Hiti | Architecture | History | Legacy | Engineering | Licchavi | Malla

This work started a year ago when my editor approached and enquired if I knew about the hiti. Hailing from the very community that introduced the word, I immediately responded, “Of course…” with a sense of pride. It was after I started the assignment, I realised how little I knew.

What started as a simple ‘of course I know’ quickly turned into deep curiosity, evolving into a passionate quest to truly grasp the depth of this ancient marvel.

It’s a well-established tale amidst us — the still enchanting and mysterious Kathmandu Valley was once an immense lake (Taodhanahrada) ages ago. According to the Buddhist version, Bodhisattva Manjusri in Treta Yuga drained the water from the lake forming Kathmandu Valley. Only a few are aware there is a Brahmanical version too — that it was submerged again and either Narayan himself or Krsna (Narayan’s eighth avatar) drained the valley for the second time paving the way for the civilisation to flourish.

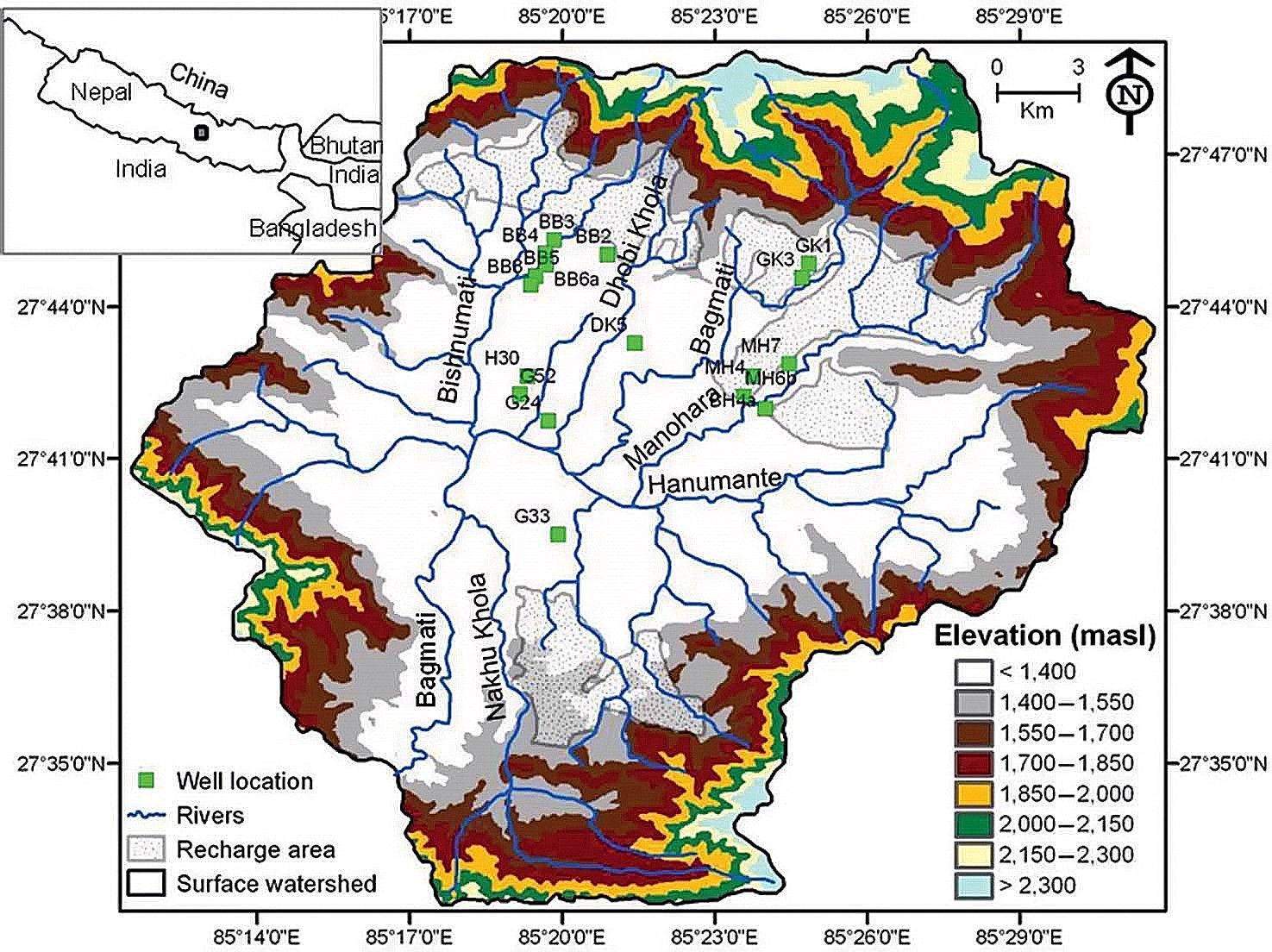

The valley’s arable terrain, the gushing river and favourable climatic conditions welcomed bands of settlers to rejoice swiftly. The vale now extends about 25 kilometres from east to west and is about 19 kilometres at its maximum width.

Fast forward, under the reign of different monarchies — notably Licchavis and Mallas — the Valley flourished in art and architecture through the exceptional skills and knowledge of the indigenous people who made the most of the geographic layout and the natural resources at hand.

