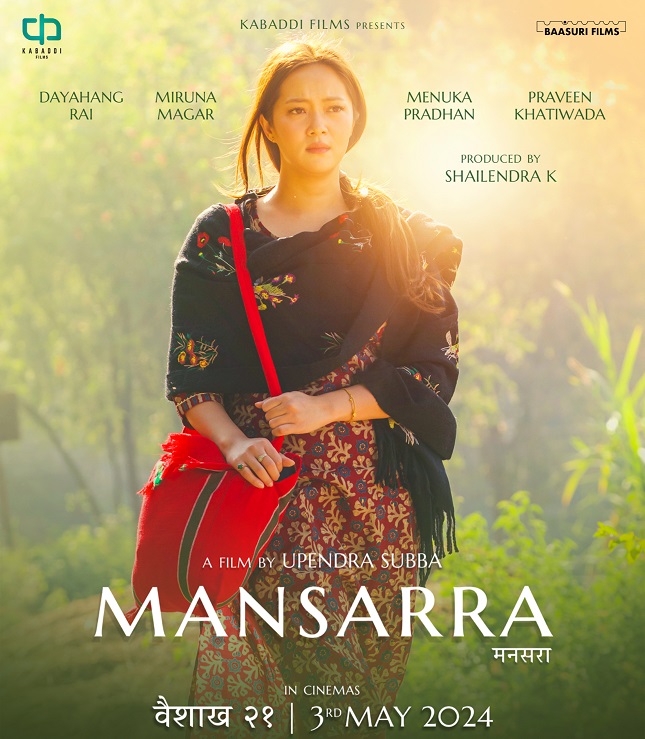

Mansarra | Nepali Movie | CULTURE | SOCIAL Drama | Infertility | NEPALI CINEMA

Hesitancy is gradually diminishing when it comes to watching Nepali cinema.

What was once about waiting for the movie to pop up on YouTube has transformed into eagerly saving pocket money for a seat at a multiplex. Nepali cinema is truly leaping.

‘Mansarra’, also written by Upendra Subba, is his third directorial venture after ‘Jaari’ (2023) and his directorial debut and critically acclaimed Kabbadi (2014).

Manrani Limbu (Mansarra), played by Miruna Magar, is a single mother looking after her son Tanchho. She earns her living by selling vegetables, and occasionally Raksi (traditionally distilled alcohol) and owns a pigsty. She chose to start a new life in Kathmandu after she learned about her pregnancy with Maanang, her lover who had migrated overseas for employment but failed to return as promised. As Maanang’s family hesitates to accept Mansarra, she leaves her village and migrates to Kathmandu deciding to raise her child by herself.

Dadhi Ram Pokhrel, played by Prabin Khatiwada, and Nani Maya by Menuka Pradhan — an inter-caste couple, are her neighbours.

Dadhi Ram is desperate for a son, driven by the imperative of fulfilling religious duties passed down from his father. When his first marriage failed to get him a child, he married Nani Maya in hopes of finally having a son. The second marriage bears no fruition either. Faced with childlessness, the couple turns to a fertility clinic for answers, only to discover that Dadhi Ram is sterile. The clinic proposes IVF treatment (an expensive reproductive health service that is mushrooming in Nepal) at a hefty cost.

The couple soon turns increasingly hostile towards each other. Their relationship strained by conflicts over childbearing, lack of trust, and Dadhi Ram’s growing bond with his neighbour’s family, ultimately wrecks their marriage.

Subba’s craftsmanship as a filmmaker and writer is top-notch. He has done a fabulous job with a simple and compelling story gently stirring the stigma revolving around infertility, and how women are at the front bearing its brunt, among other themes.

“Being a parent is the ultimate goal.” Society shoves this narrative down the throats of couples as indispensable. Couples who can’t naturally conceive or opt-out face relentless pressures, such as loneliness in old age, the erosion of family lineage, or the absence of sons to perform religious rituals.

And fanning through the pages of society, it is not hard to find actual stories where women are subjected to violence and exclusions for being unable to bear a child, especially a son. Women, almost all the time, bear the blame for infertility or are unfairly deemed responsible for the gender of the child.

Subba exposes this ignorance and hypocrisy exemplified by Dadhi Ram, who gets into two marriages in a futile attempt to father a child.

It is impressive how the film dives straight into this problem where the audience are immediately (in the opening scene itself) educated about infertility, prompting the question ‘K Baajhopan paap ho ra?’ (Is infertility a sin?). It neither shies away from delving into harsh social realities for men and their psychology from pressure to conform to standards of masculinity, including, for instance, fear and pressures of labels such as ‘Namarda’ and ‘Aputo’.

Dadhi Ram, however, rejects the idea of a sperm donor, arguing it wouldn’t make the child legitimate. It is ironic how his desperation has boundaries, which deepens when he fervently tries to persuade Mansarra that he is the ideal father for her son.

