Banking Liquidity | Credit | Money Supply

We often hear news that the economy or the banking industry is facing a liquidity crisis. Sometimes, they say it’s just credit crunch silly — a shortage of loanable funds and not exactly liquidity crisis but what’s the actual difference. Other times, the market is swamped with funds but the banks sit idle atop those idle reserves due to a lack of credit demand.

What do these banking terminologies/phrases/phenomenon mean and what are some of their implications? A simple explanation:

Background

Banks’ ultimate business is to collect deposits from individuals/institutions (shown in the liabilities side of their balance sheets) and lend to needy borrowers (assets side) — again to individuals/institutions — who use the credit in fulfilling their financial requirements.

In this process, banks require adequate liquidity to perform daily operations (such as processing withdrawal payments) including abiding several regulatory provisions. Deposits placed by individuals/institutions in the banks are short-term and volatile in nature, while the loans or credits issued by the banks are long-term. This creates a potential for liquidity stress. As a result, banks must maintain adequate liquid assets to meet short term financial obligations, such as varying daily withdrawal demands.

In general, liquidity refers to cash or any other cash equivalent assets which are used to meet short term financial obligations. A fraction of banks’ deposits is mandatorily parked at the central bank as liquidity. This system is called fractional-reserve banking — a common form of banking worldwide.

Banks also maintain a fraction of their deposits as vault cash and buy government issued bills and bonds which are other best examples of liquid assets.

If the banks are short on funds to repay their depositors, they also borrow money from the interbank market — manage adequate funds by trading currencies between banks and/or the central bank. The availability of sufficient liquidity displays their financial vigor and is one of the key elements to their growth.

Not having sufficient liquidity or sometimes even loss of market confidence can cause panic and bank run, leading to their collapse in no time. This can also set in motion systemic disintegration of the banking system — as these industry players are highly intertwined.

The onset of the 2007/08 global financial crisis can be explained by the fact that banks stopped lending to each other. This happened because they started doubting each other's financial strength after realising the scale of subprime lending within the banking industry.

Bank liquidity

Allow me to explain in more detail, specifically in the context of Nepal.

The banks and financial institutions (BFIs) in Nepal are currently allowed to lend up to 85% of the sum of their core capital and total deposits (CCD). This is called a CCD ratio — a prudential lending limit set with a view to utilise the rest of the funds in covering any liquidity requirements during contingencies. It was earlier set at 80% and relaxed lately through monetary policy 2020/21.

Out of the remaining funds, BFIs have to first set aside Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR) — park three percent (earlier four percent) of their total deposits as cash reserves at the Nepal Rastra Bank.

Second, banks have to maintain certain liquid assets in the form of cash (at vault) and money market investments like government securities (treasury bills, bonds etc), including the CRR. This is called Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR) — which is fixed at 10%, 8% and 7% for A, B and C classes of BFIs respectively.

Table 1: Regulatory provisions for liquidity level

Third, banks have to maintain Net Liquid Assets (NLA) of 20% of deposits. The NLA is the sum of placement up to 90 days and investment in government securities, vault cash and the CRR. This means NLA comprises BFIs’ deposit/placement (local and foreign currencies placed with other banks maturing in 90 days) and SLR.

The NLA can also be met by additional investment in government securities or by holding a higher level of CRR but meets the regulatory prescribed ratio without the need for the placements.

Moreover, BFIs are permitted to invest up to 30% of their core capital in the secondary market (barring stocks of other BFIs), and mutual funds but they don’t count as liquidity.

These regulatory liquidity requirements are mandated and adjusted by the central bank (increased/reduced) depending on the market dynamics for funds. If the CCD is increased and CRR and SLR are reduced, it frees up some funds for BFIs to lend, while a tight ratio means banks are expected to stay more liquid while the money supply is restrained. The manoeuvring of liquidity ratios is mainly exercised when banks face shortage of loanable funds helping them to cope up with credit crunch (discussed below). The monetary policy 2020/21 had eased the CCD ratio to 85% and reduced CRR by one percentage point for the same purpose.

On a day to day basis, liquidity management plays out in a different fashion. BFIs have to deal with a large number of daily transactions causing fluctuations in their respective liquidity requirements accordingly. As a result, they may require funds from different sources, such as the NRB or the interbank market, to meet their different needs such as compliance with the regulatory reserve requirements, prepare for payment needs arising from withdrawal claims and issuing loans to individuals/institutions.

The supply and demand for the NRB fund also determines the liquidity in the banking system. The NRB has implemented Interest Rate Corridor (IRC) to keep interest rates at desired level. Under the corridor, it exercises ceiling and floor in interest rate and stabilises liquidity.

The IRC comprises three liquidity instruments — Standard Liquidity Facility (SLF), Overnight Repo and Term-Deposit (weekly deposit collection). The BFIs exercise the SLF when they cannot manage daily liquidity from the interbank market. Here, the NRB acts as a ‘lender of last resort’ for BFIs to manage daily liquidity requirements.

The SLF and 'Repo; inject liquidity in the system (NRB lends out to BFIs) while 'Reverse Repo' and deposit collection by NRB (BFIs place deposits at NRB) mops it out.

The SLF forms the ceiling rate (at five percent) of the corridor while the term-deposit (Deposit Collection) forms the floor rate (at one percent). Overnight repo costs three percent.