Grand structures — royal palaces, temples, monasteries, and stupas — reached their pinnacle, with each monument reflecting its religious conviction, dedication, and the rivalry at the time between cities to beautify their respective cities through magnificent craftsmanship. Its cultural significance today is the outcome of an extraordinary cultural explosion and growth then.

“It is within its confines that generation after generation of artists and scholars, priests and monks, have lived and worked — inscribing on stone, metal, and paper the record of their passing; raising glory after glory of temple and shrine; and shaping in stone, metal, and paint the infinite forms of the gods. For the gods, too, have especially preferred Nepal Mandala as their dwelling place.”

- Dr. Mary Shepherd Slusser in Nepal Mandala: A Cultural Study Of The Kathmandu Valley

One prime testimony of their outstanding virtuosity is hiti — the earliest, meticulously fashioned water supply system that provided the inhabitants of Kathmandu Valley with fresh water for centuries.

What is hiti?

The word ‘hiti’ — generally understood as ‘Dhunge dhara’ (stone spout) in the Nepali language — comes from the Nepal Bhasha, meaning ‘tap’ through which the water flows unperturbed being devoid of a stopper.

The understanding of hiti, however, shouldn’t be reduced to a mere ancient stone faucet. It rather represents a whole intricate system with diverse components working together to bestow the desideratum of life — water. They boast history, science, and craftsmanship, among others.

The History

The original annal history of hiti can be traced back to the Lichhavi era.

‘The Gopalraj Vamsavali (1985)’ — a facsimile edition of the late 14th century book which extensively chronicles different dynasties — by Dhanavajra Vajracharya and Kamal P. Malla in its Folio 20 mentions ‘a stone water-conduit was constructed’ by the Licchavi King Vrsadeva at Sinagum Vihara (Swoyambhu). However, it doesn’t get into the exact date of its installation.

The Hadigaon inscription from 472 Mandeva Sambat (which would be 607 Bikram Sambat or 550 CE) makes reference to a stone spout built by Bharbi, grandson of Licchavi King Mandeva.

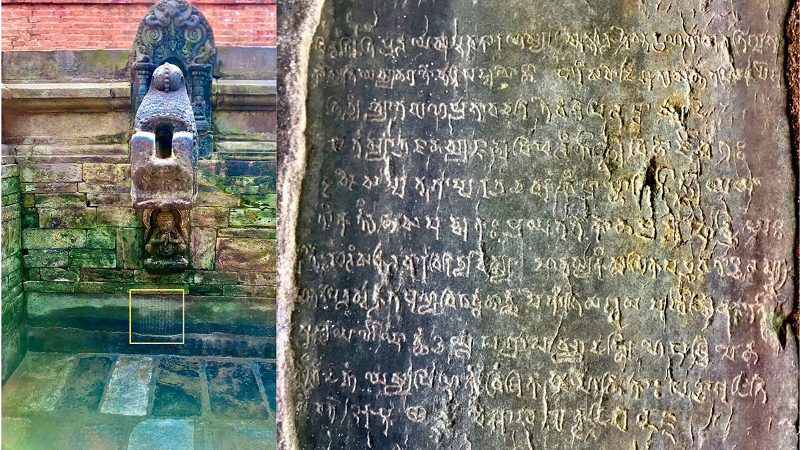

The celebrated Manga hiti (otherwise known as Mani dhara or Jewel Fountain) in Mangal Bazaar, Yala city is the oldest functional existing stone spout. At the base of its left spout (now under the water), a horizontally etched stone column mentions it being consecrated by Bharbi in 492 Mandeva Sambat (570 CE).

These hiti, however, are believed to have existed prior to the Lichhavi era — perhaps already in the Gopal or Kirat era.

During the early Licchavi era, the stone spouts were referred to as ‘Kirti’ meaning ‘merit.’ As only the opulent class could lay such owing to their exorbitant building, those who set them were believed to be blessed by Gods.

Kirti was later renamed to ‘pranali’ meaning ‘method/system’ in the late Licchavi era, and then ‘hiti’ during the Malla era.

The astounding hiti system was built throughout the reign of the Licchavi era, which peaked during the Malla era.

The Science

Hiti system is an application of practical hydrological science and can be considered an advanced engineering prowess of the past.

It harnesses gravity to channel the water and has a systematic flow control to regulate the amount with an advanced drainage system to prevent blockages, and water filtration and waterproofing practice.

Dr. Mary Slusser (in her book Nepal Mandala) and Prof. Sudarshan Raj Tiwari (in his paper) explain that in lieu of inhabiting flat and fertile land, the earliest permanent human (Kirāta) settlements called Prn or Pringga over the Kathmandu Valley rim — Kirtipur, Gokarna, etc. — were in the highlands (tar) and the steep slopes. This was done to shelter themselves from submerging during a deluge and to utilise the comparatively more arable flatlands nearer to the rivers to harvest better agricultural produce.

That being the case, people residing in these regions either had to bring water from higher elevations or depend on underground water. This necessity for water perhaps led to the innovation of the hiti system.

