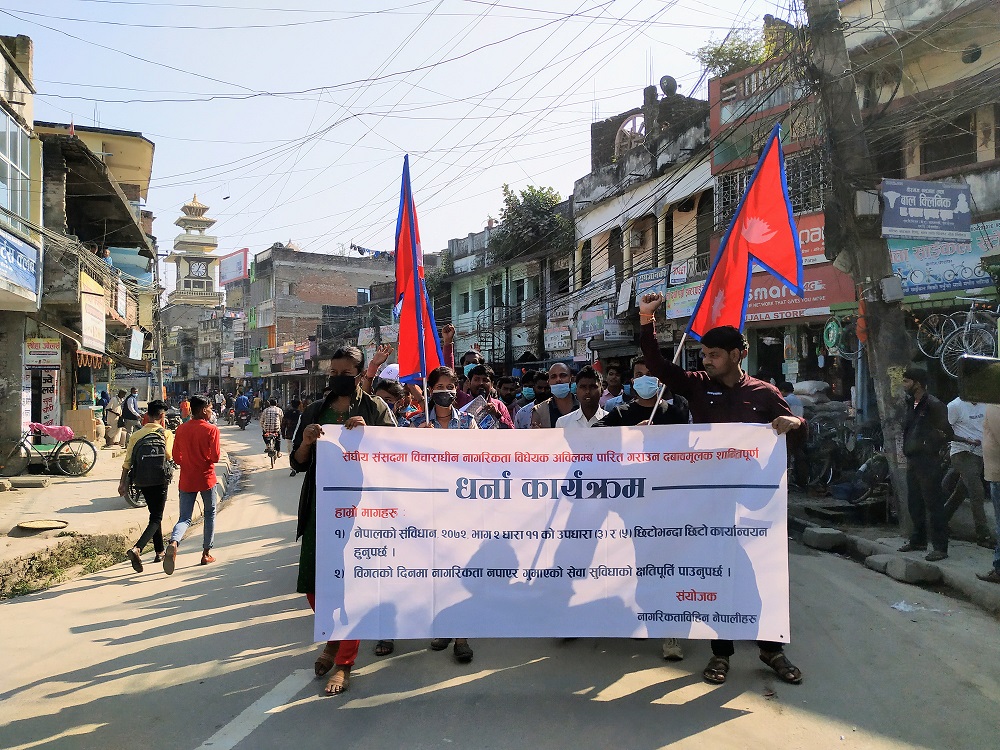

A group of stateless youth, who took protests on the road in Kathmandu demanding implementation of Amendments of 2022 forming a struggle committee earlier, often visits the Ministry of Home Affairs to pressurise the Ministry to issue a working procedure. However, to no avail as of now. The district administration offices (DAOs) across the country still refuse to issue citizenship to individuals with different legal statuses, citing a lack of the same working procedure.

Similarly, a few months ago the Ministry had been delaying to amend the then Citizenship Regulations, due to which citizenship in the name of the mother could not be issued immediately. Even after the Regulations came into effect, DAOs asked for documents as many as 19, including two self-declarations — one each from the mother and the child that the father is missing or unknown. I wonder if they ever asked the father and the child whereabouts of the mother in “normal” citizenship application cases.

Read: No, Citizenship Issue is Not Over Yet | Vivek Baranwal

Individuals — born to Nepali mothers and foreign fathers, and brought up in Nepal — are living in pure uncertainty. Most of them are in their 20s and are eligible to acquire citizenship by naturalisation. The Ministry of Home Affairs, as mandated in the Act, issues such citizenship upon receiving the application through the applicant’s respective DAO. However, nobody knows the time it may take for the Ministry to respond after the application.

For instance, three youths in a family in Birgunj that I am acquainted with have not heard from the DAO since their application some seven months ago. They were initially informed that it would take about two months. The above-mentioned working procedure is hoped to resolve these hassles, however suspicions remain as the Act (with amendments of 2022) mentions naturalisation citizenship applications must be presented at the Ministry. The family is now contemplating on filing a joint writ petition at the Supreme Court.

Nevertheless, an online application and appointment system as deployed for National IDs and passports can help manage such applications.

Individuals whose one of the parents has citizenship by birth and the other does not have any are turned down by the DAO, saying a lack of relevant directions (including working procedure) from the Ministry. However, in such cases, a working procedure may not merely work due to a limitation in Article 11 (3) of the Constitution.

The article requires both the parents to be Nepali citizens to pass citizenship by descent to their children. Here also, the type of citizenship the father holds determines the type of citizenship his children are eligible for.

For instance, if the father holds citizenship by birth, the mother must have citizenship — be it by descent, by birth, by naturalisation or by naturalisation by marriage. In my case, my father is a citizen by birth and my mother is a citizen by descent.