The portrayal of a single mother is heart-warming and is crafted subtly. Despite the struggles of being a single mother, she navigates her circumstances refusing to let her single status define her, and goes on with her life embracing each day with grace and fortitude.

The story that moves back and forth between the past and the present through sleek transitions, flows effortlessly and whimsically, without losing its grip. You can find the transition at its best when Solti Gang is performing the traditional Limbu dance in Mansarra’s front yard while she reminisces about Maanang’s dance when she first fell for him.

Mansarra is also a mirror to the beauty of the Limbu culture and cultural differences. The use of Palam and folk tales is continual throughout the movie adding colour to the storytelling. Both Manrani and Maanang, played by Dayahang Rai, who is on a quest for his long-lost love deliver this element throughout the film. Their poetic interactions and anecdotes carry the essence of Limbu’s roots and culture associated with human life.

If you are interested in more of these legends and folktales in Limbu culture, read this informative piece.

Subba employs symbols like Khuwa and Raksi, alcohol and milk, cow and pig, Gobar and Lidi, Janai and Palam through casual and descriptive dialogues to illustrate cultural differences, but his overarching message is one of mutual respect and co-existence. In a scene where Upendra Subba’s character visits his in-laws’ house, he performs the Sewaro ritual while his in-laws perform Dhog for their son-in-law, displaying that harmony between cultures is possible while contrasting it with scornful exchanges between families of the same ethnic group.

The film also skillfully delves into the multifaceted layers of the country’s socio-economic terrain serving as a poignant commentary. Observe closely, and you will be immersed in the gritty realities of Nepal’s impoverished communities, evidenced by dilapidated roads, the daily toils of low-income households, and the makeshift tin dwellings that give a portrayal of urban slums.

Different push factors (which don’t have to be wage differences alone) that drive people to abandon their hometowns and the state’s bias against home brews, which although deeply rooted in Nepal’s vibrant home brewing heritage and despite its cultural significance, renders it illegal.

Mansarra boasts compelling performances from its three lead characters, along with strong support from the ensemble cast. There is depth and nuance and no over-the-top or melodramatic portrayals among the characters. This subtlety lends authenticity to the narrative, allowing the audience to connect more deeply with the characters and their journey.

Miruna is perfect as Mansarra. Her character possesses a stronger undertone which she performs with excellence. She is loaded with love and sadness yet she doesn’t spill it all loudly but portrays it subtly. Her banters with Dadhi Ram are enjoyable. In the scene where Mansarra confronts Dadhi Ram, Miruna shines with her perfect dialogue delivery and emotional expressions, compelling Dadhi Ram for self-introspection on the idea of love and family.

Prabin Khatiwada’s performance as a flawed protagonist is outstanding. His character arc is a journey from being an orthodox Brahmin man and a selfish husband to becoming a sensible person who acknowledges his immoral behaviour and flaws and understands a thing or two about love by the end of the film. Prabin adds all the layers requisite to his character arc.

Menuka Pradhan is just brilliant. Her strong Newari accent adds to her character while her chemistry with as well as hostility towards Prabin is entertaining and convincing and justified. There are many instances where Menuka instills incredible resolve in her character by challenging and defying Prabin and refusing to succumb to his selfishness. Her palpable tension and raw emotion will capture the audience’s empathy and investment in her journey.

Other actors Satya Raj Acharya (the doctor), Hemant Budhathoki (the Khuwa maker), Viplob Pratik including child actor Nenahang Rai, and the director Upendra Subba himself all delivered convincing performances. None of them will get on your nerves.

The film also has its weak spots.

Dayahang’s character is ambiguous while his performance is average and lacks energy, but it’s buoyed by the strength of the poems and folktales he narrates. The ending seems stretched only to facilitate a harmonious reunion between Maanang and Mansarra.

Also, while the movie title is Mansarra, which by definition refers to a species of paddy that doesn’t sprout alone and has to be mixed with seeds of other species before planting, the character Mansarra goes against the nature of her name and continues to exist independently.

The film seems more engrossed in exploring, detailing, and intensifying the character of Dadhi Ram.

Yet, a strong storyline, deft direction, and a fantastic set of actors delivering captivating performances make Mansarra an engrossing experience.

Highly recommended!

Mansarra (2024)

Director: Upendra Subba | Cast: Miruna Magar, Prabin Khatiwada, Menuka Pradhan, Dayahang Rai | Genre: Social drama | Language: Nepali

Read More Stories

Kathmandu’s decay: From glorious past to ominous future

Kathmandu: The legend and the legacy Legend about Kathmandus evolution holds that the...

Kathmandu - A crumbling valley!

Valleys and cities should be young, vibrant, inspiring and full of hopes with...

A week into Israel-Iran conflict

The latest escalation between Israel and Iran has entered its eighth day. Heres...