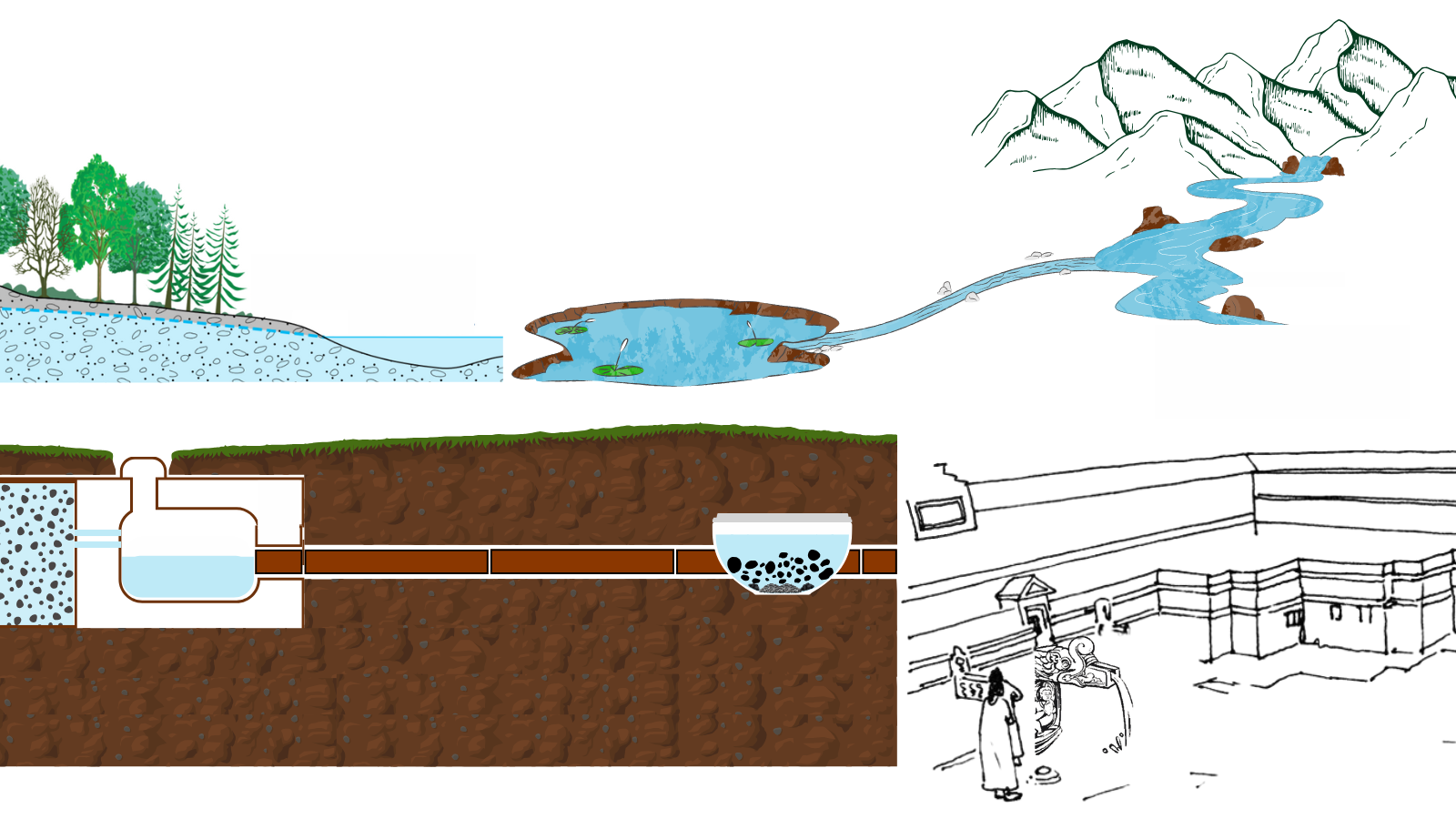

In his book ‘Hiti Pranali’, Padma Sundar Joshi explains elaborately, how a complete hiti system that encompasses nine different components functions:

Rajkulo (Royal Canal)

Originating from the foothills, a Rajkulo (de:dha) serves as a water canal that channels water from a distant perennial river to a pond. Then the water is directed to the respective destination — much like modern water transmission pipelines. The canal was also designed in a manner to dispense water for irrigation along its route and collect the surface water.

All the significant hiti within the Kathmandu valley have connections with age-old Rajkulos.

The very first Rajkulo is said to have been laid at an ancient Newar town — Sankhu, in the 5th century by the Lichhavi King Shankar Dev to avail drinking water and irrigation to the people of the city.

Bhaktapur’s first Rajkulo is said to have been built by Queen Tula Rani, according to the Licchavi-era inscriptions in various hiti of Bhaktapur. The canal system likely expanded during King Jitamitra Malla’s reign.

The Rajkulo in Lalitpur started during the reign of Lichhavi King Sivadev and Amshu Verma from Tika Bhairav around the 7th century.

The actual founder of Kathmandu’s Rajkulo is uncertain.

The Bageshwori Canal supplied water to Bhaktapur’s water system, the Tika Bhairav canal nourished Patan’s ponds, and the Budhanilkantha Canal to Kathmandu.

