Economic Analysis | Macroeconomics | Inflation | Interest Rates

For decades, Nepal’s economy has lagged as one of the least developed in the world, leading to persistently low living standards for much of its population.

In this long read, we assess Nepal’s rising price graph (high inflation), its high interest rate environment (high borrowing rates for businesses and households) and pay gap among formal workers and how they, combinedly, have long held the economy hostage impeding spending, investments, businesses and welfare.

Inflation

Inflation is a rise in the general price level of goods and services that consumers usually consume. In simple words, it is the rate at which consumption costs (consumer prices) or the living costs are changing.

The Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB), the central bank of Nepal, measures the country's inflation by computing Consumer Price Index (CPI) annually. The index comprises the price of a basket of essential goods and services that households typically consume. The basket and the weight of the components in the basket are subject to adjustments as the typical consumer preferences change.

Inflation is also measured vis-à-vis rural, urban, food and non-food and regional basis, each measure using different basket of goods, giving glimpses of how prices are changing within each category, or it can be about a particular item, say fuel inflation or wage inflation (wage is the price of labour).

The average of change in the monthly prices is the final annual inflation rate that we usually see in research reports. Although high inflation is economically hazardous, inflation, in general, isn’t discussed at public and media forums as intensely and minutely as needed. The amount of analytical and detailed coverage inflation has received in the news sphere makes it seem like a trivial issue. But in advanced economies, inflation has long been a focal point. In the seventies, when the US endured a chronic inflation, it was considered the ‘public enemy number one’. That fear is back in the post-pandemic US economy.

Nepal too faced similar high inflation during the seventies (see Graph 1 below). Yet, despite the recurring nature of this issue, its inner workings and criticality is less understood by the public. As a result, inflation continues to be treated as a distant challenge, with little impact on the perceived legitimacy of the central bank or the ruling political parties.

Inflation Determinants

A globally popular theory about inflation, in accordance with monetary economics, is that money supply is its main determinant. It postulates that it is the money supply management that controls the economy. When more money chases lesser economic output in the market, it shores up the price level. Inflation, as asserted by the renowned neoliberal monetarist Milton Friedman, "is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon". Many hold the underlying theory as true, but not everyone is convinced about its pragmatism like Keynesian economics.

The central principle of this school of thought is that government intervention can play a key role in stabilising the economy. Further, it argues that inflation is not just monetary in nature but driven by demand-supply imbalance as well. The Keynesian economics asserts that by influencing aggregate demand through interventions like government spending and taxation, one can determine/manage the inflation and the economy.

When aggregate demand for goods and services outstrips supply, demand-pull inflation sets in, which is why aggregate demand is a fundamental element of inflation, Keynes argued. For instance, chicken meat price rises if demand goes up but there is a supply gap. The example carries relevance to Nepali market because it is observed that among few goods and services that receive press coverage like bank interest rates (cost of capital) and fuel prices (remember students resorting to burning tires protesting fuel price hikes), another is chicken meat prices (akin to burgers in the US).

A critical analysis of price determinants reveals that, unlike in advanced economies, the dynamics of price changes in Nepal are influenced by more than just the interactions of money supply and aggregate demand.

As several studies show, Indian price level is an important determinant of Nepal’s inflation as the country imports over 60% of its goods from India and has a limited production base. From final consumer goods to production inputs, Nepal’s economy is deeply reliant on imports from India, which leads to the transmission of price changes. Simply put, Nepal ends up importing India’s inflation. The old saying that ‘Nepalis have to put on an umbrella if it rains in India’ is not there without a reason.

Another driver of inflation is high production costs. Increases in the prices of oil and non-oil commodities, both on the international and domestic markets, contribute to cost-push inflation by raising production and distribution expenses. This is particularly true for essential inputs like fuel, which have no substitutes.

The quality of economic infrastructure also affects cost dynamics. Nepal’s different economic sectors, whether agriculture or industrial, all operate under an inefficient economic system —which fuel upward price pressures. Poorly developed infrastructure, from utilities and production processes to supply chains and poor labor markets (unavailability of skilled and semi-skilled labour), stifles efficiency, limits productivity, and inflates production and distribution costs. As a result, the economy struggles to break free from a cycle of rising prices.