There are other instances of children deprived of citizenship — where the father does not have citizenship or he passed away without making one (in this case, the death registration certificate is available) and the mother holds citizenship by descent.

This provision does not apply to the father holding citizenship by descent. Such a man has an upper hand in passing citizenship to his children as disclosing the whereabouts of the mother or producing a marriage certificate is needless. This is the “normal” situation where the majority of us acquire our citizenship.

One more complexity lies under such cases where either one or both the parents received citizenship by birth after their child was born. Our citizenship laws hardly recognise children born before either one (primarily father) or both parents received their citizenship.

Children brought up at child shelters face difficulties at the bureaucratic level although the provisions addressing such conditions have existed since the first citizenship law was enacted under the regime of then King Mahendra in 1964.

Other conditions surrounding statelessness include elderly people who are left on their own and by age are eligible for social schemes covered by the government. But they lack citizenship to claim the benefits.

Most appear to be single elderly women whose children and/or grandchildren have disowned them due to property-related conflicts. Traditionally, women are exclusively made to depend upon their fathers, husbands, sons and later grandsons for document-related needs. Our bureaucracy turns a deaf ear when such cases reach them.

Over two years ago, I heard of a case from the Rasuwa district in Bagmati Province. An elderly woman was denied citizenship. Her husband had already passed away, while her son and her granddaughter had their respective citizenships.

The local representatives and villagers had frequently requested the DAO, particularly the CDO, which has the discretionary authority to issue citizenship in such cases, to look into the matter. They were also ready for due verification but her request was turned down. I am not aware of her present condition.

Stake of the State

The monoethnic and gender-based dominance in the power centres, including the bureaucracy, has historically retained the idea of Nepali identity to a certain ethnicity, face, race, lifestyle, language and culture. Thus, excluding ethnic and gender diversities when defining the Nepali nationality.

This history has repercussions to date. More or less the state machinery, including major political parties, gives continuation to the same legacy.

KP Oli-diktat CPN (UML) plays on a sheer nationalism card that is against a hassle-free citizenship acquisition other than the “normal” ones. Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP) shadows UML in the matter. In fact, RSP is the only party that issued a written statement protesting the 2022 Amendments.

Ironically, Rabi Lamichhane, the party chief of RSP, had to resign from his position as Home Minister and forfeit his parliamentarian status. The SC, in January 2023, annulled his citizenship that he had produced at the Election Commission to contest the 2022 general elections. Experiencing statelessness for 48 hours (Anaagarik in his own words) likely gave him a first-hand understanding of its implications.

The other parties Nepali Congress (NC), CPN (Maoist Centre), CPN (Unified Socialist), Upendra Yadav-led Janata Samajbadi Party Nepal (JSP Nepal) and Ashok Rai-led Janata Samajbadi Party (JSP) give the impression as if the statelessness is over.

In the previous House term, NC, Maoist Centre, Unified Socialist, intact JSP Nepal and Mahantha Thakur-led Loktantrik Samajbadi Party Nepal (LSP Nepal) played a proactive role in enacting the 2022 Amendments. NC president Sher Bahadur Deuba was leading the then coalition government while another NC leader Bal Krishna Khand was the Home Minister.

At the time, President Bidya Devi Bhandari had returned the amendment bill with suggestions to the federal parliament for review. Both houses again passed the bill without any changes to the content and sent it to the President for authentication. President Bhandari sat on the bill till her tenure ended in early 2023.

The new president Ram Chandra Paudel issued the same bill, which invited court cases and widespread controversy. The bill had become Act but the apex court put a temporary order. It put another toll on me as I had to travel to Birgunj from Kathmandu twice that month taking leaves from my campus and workplace, anticipating the Act finally being implemented. Anyways.

Moreover, the earlier governments between 2015 and 2020 had tried to resolve the issue like mine in separate yet similar circulars on different occasions. For instance, a 2019 Home Ministry directive asked CDOs to grant citizenship by descent to the children of those individuals who had obtained citizenship by birth. Then, the Supreme Court had, upon hearing similar writ petitions filed by advocates, struck down the ministerial orders.

The court said that addressing sensitive subjects such as citizenship should follow due process which is enacting required legislation. Following the second House dissolution in 2021, the KP-led government issued an ordinance with the content of previous ministerial orders in a bid to retain power by gaining support from LSP Nepal. The ordinance was also struck down by the apex court.

The larger parties in the parliament never carried the agenda of statelessness as seriously as the once Madhes-based parties including the JSP Nepal (before its split into LSP Nepal). They stood firm on their agenda to identify all kinds of possible statelessness prevalent in Nepal and constitutionally address them, including cutting down on hassles relating to citizenship application. But no later than 2015.