Today, only Patan’s Rajkulo remains, but it’s been pushed to the brink, an outcome of Kathmandu’s rapid urbanisation. The one in Kathmandu has vanished without a trace beneath the city. Bhaktapur shows a slim chance of revival.

Pukhu (Pond)

Ponds need no explanation. But depending on their location and use, ponds within the Kathmandu Valley can be categorised as — external and internal.

External ponds — strategically placed at higher elevations from the human settlements — were used to supply irrigation canals and to collect rainwater in the summer, enabling it to gradually replenish groundwater the rest of the year.

A few examples of external ponds in the valley include:

Bhaktapur — Siddhi pukhu, Bhaju pukhu, Nā pukhu

Patan — Lagankhel pukhu (defunct), Paleswan pukhu (defunct)

Kathmandu — Rani pokhari, Ikha pukhu (defunct), Lainchaur pokhari (defunct)

Internal ponds that are located in the settlements are relatively smaller in size and serve as a buffer against downpours during the rainy season, including recharging the groundwater, particularly local aquifers. Additionally, they serve practical purposes like washing and cleaning.

A few examples of internal ponds in the valley include:

Bhaktapur — Tekha pukhu and Khancha pukhu

Patan — Pimbahal pukhu

Kathmandu — Pako pukhu, Khecha pukhu

Padma Sundar Joshi in his blog explains, “The construction of a pond is a skillful engineering work requiring good knowledge of local hydro-geology. Traditionally, clay liners are provided with one foot or more of thick black cotton soil. The walls are constructed with dry brick masonry so that the groundwater flow is not completely restricted. This also releases the water pressure so that we do not need to build strong walls around the pond. These clay layers not only provide liners but also serve as a habitat for the flora and fauna that recycle the ‘nutrients’ of the pond, keeping it healthy.”

To prevent a pond from overflowing, it is sequentially linked to the strings of other ponds, and water is ultimately discharged to the river after irrigating the agricultural lands.

Shallow aquifer

About 30% of the freshwater on Earth comes from groundwater and can be found almost everywhere. The groundwater is naturally replenished by rain, snowmelt, and the water that seeps through the bottom of certain lakes and rivers.

The groundwater accumulates and forms ‘aquifers’ — a geological formation consisting of permeable material (sand, gravel, limestones, fractured volcanic, crystalline rocks, etc.) that stores significant quantities of water.

There are two general types of aquifers — shallow (unconfined) and deep (confined).

Shallow aquifers lie below a permeable layer of soil while confined aquifers have a layer of impenetrable rock or clay of varying thickness above them which are separated vertically.

The two aquifers present in the valley are separated vertically by a clay aquitard layer of varying thickness.

The hiti system gets its water from the shallow aquifers that are usually 3-5 metres deep from the surface level. It is believed these aquifers were discovered with the help of supernatural tantric wisdom.

Since the water content in aquifers mostly relies on rainwater, the water flow on hiti is minimal during the dry season compared to the vigorous flow during the monsoon season. To retain the constant flow throughout the year, the role of reservoirs, such as ponds, comes in.

Navi mandal / Infiltration gallery

A relatively small-sized Navi mandal (infiltration gallery), which serves as a water collector, is constructed in an ideal site near a local aquifer. Think of it as a mini tank for each hiti per se.

Navi mandal of varying structures can be found within the Kathmandu Valley whose design makes it virtually impossible for surface water [unfiltered] to enter.

Early in the days, only those who possessed Tantric wisdom were supposed to lay and see the Navi mandal.

Hiti du: / Water conduit

The water collected in Navi Mandal is piped through a series of underground channels — hiti du: — which are about 3 metres in length, 20 centimetres in breadth, and 15 centimetres in depth.

During the Lichhavi era, these water conduits were made of wood. Later, the Mallas used terracotta instead to ward off water leakage and xylophagy (eating of wood).

Hiti du: made of stone can also be found — mostly in regions with main streets to withstand its strain. The hiti du: of Nuga: hiti in Patan was made of stone to endure the ‘Ratha yatra’ (chariot procession) of Rato Machhindranath.

[In recent decades, steel and plastic pipes have replaced these old conduits.]

Hiti du: is then covered with gathu: chaa — a special type of adhesive and elastic clay — with a thickness of 15 to 20 centimetres.

The placement of hiti du: must consider different parameters such as water flow, topography, and elevation — demanding a high degree of skill and intellect.

To gush the water, gravity has to be harnessed — so the water conduit has to be placed from a higher elevation to a lower position.

If the hiti du: is placed at a slightly lower elevation, tiny debris may accumulate blocking hiti du: in a few years. If placed at a slightly higher elevation, the force of the water can erode the conduit.

How hiti were functional for centuries demonstrates the remarkable ingenuity of the engineers of the era.

Modern engineering estimates the critical and non-scouring velocities of water in addition to using a levelling instrument to assess the elevation of the ground to address these issues.

Athal and Water filter

En route to the spout, a bowl-shaped athal is often placed in between the Navi Mandal and hiti manga: at various apt locations to redirect the flow of water. An athal, covered with stone slab, is typically filled with layers of charcoal, gravel, and sand of varying grades for the further filtration of water.