When one thinks of cost-push inflation in Nepal, the high-cost environment may just boggle the mind. The fuel prices are rising, land prices are unimaginably high and construction materials don't come cheap either, which has created inflationary pressure on the rental market (rent prices of retail spaces for housing and businesses) due to housing price bubbles and high construction costs. For businesses, it results in bigger spends and a dilemma over business sustainability.

Similarly, funding gaps can force producers to stick with obsolete plant and machinery raising production costs and obstructing firms from efficiency gains and economies of scale.

In any case, the producer will either perish eventually or survive by passing on the costs to consumers.

Unchecked profit maximization deeds such as price gouging under different pretexts (for instance, prices go up in advance when dollar appreciates against rupees even when their effects may take time to occur in the local economy; unchecked price gouging during festive seasons, or the undetectable practice of price collusion by firms) are other source of inflation.

Also, the market consists of depraved forces such as cartel and syndicate and monopolies and their different variants, whose control on prices, by impeding competition or price-fixing, have become insurmountable. They have prevailed because Nepal has one of the weakest competition policy frameworks (or, lack of it like antitrust policies) while its governments lack the intent and capacity to enforce consumer welfare, all of which is heavily influenced by the country’s overall political economy. Clearly, market players have championed at forging collusion and forming barriers to entry and perpetuating them.

The role of middlemen/traders in controlling vegetable prices during the distribution process from farmers to consumers, longstanding syndicate in transport sector, fuel dealers’ cartel, obstruction to foreign investments under the pretext of safeguarding domestic and infant industries (during the recently announced FDI policy on agriculture sector, different agricultural associations came together to resist the decision) or the duopoly (as seen in the country's telecommunication sector - Nepal Telecom and Ncell) is aided by weak enforcement of market regulations that make it competitive.

The resulting synergy prevents competition, efficiency gains and fair market practices to control prices, which also explains their role in building the high inflation environment. The prevalent market conditions play an influential role in shaping consumers' inflation expectations and economic behaviours.

In absence of strong consumer welfare and protection mechanisms, complacency has seeped through the psyche of average middle-class consumers and the segment beyond as they lean to believe that they can do nothing about it despite everything getting costlier by the day. As a result, consumers are forced to become submissive price takers. As inflation normalises in consumer psychology, inflation expectation usually tends to be at the higher end, allowing further inflation to set in.

In recent times, from fiscal year 2016/17 – 2018/19 (see table below), inflation was at one of the lowest levels. Yet, ask any Nepali consumer, they are more likely to respond that prices are getting more and more unaffordable, and that official figures don’t reflect their actual experiences. Food prices or restaurant menu price, rentals or assets price, and overall ill-practices prevalent in the market have shaped these experiences.

What would you do when your inflation expectation is on the higher end?

Perhaps, raise the price of what you sell.

But in a grand scheme of things, which is the economy, will each individual economic agent setting fire to that cycle help?

Inflation matters

Price rise affects businesses, consumers, investors, savers and salary and wage earners alike because it erodes the purchasing power of income (real income). In this sense, inflation can be considered as an indirect taxation on income.

A 10 percent fixed income on government debentures or bank fixed deposits (for instance, commercial banks’ fixed deposit rates and average inflation over the years has remained almost the same) for a retiree or a similar rate of return for businesses or long-term investors is zero in real value if prices are rising at the same rate.

Think about export businesses. Inflation not only diminishes external competitiveness (exports), but also discourages domestic producers because inflation makes their final goods and services dearer than cheap imports. This economic phenomenon at the firm-level leads to economic implications like widening of trade deficits and stress on balance of payments, resulting from producers' inclination towards trading rather than (re)investing. In fact, with the astounding scale at which land prices have grown in Nepal in the last two decades, economists believe there has been large reallocation of investments into lands and buildings.

Inflation is most brutal for average wage earners and low-income segments, particularly when food price shocks hit, as their share of food consumption in their overall household expenditure is relatively higher. While the rich may easily adjust with the high prices as their wealth grows at a larger proportion, the inflation effects amplify for the poor.