Market liquidity

The above explanations primarily focus on the internal mechanisms of regular liquidity management within the banking sector.

In modern economy, banks also require a sound cycle of liquidity flow to provide credit, without which they can’t grow, neither the economy. Credit creation is its major function. For that, it needs funds to flow through its system.

If individuals/institutions/governments withdraw funds from banks or market and either store them in their vaults or employ them in the informal economy, the money doesn't flow back into the banking system, preventing banks to create further credit. We then face the problem of credit crunch.

It however doesn’t mean that banks aren’t sufficiently liquid anymore to meet their daily financial obligations — it’s just that the banks don’t have sufficient money to lend, which leaves credit demand unmet. If this shortage persists for an extended period, it can have severe economic consequences, as the inability to lend also hinders the creation of new deposits.

Time and often, Nepal's BFIs face this unique credit crunch/shortage for several economic reasons, which can be understood by examining different economic indicators.

Table 2: Some useful economic indicators

Among many contributions to the country's economy like strengthening foreign exchange reserves and current account and reducing poverty, the remittance inflows also contributes to increasing deposits at BFIs — strengthening their fund position and enabling them to issue more credits. However, there’s a catch.

Table 3: Some useful economic indicators

The remittance income effect on liquidity flow into banking system is negated by the country’s rising import bill. Nepal is one of the largest recipients of remittances but in essence those incomes don’t stay in the domestic banking system — they exit the economy covering the country’s much larger import bills.

On the other hand, Nepal’s export volume, as we all know, is too miniscule to make a difference.

Table 4: Some useful economic indicators

Government spending strengthens the fund position but—

Another crucial reason behind credit crunch is governments’ failure in spending.

While the federal government’s budget plan can help stabilise liquidity in the economcy at the desired level, this can only be achieved if all levels of government are able to effectively spend their allocated funds.

First, the governments can run deficit spending (not a necessary condition). Deficit spending, it is argued, also stimulates economy through monetary expansion.

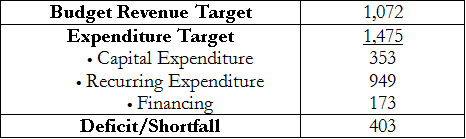

Table 5: Budget Plan 2020/21 (In NRs billion)

How the government runs deficit — manage its planned budget shortfall — is through public debt and foreign grants. Economists use many phrases for this deficit situation: deficit spending or budget, fiscal or government deficit.

Second, it must effectively spend what it has collected (for instance, tax revenue) and parked in its treasury (a necessary condition). The problem arises with the governments (federal and local) failure in spending these revenues and borrowings (public and foreign) earmarked for development/capital expenditures.

While governments have no trouble covering recurring expenses, such as paying government salaries, successive administrations have consistently failed to implement their capital expenditure plans. This includes delays in various development projects, both small and large.

When funds remain unspent, they essentially stay in the government’s coffers, held at the treasury. This means the money doesn’t flow into the market and, subsequently, into the banking system, effectively absorbing it from circulation. When funds are collected but not reintroduced into the system through spending, there will be problems.

In the seven months of the current fiscal year, the government has been able to spend only around 33% of its capital budget, and although it may spike later during the end of fiscal year, such irregular flows do not create a stable payment cycle.

So, despite flooded with idle deposits earlier due to the pandemic, the banking system is now worried about the looming credit crunch when economic activities are showing signs of pick up.

When the system is too liquid!

The pandemic harshly halted economic activities, also halting the credit demand. As a result, the banking sector was left with idle deposits. During August 2020, liquidity in the commercial banks was recorded at an excess of NRs 175 billion.

In such cases, the central bank can stabilise the liquidity by performing money market operations i.e. issuing reverse repos, or deposit collection to mop up excess liquidity from the market.

The growth has rather pushed down the interest rates — an obvious result of a declining economy and deposit growth outpacing credit. While lower interest rates and easier access to credit (due to limited credit options currently available) may benefit some borrowers, it could have unintended consequences if the real economy is struggling, lending priorities are misaligned, and there is a significant amount of idle funds in the system.

There is a risk that funds may flow into unproductive sectors (such as trading) or unorganized sectors (like real estate), or become concentrated in a few sectors, leading to the creation of bubbles or inflated asset prices (such as stock or real estate prices).

To put it into perspective, consider the increase in margin lending, NEPSE, and market capitalization during the pandemic period.

Margin lending has reached Rs 77.35 billion this year — an increment by 70.6% when compared on the y-o-y basis and by 53.5% in seven months of the fiscal year, says the NRB’s seven month macroeconomic data.

NEPSE and market cap has also registered a considerable rise (see chart below):

The growth was also aided by the central bank's latest adoption of a relaxed monetary policy. The margin lending limit was increased by five percentage point to 70 percent of the share value while the valuation consideration was reduced to the average share price of 120 days from 180 days.

Read More Stories

Kathmandu’s decay: From glorious past to ominous future

Kathmandu: The legend and the legacy Legend about Kathmandus evolution holds that the...

Kathmandu - A crumbling valley!

Valleys and cities should be young, vibrant, inspiring and full of hopes with...

A week into Israel-Iran conflict

The latest escalation between Israel and Iran has entered its eighth day. Heres...