Hiti ga: / The Basin

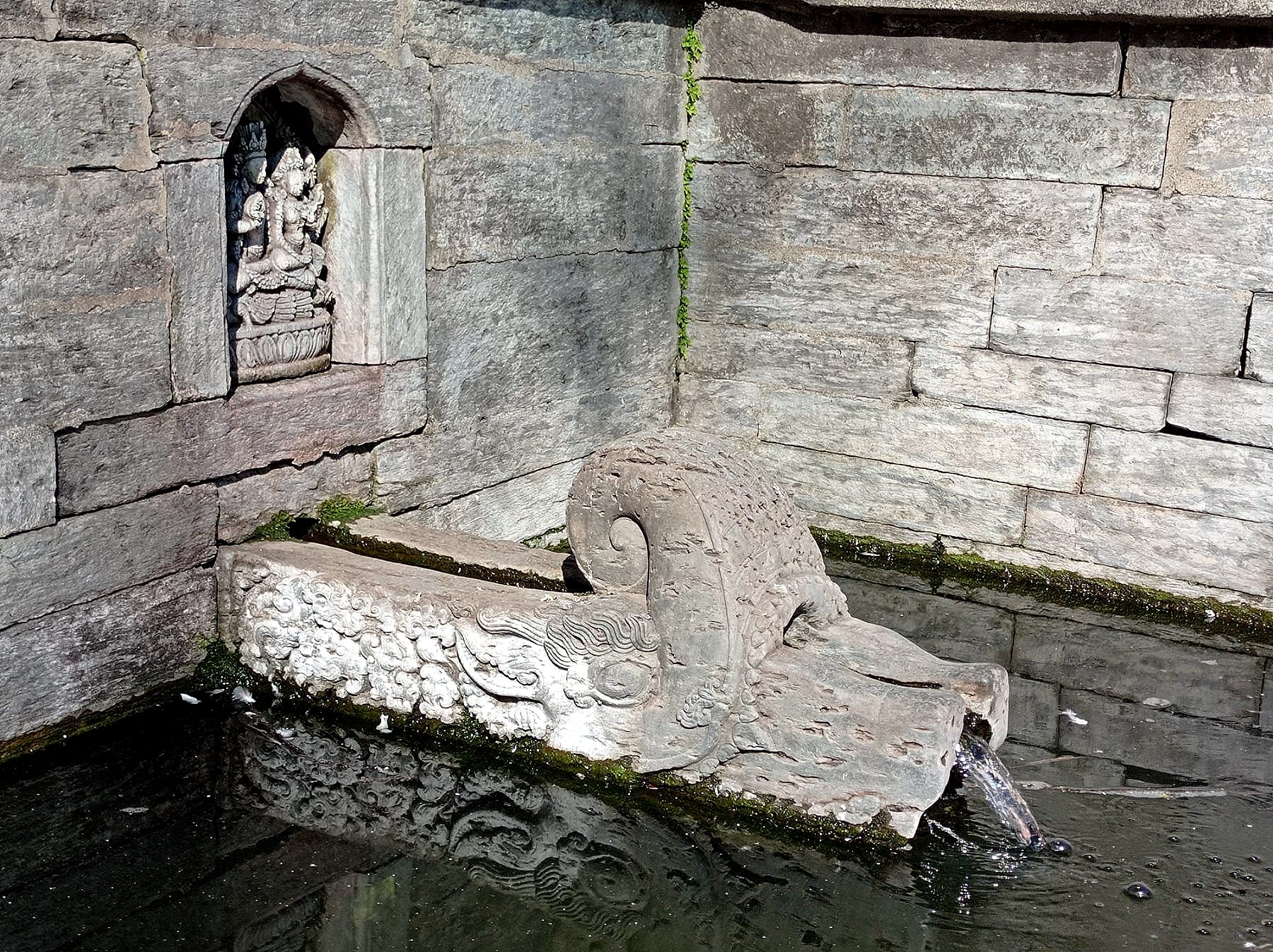

The conspicuous shallow pit region — hiti ga: — is the architectural attraction of the hiti system, which incorporates hiti manga: and hiti dhwo:

The base platform was normally paved with stone with side drains. A layer of kalo mato — a unique dense impenetrable black mud — was applied to the basin’s walls and bottom to make them waterproof to avert the seeping of water into the peripheral soil. The outlet drain was normally taken out of the settlement and used for irrigation.

The side walls are normally stepped with more than about a metre. These steps not only bring slope stability to the peripheral walls but also provide space for sunbathing and drying clothes.

In some cases, the wastewater was managed by allowing for the subsurface flow to charge downstream.

As a whole, the architecture of hiti ga: exemplified the power, opulence, and exceptional elegance of the Kings and their respective cities. The more intricate the quarter of hiti ga: and its hiti manga:, the greater the grandeur.

Hiti manga: / The Spout

The heart of hiti system — hiti manga: — is an architecturally embellished spigot of 150 to 275 centimetres in length.

It is usually positioned in the centre of one (or more) side walls, hanging down approximately a metre to facilitate easy water retrieval and taking a bath with convenience.

About 60-70% of the spout’s total length is embedded inside the wall for its reinforcement and stability.

Connecting the typically wood or terracotta-made hiti du: with hiti manga:, which is typically made of stone was considered to be a challenging task as improper connections could lead to water leakage. To prevent water leakage, the conduit and the spout were connected using wood.