At the macro level, resource allocation becomes inefficient when prices rise. For example, when the cost of construction materials increases, government projects experience cost overruns. It's important to note that the government is a major spender in the economy. Every time a government project is delayed (a recurring issue in Nepal due to low capital spending), the time delays distort resource allocation as inflation continues to affect the costs.

For all these reasons, high inflation is detrimental to any economy.

Despite the extent of its potential damages, Nepal has a history of high inflation.

Inflation stood at an average of 8.8 percent between 1973/74 – 2009/10. Average food price inflation was 9.2 % in that period.

Graph 1

Accounting their compound effects, if a household afforded 100 kg of rice (one of the typical basket components of Nepali consumers) at a price of NRs 100 in 1972/73 (a hypothetical price), it would cost NRs 2,223 in 2009/10 — an accumulated inflation by 2,123% in 37 years.

So, if your grandparents had saved some 2,200 rupees back then in a pouch and buried it underground somewhere in the backyard, a whole lot of fortune for that period, you’d be highly disappointed today (unless they are antique banknotes and coins) — it won’t fetch you more than 100 kg in the present time (adjusted to 2009/10). Has your income grown adequately that could negate the effects of inflation?

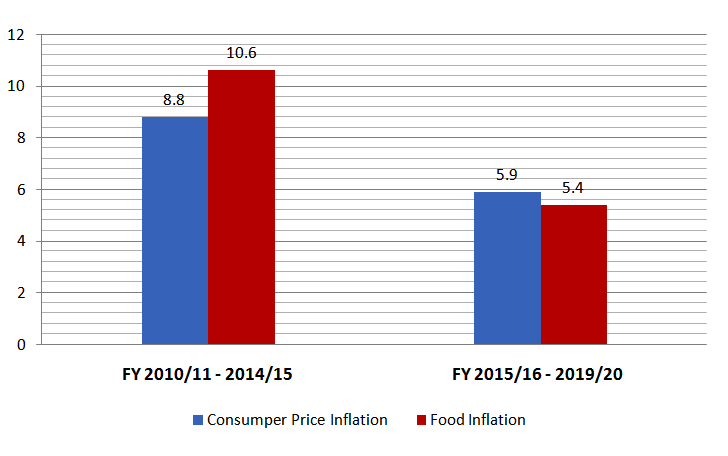

The trend of inflation hasn’t changed much after either, except for recent years’ slide which is expected to rise again. Between 2010/11 to 2014/15, prices grew at 8.8 percent while food inflation was a whopping 10.6 percent (see chart 2). It moderated in the second half of the decade (2015/16 - 2019/20) with consumer prices growing at an average of 5.9 percent and food inflation at 5.4 percent.

Graph 2: Inflation Rate in the two half of the decade of 2010

Going by the history of inflation in Nepal, households, consumers and businesses have long tolerated the brunt of inflation through base effect on prices. Combine that with high cost of capital (borrowing rates) and average Nepalis’ weak income level, Nepal’s economic scene gets murkier.

Interest rates

Interest rate is another crucial economic variable that affects economic decisions. It is the price/cost of borrowing — one can consider it as interest inflation. Unlike general inflation, high interest rates have regularly attracted scrutiny and criticism from different economic spheres probably because at some point of time, personal and business finances fall back on debts. Debts are usually long-term and their effects are pernicious if you’ve borrowed at higher rates.

Industrialists, entrepreneurs and hydropower investors get worried when borrowing rates are high because projects depend on bank financing as much as equities. High interest rates not only make projects less feasible due to high costs but also unattractive due to cash flow and profit concerns. Just as inflation, it can also distort the overall economic landscape.

High interest rates contribute to inflationary pressure. Interest is overhead for businesses. As such, it is passed on to consumers affecting prices and high inflation is bad for the economy.

High cost of borrowing also deters consumer spending. When consumer financing becomes costly combined with high inflation, consumers would rather defer their spending and choose to save. As aggregate demand falls, businesses lose confidence.

It is quite intuitive that, at present times, making borrowing cheaper creates more economic incentives than allowing it to float at some sub-optimal range.

Low-interest rates incentivise businesses to start, grow and expand business activities. For investors, it gives much-needed confidence to undertake long-term and capital-intensive projects, which means more job opportunities and hiring.