The second Constituent Assembly promulgated the new constitution, which addressed statelessness partially. Gradually, the Madhes-front diluted in subsequent electoral politics. They channelled their focus solely to constitutionally guaranteed citizenship rights by the end of the federal parliament’s first tenure.

Polarised public response

The public response on social media surrounding — the amendments and the protests for implementing them — was largely degrading and polarised. Instilled by ill-informed, or I think ill-intent, political leaders like Dr Bhim Rawal (CPN-UML) and Gyanendra Shahi (Rastriya Prajatantra Party).

The role of celebrated civil society members, intellectuals and experts was dubious. Most media outlets, national and local, initially appeared ignorant of the issue but reported heavily once protests hit Kathmandu roads.

Social media pages and channels, disguising themselves as news media and mass opinion builders, attempted to discredit the issue and the protests. They ran misinformed and uninformed content and narratives, intending to cash views and engagements by polarisation. So-called social media influencers and experts were no different.

The trend was so set that whoever wanted to come in the limelight would just blabber against the amendments, mongering fear and hate with narratives of Sikkimikaran and Fijikaran. For instance, a Facebook post went viral spreading the said narratives after Indrajit Saphi, national coordinator of Nagarikta Bihin Sangharsh Samiti Nepal, acquired his citizenship. You may go to his page and look at a few comments for a check, or refer to my earlier X (formerly Twitter) posts.

They all seemed to reinforce a long-run fear-mongering that foreigners — particularly Indians with whom Nepalis share an open border and religious, cultural and lingual ties — would maliciously acquire Nepali citizenship. A case in hand is a malicious video that went viral in 2019 claiming that Indian nationals have been crossing the border in droves to obtain Nepali citizenship after the 2019 directive issued by the Home Ministry.

Such social media posts and public responses to them continue to degrade people in the Terai plains, especially Madhesis whose surnames are Indians. “Madhise”, “Indian”, “Dhoti”, “Bihari”, “Modi ko Santan”, etc. are a few words used connotatively as racial slurs against those who talk in favour of resolving statelessness.

A good example is political leader Rajendra Mahato’s citizenship which is dragged into controversy time and again, posing questions about his loyalty to the nation. He clarifies well in his autobiography “Adhura Kranti: Sangharsha Matribhumi Kaa Laagi” that he applied for citizenship by birth through the Nagarikta Toli in 1977 (2034 BS). Then, people didn’t know much about citizenship — what it is, where to make it, and why it is needed. The then government did a commendable job mobilising Nagarikta Toli in rural areas, he says further.

On the contrary, Rabi Lamichhane’s case received public sympathy. (I leave it to you to make your own judgement on this perceived national identity.)

Mind you, though statelessness appears as prevalent mostly in the Terai-Madhes region, it is majorly a problem based on the intricacies of documents — founded upon racial, class, ethnic and caste discriminations, and bureaucratic ignorance and inefficiency in the past.

What gave the issue momentum and keeps it going?

The answer is pressure groups formed by stateless youths as I mentioned above.

They relentlessly protested in front of the federal Parliament building, at Maitighar Mandala and so on. Social media campaigns tagging ministers and lawmakers on posts and calling and texting them on their numbers. Multiple marches to respective DAOs and to Kathmandu. Submitting multiple memoranda to the DAOs, the Home Ministry, the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO), the President, the respective Chief Minister’s Office (CMO), the federal and provincial lawmakers and ministers, etc.

One of the protests I recall is youths with banners and pamphlets jumping in front of the convoy of then Home Minister Bal Krishna Khand in front of the Parliament building in New Baneshwor.

Another was a stateless youth attempting to set himself on fire in Maitighar which fortunately police intervened in time. He was immediately hospitalised and later survived his injuries.

However, a youth in Morang killed himself upon being denied citizenship as his family’s financial condition slumped. Such can be the mental toll.

For youths, citizenship is crucial as never before, unlike for earlier generations when the utility of the certificate was more or less limited to taking up government jobs and passports when only a handful of people would get a chance to ship or fly abroad.

In the present context, as layman's knowledge it should be, no citizenship means no education (home or abroad) and no employment (home or abroad) — not to mention the heavy mental and irrecoverable damage to career and social and economic life including owning a property.

A year has passed since the state granted me my citizenship, but over a hundred thousand are still fighting their battles in hope and desperation. It’s incomprehensible why the state can’t see all of it.

Read More Stories

Kathmandu’s decay: From glorious past to ominous future

Kathmandu: The legend and the legacy Legend about Kathmandus evolution holds that the...

Kathmandu - A crumbling valley!

Valleys and cities should be young, vibrant, inspiring and full of hopes with...

‘A run that grows forests’: Doko Recyclers’s eco-run links environment, fitness and corporate action

On the occasion of World Environment Day, Doko Recyclersa social venture into waste...