The number of hiti manga: in each hiti depended on the rate of water flow and the number of water users.

Hiti dhwo: / Water drainage

To evade water stagnance in hiti ga:, a hiti dhwo: which serves as an outlet can be spotted at its corners. The main drainage route in hiti dhwo: contained holed bricks or iron-bar mesh that served as a filter and prevented drainage from being clogged.

The Beauty

The comely spout of hiti system is usually adorned with shrines, artistically arranged in symmetry, and intended to look to be protruding from a vertical wall.

The makara — a mythical creature with peculiar characteristics of an elephant’s trunk, a crocodile’s mouth, a wild boar’s ears and tusks, and a peacock’s tail — accentuates the majority of the spouts.

Underneath the spout is often the statue of Bhagiratha clutching a conch — a sage responsible for bringing the Ganga to the earth.

Legend asserts that the Ishvakian King Bhagiratha, from an ancient Indian dynasty successfully pleased Ganga after years of penance, who then agreed to descend to Earth. Since Ganga’s descent could lead to catastrophic consequences, she sought that only Lord Shiva could channelise her. Pleased by Bhagiratha’s prayer, Lord Shiva agreed to allow Ganga to flow from his hair.

The stone base resembling Bhagiratha is believed to be built beneath to support the weight of the long massive mouth of the stone spouts through which the water (Ganga) flows.

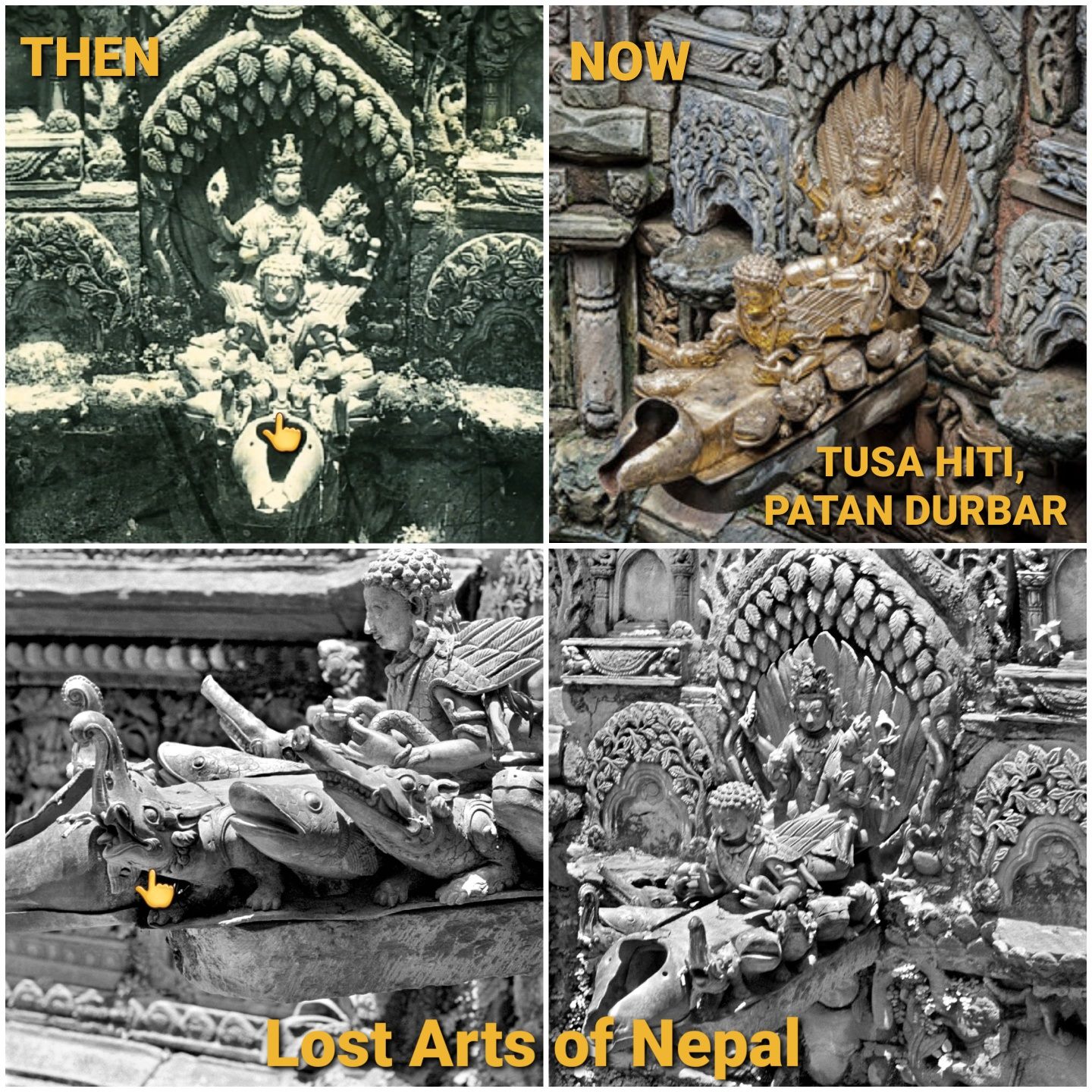

While the majority of spouts are made of stone, there are also gold-gilded hiti (Sundhara) usually spotted inside the royal palaces and built by Royal patronages. For instance — ‘Tusha hiti’ in Patan, ‘Mohan Chowk hiti’ in Kathmandu, and ‘Thanthu Durbar hiti’ in Bhaktapur. Some can also be found outside the regal premises such as Nuga: hiti in Patan, Sundhara in Kathmandu, and Taumadhi lun hiti Bhaktapur.