Nonetheless, lowering interest rates doesn’t automatically lead to good investments. Low interest rates can induce investors, firms and even consumers to overindulge and borrow in excess, take higher risks and make speculative or unproductive investments. Cheap credit can stimulate asset bubble and import-based consumption (for instance, personal vehicles and fuel and luxury items) and even create inflation with artificial demand surge.

In the past, Nepal has experienced what cheap, unplanned and unregulated credit can do. The real estate bubble during the mid 2000 and Kathmandu’s urbanisation fiasco that has its roots in cheap and unsupervised credit to the real estate sector is a prime example. Although credits were as high as eight percent and above, investors still viewed credit rates as cheaper because during the asset bubble, opportunity costs — the real estate investment gains — were substantially larger.

Nonetheless, in the backdrop of this widely accepted economic thinking about low-interest rate as economic incentives and currently in fashion in the advanced economies post 2007/08 financial crisis, how does Nepal’s bank interest rate compare?

Table 1

In the last eight fiscal years from 2012/13 (2069/70), average lending rate of commercial banks (‘A’ class according to the central bank distinction) is 11.1 percent (see Table 1).

Table 2

Interest rates weren’t low prior to that period either. Rates for agriculture, industrial and commercial loans were all expensive (see Table 2). In the nineties, lending rates were as high as 18.5%, the least being 14.25%.

Until not so long ago, banks were charging separate fees for documentation and processing services that further shored up the borrowing cost, now streamlined to one fee head — somewhere around 1% of loan value, still a considerable additional cost for borrowers.

Development banks and financial institutions classified as ‘B’ and ‘C’ class institutions, the other categories of BFIs, are only slightly distinct in functions but serve the same market segment under similar norms as the commercial banks. Their lending is costlier and usually criticised as imprudent.

At the same time, banking processes are onerous for ordinary to organised borrowers. Central bank reports that it takes some 38 days for the majority of the SME borrowers to receive loans, at an average of 12.51% interest rate and one percent service charge.

Moreover, accessing loans, almost mandatorily, require fixed assets as bank collateral — land and building of course. Banks hardly provide loans based on cash flow or movable assets such as plant and machinery or based on project financing.

For businesses and individuals who have ideas and enthusiasm, these high capital and transaction costs are deterrents to doing business, create funding gap and compel them to look for expensive alternatives (the good news is that, in recent time, there has been emergence of alternative source of fund like private equities but is at nascent stage and aren’t available for all types of borrowers).

Even if they overcome all the hurdles, it would be unintelligent to expect that businesses would maintain ethical integrity after all those trials and tribulations of doing business in Nepal. How would businesses recoup all those extra costs?

Firms and individuals may resort to unfair business practices like colluding and hiking prices, evading taxes, underpaying staff or compromising on product quality in order to maintain high profitability and beat inflation. It’s a natural instinct but one where society will have to pay the costs for, unlawful too and not without some ounces of greed behind it.

Who do small borrowers resort to?

For low-income segments that are not catered by the top tiers of the BFIs, microfinance institutions (MFIs) and saving and credit cooperatives (SCCs) have emerged as effective lenders providing collateral free small-ticket loans.

MFIs who fall under the purview of NRB as ‘D’ class institutions receive loans from the rest of the BFIs at subsidised rates. According to the central bank, 90 MFIs are currently providing microfinance services in Nepal with their 3,629 branches having presence at 580 local units.

MFIs that are supposed to serve the unserved and underserved low-income people provide financial services at exorbitant lending rates, often viewed as exploitative. MFIs were found to be lending as high as 30 percent interest rates, according to critics and media reports.

In 2017, NRB put a lending rate cap at 18 percent barring 2% service charge. The recent monetary policy reduced the cap to 15 percent.

Interestingly, MFIs are investors’ darling at the stock market as they rake in handsome profits and distribute attractive shareholder dividends. They profit by mobilising high-cost debts and maintaining a high spread of up to 7%.

52 MFIs are currently listed in Nepal Stock Exchange (NEPSE).

On the other hand, SCCs, that are part of a broader cooperative model which is recognised as one of the three pillars of the national economy, are member-based organisations and regulated by the Department of Cooperatives.

According to the department, 34,512 cooperatives operate in Nepal out of which there are 13,578 SCCs and 4,371 multipurpose cooperatives, both allowed to carry out basic banking functions.

In fiscal year 2073/74, their deposits amounted to Rs 280.75 billion with credit portfolio at Rs 242.26 billion, up by 143.5% and 113% respectively in a matter of five years.

Similar to MFIs, SCCs are also found to be charging exorbitant interest rates to their members, levying up to 25 percent taking advantage of weak regulation and monitoring. Their lending rate was capped at 16% in mid-2019 — which was only recently reduced to 14.5%.

Unlike MFIs, cooperatives aren’t completely driven by dividends. Yet big cooperatives, mostly urban based who have a strong deposit base and large lending size, are found to have misappropriated funds, lent too leniently and recklessly and made large investments in the volatile real estate market.

So far, 12 Kathmandu-based SCCs have already been identified as financially problematic while authorities believe the number can rise considering how some cooperatives had been playing fast and loose.

There’s little doubt that MFIs and SCCs have expanded financial access and provided respite to small borrowers, but the high-cost debt model can’t really be productive and sustainable in the long haul. There is little evidence about their effectiveness in creating sustainable markets and reducing poverty. Instead, they can push the poor section into debt traps, as the poors lack adequate skill and knowledge on financial management and about the effective cost of such loans.

Takeaways

The main takeaway is that whether big-time businesses and industries or MSMEs, middle-class consumers or small-ticket borrowers — all of them operate under a financial system that is predicated on a high interest rate environment. That makes everything costlier and even financially risky.

When credits are so expensive and unfairly accessible, it locks investment and entrepreneurial potential, often pressurizing the government to do something like mobilising subsidy programs. Governments, then, carry fiscal burdens with a cash-strapped treasury. These burdens can be avoided considerably if bank rates can be steadied at optimal level.

For instance, currently, the government runs 5% interest subsidy programs aiming mainly farmers and youths and other beneficiaries. In the fiscal year 2018/19, the government paid Rs 1.25 billion as interest concessions, says the monetary policy 2019/20 while the current macroeconomic and financial situation report published by the central bank for 2019/20 reports that Rs 59.56 billions were extended as concessional loans to some 32,448 borrowers. These programs are aimed at agriculture and livestock businesses, youth self employment, women entrepreneurship, migrant returnees and even higher education loans.

Suppose, if bank rates can be lowered, the fiscal burden arising of subsidy programs could be cut down too. Say, if lending rates can be steadied around 7%, subsidy rate could be lowered, probably halve it. The savings can, instead, be invested in other critical rural infrastructures.

If lending rates are to be adjusted, detractors may raise concerns about saving shortfall since saving rates will have to fall too. Nonetheless, in light of the arguments this piece raises, it makes better economic sense to clamp down on the prevalent high interest rate structure and high inflation to reform the economy.

In advanced economies, inflation and interest rate are the major policy targets and tools respectively. Whether the Fed, ECB or the BoJ, they constantly monitor inflation and lever interest rates as the policy tool to ensure price stability and prevent economic hardships for both consumers and businesses. ECB and BoJ have even experimented with negative interest rates to achieve their inflation target of 2%, which they view as optimal and unthreatening to nominal income.

In Nepal’s case, NRB’s handling of interest rate as the ultimate tool alone won’t shake inflation. Other authorities and mechanisms should function firmly with concerted effort in reinforcing market competition and consumer welfare.

In comparison with Nepal’s inflation and interest rates, where does Nepalis income level stand? Does the income at their disposal allow them to cope with rising prices, access bank loans easily and can they afford the interest? Can their income level push market confidence?

The dismal income level

When we think about our income, we usually feel poor. This is because first, with whatever is at our disposal, it can buy a lesser amount of goods and services, thanks to inflation. Second, our income level is actually too low.

Nepal’s average per capita income is $1,090, based on GNI per capita in 2019, which was $960 in 2018. The recent surge pushed the country up to lower-middle-income country status in the World Bank classification, but that rise is likely to last short due to the ongoing pandemic effects.