Hiti system often features one to three hiti manga: with elegantly engraved land and water animals — cow, goat, crocodile, frog, fish, and tortoise, among others. — down to the last detail.

In some hiti manga:, one can also catch a glimpse of hiti pusa — a lid to keep the water free of outer dust particles.

Tusha hiti

One of the most beautiful, Tusha hiti goes as deep as 150 centimetres from the level of the stone-paved Sundari Chowk of Patan Durbar Square and was laid by King Siddhi Narasimha Malla in 1647 CE to perform his ritual showers.

According to Sunil Pandey, a former docent at Patan Museum, “The pit, to which the monarch regularly offered water — as is customary in Hindu tradition — has 72 stone images of deities carved into its wall.”

He further added, “The walls of the pit are ornately decorated with the images of asta matrikas (eight mother goddesses) and asta bhairavas (eight angry manifestations of Lord Shiva). Tree trunks frame the separate niches of the Gods and Goddesses, with foliage hanging over them to create a canopy over the icons. Moreover, carvings of lingas and stupas around the base of the walls show religious tolerance in contemporary society.”

The periphery of the keyhole-like bath is guarded by two flare-hooded nagas (serpents) and two lions — one on each side, with a miniature Krishna temple replica at its central axis.

Dr. Deepak Shimkhada, in his paper “Tusha Hiti: The Origin and Significance of the Name” describes how the confounding water spout resembles a yoni (vulva) instead of a makara. Despite some similarities to the bovine form, the water spout is more reminiscent of an arghya patra — a ritualistic vessel for offering the water — than a cow’s head.

The water spout is topped by the image of Lakshmi-Narayana riding on Garuda (eagle-like demigod). The lateral faces hold chiselled portraits of a fish, a crocodile, a tortoise and a calf adding further allure.

It is believed that the water that flowed out of the spout tasted like sugarcane, and was given the name Tusha. Tu means sugarcane and sha — the flavour, in the Newari language (Nepal Bhasha).

In the present time, the flow of water has dried up in Tusha hiti.

The one that is currently on exhibit is a replica. The reproduction lacks two makaras and the three other figurines that were installed in the master hiti manga:

The original hiti manga: was stolen in 2010 A.D. but recovered a year later by the Nepal police. It is now showcased behind the glass cabinet in the Bronze Art Gallery at the National Museum of Nepal. The bottom conduit portion is missing.

Mohan Chowk hiti

Another iconic hiti is the Mohan Chowk hiti laid by King Pratap Malla in 1708 Bikram Sambat (1652 CE) at the centre of Mohan Chowk in Hanuman Dhoka Palace (known as Yen Durbar in Newari language).

According to Maya Devi Aryal, information officer at Hanuman Dhoka Museum, “The gold-gilded hiti was laid by the king for a favourable afterlife of royal bloodlines and to perform his ritual showers. It possesses 36 exquisite stone sculptures of different Gods and Goddesses along the inner wall of its hiti ga:”

The pit’s periphery is cordoned off by a white-coloured wall, two nagas, and two lions — one on each side — with a miniature Shikhar-style temple at its central axis.

At ground level, there is a Garuda statue in front of the spout.

When observing the ineffable hiti ga:, one can surmise that it resembles that of Tusha hiti — a conjecture that the King modelled the hiti to be competitive, owing to rivalry with his uncle.

The gold-gilded repoussé has its own enchantment comprising greater numbers of terrestrial and aquatic creatures — all appearing to be competing with one another towards the water exiting end.

At the adjoining point with the wall, a snake circumferences the spout. A pangolin figurine sits atop the spout, with a frog positioned below it.

Each lateral side comprises a bewitching detailed carved depiction of — an elephant’s head, a Cancer, a tortoise’s head with its shell and feet, a tiger’s head with its claw, a wolf’s head with its claw, a fish’s head with pectoral and dorsal fins, ear-raised rabbit and the upper body of a goat with its mouth open.

The mouth of the spout has the appearance of a calf escaping from the jaws of makara.

According to folklore, only the descendants of King Pratap Malla born within the premises of this hiti were eligible for the throne. It is believed that Jaya Prakash Malla who was born outside the hiti premises lost the city to Prithvi Narayan Shah for this reason.

There is another gold-gilded hiti inside the very palace at Sundari Chowk whose architecture is evocative of that of Mohan Chowk hiti.

Thanthu Durbar hiti

Upon divine revelation by Taleju Bhagwati, King Jitamitra Malla completed the construction of gold gilded hiti at Sundari Chowk of Khwopa’s Thanthu Durbar in 1683 CE, five years after its initiation.