According to the Nepal Labour Force Survey (NLFS-III), the national average earning of Nepalis is Rs 17,809. Going by the poverty headcount ratio in 2019, according to the World Bank, 8% of Nepalis were earning less than 1.90 dollars per day while 39% were earning less than 3.20 dollars. Those ratios were 15% and 59% in 2010. This is a straightforward overview of Nepalis income level.

How have salaries and wages changed over the years?

Annual government surveys reveal that wages have changed significantly over the years but salary indexes have failed to make considerable strides. In the graph below, the wage index represents nominal wages for construction, agricultural and industrial wages while the salary index comprises private and public sector salaries.

By and large, gains made by salaries have only been modest, which are negated by the rise in overall price level (CPI) and food price level (FPI). Wage index, mainly agriculture wage has made real gains, both in terms of their individual rise and when adjusted to inflation.

Let’s examine these wages and salaries closely and compare them with respect to their ability to transform markets?

Government Salaries

Government employment is believed to be one of the few secure jobs in Nepal, but is their salary scale sizable enough to build market confidence and boost spending?

A 2016 study commissioned by ILO shows that the average salary in the public sector is Rs 15,904, estimated from a sample of 154,518 employees, which is close to the national average earnings.

During a conversation with two mid-level government employees, one in civil service and another in defence, they conceded that while government employment provides job security, their salary is peanuts, depriving them of any cushion to make any extra or even essential spending at times.

One respondent, presently Captain in rank at the Nepal Army, said that his current salary scale is Rs 39,050 (excluding grade pay) even after 10 years of service beginning from the rank of lieutenant. Six years ago, his salary was Rs 26,470.

Some 200,000 personnel serve in the security force (Nepal Army, Armed Police Force and Nepal Police) alone where their salary ranges from 20,778 to 69,482, with Nepal Army’s Chief Commander earning the highest pay.

Another respondent, currently a section officer in civil service, has a similar salary scale. Married and a father of a child, he shares that he often experiences anxiety on how to cope with Nepal’s skyrocketing inflation and manage modern day and future needs and wants. Presently, civil service employs 88,758 personnel.

A part of these salaries is deducted as taxes, a portion goes on retirement savings. Spares will have to cover food, clothes, housing, water, electricity and internet bills, healthcare, waste management and transportation. For couples with children, expenditure patterns are drastically different as additional expenses arise with education and medical bills. Factoring these expenses, the public pay gap is — astounding.

Can low-ranking staff from Nepal's rural and remote regions ever hope to achieve upward mobility with the current pay gap? Will government employees and the working class truly be able to afford simple pleasures—like dining out, taking a family vacation, or enjoying occasional recreation—under the existing economic conditions?

Truth to be told, a decent family vacation and recreation are alien concepts to many. The two respondents shared that while they aren’t too frugal — they have observed that people within their work circle repress spending to great extent — because they can’t afford it.

Some believe that government employment provides reliable future security through pensions and peace missions for security force personnel. True, but it would be fallacious to think that such one or two-time lump-sum payout is enough to provide future financial security, cover household needs, modern day wants and also save enough to build housing for themselves someday — a customary Nepali household dream.

There is general disregard for inflation, difference between present and future consumption (intertemporal consumption), quality of life and frequently occurring lump-sum overhead out of social and medical obligations and existing high asset prices and lack of affordable or low-cost housing options (in fact, the concept of it).

Private sector salaries

Remuneration packages aren’t better inside the private sector either — with strong dissatisfaction surrounding the pay scale.

According to the ILO study, the average basic salary in the private sector is Rs 17,085 averaged from a significantly smaller sample of 7,782 employees.

To some extent, undeveloped markets, skill and qualification gap and low productivity explains the meagre pay checks. For instance, four out of five people in Nepal’s workforce don’t have secondary education, says NLFS – III.

However, it doesn’t permit employers to underpay workers and withhold and even deny payments, an exploitative practice that has tarnished the private sector and market economy philosophy.

Until July 2018, monthly minimum wage was Rs 9,700 (around 85 dollars a month at current exchange rate) which was then raised to NRs 13,450 (around 115 dollars) while the minimum wage for tea estate workers was set to Rs 10,781 (around 93 dollars).

Low and delayed payments to private hospital nurses, private security workers and media journalists and sometimes even denial to compensate, for instance, the ongoing sugarcane farmer protest against the sugar mill owners, are some representative cases but not one-off.

70% of industrial workers were denied full salaries for the month of Chaitra (March-April) after the first hits of the global pandemic were observed in Nepal during Chaitra, says a survey by Whole Industry Trade Union Nepal (WHIN) that covered 219 industries in its study.

These notorious business practices are longstanding, widespread and suggestive of an inherent tendency to exploit labour and skill at every opportunity. Moreover, they kill the spirit of workers, and make them defensive with their spending habits as the social security system is absent for almost all of them.

So far, only public employees are covered by the social security scheme as pension, while the government has recently come out with a plan and resolve to provide the coverage to private sector employees as well. Workers in the informal sector who make up 62.2% of the total labour force employed (7.1 million) have no social security coverage.

Banks and insurance firms

Banks, mainly commercial banks, and insurance firms, are perhaps the most rewarding and secured job providers within the private sector. Commercial banks have evolved over the period and restructured their remuneration schemes greatly. Incentives such as bonuses from profit, performance allowances, and annual paid holidays have further enhanced their career attractiveness.

In view of their balance sheet size, BFIs can do much better with employee payouts, if the industry really prioritizes talent, productivity, retention, and their own growth prospect, believes an industry insider.

With around 10 years experience in the industry, the A class banker who wishes to remain anonymous, shared that while salaries and benefits are better than other industries and professions, it would be unwise to think it is reassuring. “The salary is spent to meet several household needs, and supports a certain standard of living, but leaves even mid-level employees at a tight spot when it comes to thinking beyond an average living standard and future financial security. Just look at the market price graph. You can imagine what it can do to the young workforce, those who have different perspectives on life and ambitions.”

For undergrad entrants, industry average salary at ‘A’ class industry usually starts at approx. Rs 17,000 while a graduate who enters the industry workforce as management trainee (MT) begins with somewhere around Rs 30,000. Probation period, for both type of workers, is six months to a year.

The sector is also rampant with complaints of long working hours, extreme work pressure and nepotism and favouritism in employment and career growth, which is pervasive across other industries as well. “If you monetise those costs, the current salaries don’t really measure up and this is prevalent across entire sectors in Nepal”, the banker shared.

An employee at an insurance company, currently working as a driver there, shared that he and his wife compromise on their several needs to provide for their family of 6, including three children and an ageing father. “Born in the hills of Ramechhap, existing opportunities didn’t fetch enough to make a decent living, so I moved to Kathmandu a long time back. After 11 years into the service in an insurance firm, I currently earn a salary of Rs 30,000 (approx. 16k basic + 14k allowance), all of which goes to children’s expensive education needs and our minimalistic existence”, he shared. “Apart from my day job, I moonlight as a freelancing driver to make some additional income, just to make it to the safe side in the future.”

Even private sector industries like banking and insurance which have financial prowess to reform their industry-level remunerations and influence and create ripple economic effects contain salaries as part of their business strategy. Other private sector players are simply reluctant to share their fat earnings. We can assume this based on their level of transparency, overall employee grievances and several reporting on the subject matter.

At the government sector, they resist raising salaries fearing that it may send inflation over the roof, fiscal stress may become insurmountable and increased pension liability may doom the future. Public opinion is also harsh about raising salaries because they believe that government employees and institutions are one of the most inefficient and corrupt forces in the country.

The bottom line is wages and salary level is considerably low in Nepal to allow living a decent, dignified and drudgery-free life, although the increment in the salary and wage index show a different picture contrary to the lived experiences.

The situation begs the question: Can markets develop; consumption boom and investments thrive with stagnant wages and salaries that leave little money at the hands of consumers for spending?

If earnings are really low, what’s with the people’s lifestyle?

On the surface, the earning level may look extraordinary when ‘extravagance’ observed in social media is measured and compared. Even analysts paint with a broad brush that Nepalis live more than a decent lifestyle, ignoring the fact that it is predominantly an urban phenomenon where individuals live in joint families sharing household resources and inherit property (land and/or house) later in the future. Remittance income and high-interest personal mortgages are other two sources contributing to managing finances for such occasional 'lavishes'. This explains a part of the divide, and about the middle class.

Prominent reasons that explain the starker divide and excess consumption (most stark example being the extravagant wedding celebrations) than the average suburb residents and within the same geographic cluster are historic land inequality, simplified access to loans, the sharp rise in land prices, and an increasing informal economy that benefits few at the expense of many. The latter two boomed greatly post-2000 while the widespread corruption in the Nepalis economic system is no secret, all of which have raised the number of nouveau riches.

Their everyday way of life, however, do not speak for what goes in the lives of the rest of the average workforce who has to juggle their paltry income on various household budget heads while inflation remains razor-sharp for them (bear in mind, inflation is more biased and detrimental to the low-income segments) while pay check rises are sporadic and small.

Creating a fine balance between interest, inflation and income

In today's economic landscape, a combination of high borrowing cost, high inflation and low income is nothing short of a deadly combo leading to an unfriendly business environment, weak domestic consumption and poor living standard — a recipe for a sustained weak economy.

For the economy to thrive, consumer demand must rise. Increased demand stimulates production, unlocks private investments, and accelerates economic growth. But this cannot happen unless real incomes rise, inflation remains under control, and interest rates are set at sustainable levels.

While inflation and interest rates serve as stabilising tools in any economy, the income side of the equation represents a deeper, structural issue. Simply relying on stabilisation measures will not be enough to shift the course of the economy facing such profound challenges. What is required are bold, structural policies aimed at revitalising demand and reinvigorating the economy—policies that go beyond short-term fixes.

Clearly, one of them is revamping stagnant government salaries (public sector wages) and reforming and restructuring the public sector. While the idea of raising government salaries may seem an artificial solution and taxing on public finance, it is actually long overdue considering the pay gap which reflect the government's disconnect from economic realities and the fact that the sector is rather allowed to fester with corruption, inefficiency, politicisation and resistance to reformations. The public wage reform should be part of a broad restructuring that prioritises performance and productivity in public service delivery.

The reform would not only enhance the financial stability of government employees, but also trigger broader economic benefits. For example, increasing their purchasing power could boost domestic consumption. As one hotelier in Chitwan observed, private bank employees flock to tourist destinations like Sauraha and Pokhara along with their friends and families during long holidays, spending on leisure and recreation, and may spend more if Sundays were holidays too. A similar pattern of consumption could emerge among lower-ranking public employees, but only once their financial security improves.

Larger gains are possible if such spending is tied with the domestic production. For instance, both government and the private sector can introduce alternate (to wage hikes) or complementary benefits like family holiday coupon system, as employee wellbeing programs, reimbursable at any relevant MSMEs across the country and administered by local administration.

The private sector can also play a role by enhancing employee well-being programs. Banks, insurance firms, and major institutions could offer fitness memberships or subsidized transportation benefits, particularly if public transport infrastructure is improved. These initiatives not only promote healthier lifestyles but could also stimulate job creation in related sectors, such as fitness centers and public transportation. This is just one example.

Public wage reforms can also induce spillovers on private sector salaries and employment through a signalling role. For example, private companies might be inspired to adopt wellness initiatives similar to those introduced for public sector workers.

Addressing these issues is crucial in shifting economic psychology. Unless price stability is ensured, real income is raised and costs of capital are reduced, it would be impossible to change business, investor and consumer psychology that is clouded by long-lasting pessimism and more so with the ongoing pandemic. If the government and its machineries continue to allow repression of economic desires, the economy will continue floating into abyss.

Read More Stories

Kathmandu’s decay: From glorious past to ominous future

Kathmandu: The legend and the legacy Legend about Kathmandus evolution holds that the...

Kathmandu - A crumbling valley!

Valleys and cities should be young, vibrant, inspiring and full of hopes with...

Today’s weather: Monsoon deepens across Nepal, bringing rain, risk, and rising rivers

Monsoon winds have taken hold across Nepal, with cloudy skies and bouts of...