The periphery of the rectangular-shaped pit is bounded by four flare-hooded nagas — two facing towards the east direction and two facing towards the west direction — with five miniature different-styled temples at its central axis (only 3 remain) above the hiti manga:. Behind these miniature temples is a gold-gilded bust of a naga.

There is a small pond in front of the spout, and at its centre is another gold-gilded statue of a flaring naga’s hood on a wooden pillar.

The protruding mouth of hiti manga: on an arched wall of hiti ga: combines a makara and a goat. The goat’s body appears to be inside the makara with prominent horns, ears, and two front legs. The goat’s mouth is wide open for the flow of water.

The lateral sides of hiti manga: are adorned with carvings of a human-like figure from the waist up with a tail and webbed feet, holding a Sinhamu (a ritualistic powder container) in its right hand. The figure has decorative hair, and a muscular face, and is adorned with various ornaments such as earrings, necklace, bangles, and a belt.

Similarly, the tightly composed statuette of frog, tortoise, conch shell, fish, ram, wolf, horse, duck, twisted snake, among others with a mongoose serving as the lid, creates a sense of overlapping and interplay between the different elements.

Below the carvings of creatures, Newari texts are carved on both sides.

Apart from magnificent gold gilded hitis of Royal palaces, one peculiar design can be found in Narayan hiti manga:

Contrary to the usual front curling, its trunk is positioned backward.

There is a tragic narrative about the reversal of the trunk of the Narayan hiti manga:

The tale revolves around a pious and righteous Licchhavi king who had earned the epithet Rajarsicharit, a king who possessed sage-like traits.

One ill-fated day, water from the hiti suddenly stopped flowing. His astrologer advised that only sacrificing a virtuous human with 32 attributes would resume the water flow. To his dismay, only he and his son qualified.

He then deviously commanded his son to strike down the person lying by the side of hiti covered with a white cloth from head to toe on the fourth day.

The son obeyed his father’s command. And the hiti resumed. But it was blood that poured out instead of water.

The baffled prince realised that the man he had sacrificed was his father. Not being able to witness a patricide, the hiti turned its trunk away.

The religion and culture

Hiti also manifests with fervent religious motifs with the majority of significant sculptures of the Hindu and Buddhist pantheons.

The carvings in the spout exhibit the cultural ideals of their architects, notably Licchavis who were migrants from the Gangetic plains of India. One of the most recognisable of the numerous religious and spiritual symbols is the crocodile — an emblem of purity and a native of the Ganges River.

The concept of Tusha hiti signifies a return to the sacred womb or a metaphorical rebirth. The pit and water spout in the courtyard of a palace is designed in the shape of a yoni (vulva), which is commonly associated with the Shiva linga — an abstract symbol representing Lord Shiva. Yoni is a symbol of the regenerating energy — Shakti. It is believed that Shiva’s existence is dependent upon Shakti. This Shiva linga paired with the Yoni is interpreted as a symbol of life, a concept frequently explored within the Tantric tradition.

Water, which is considered the source of life, is associated with the creative perspective of the female. The amniotic fluid in a woman’s womb, which nurtures and gives life to a child, is seen as a sacred creative power and is venerated in the form of a goddess. The act of bathing with this water flowing from hiti can be symbolically viewed as a rebirth or regeneration.

The water from the left spout of Patan’s Manga hiti is used for reviving Hiranyakashipu in the Kartik Naach which is enacted at the Patan Durbar Square every year in the month of Kartik, while the water from its right spout is required for the daily ritual worship of the Krishna temple.

Bhaktapur offers water from its Thanthu Durbar hiti to goddess Taleju and serves those joining Shiva Ratri from Bhimdyo hiti.

Festivals occur in Balaju Baais-dhara in the month of Chaitra Purnima, and every twelve years in Godavari Nau-dhara where numerous devotees take bath to cleanse the soul and purify the spirit for peace, solace and healing.

The most important festivals related to the water system are Sithi nakha and Machhindranath Jatra.

Sithi nakha falls in May, just before the monsoon, and is a day dedicated to cleaning and repairing the water system — hitis, wells, and ponds.

It is a prevalent belief that the proper functioning of hiti depends on the well-being of its Naga (snake-like being). Whenever the conduit is blocked, the locals believe it to be caused by naga due to misuse of conduit such as doing laundry and taking baths.

The Naga deities that live in these water sources are said to emerge from their dwelling on this precise day allowing for the uninterrupted upkeep of these water sources. After cleansing, it is then left for four days. No one is permitted to access water from these sources for the next four days.

The relevance of hiti is also reflected in music, art and public imagery.

Thane yā Thahiti, kwane yā Kwahiti

Biche lāka Maruhiti

Maruhiti la kā wonha, tagwa lohtey lupin hānā

Rājamati thasa pāla nhā

This verse from the renowned Newari language song “Rajamati kumati” by late legendary Nepali singer Mr. Prem Dhoj Pradhan aptly describes the hitis in Kathmandu city which can be translated as —

Tha: hiti is in uptown, Kwa: hiti is in downtown

Maru: hiti is in between them

When Rajamati went to fetch water from Maru: hiti,

She stumbled into a stone and laid flat

Among other murals, the front gate’s perimeter wall at the British Embassy, Kathmandu features Manga hiti, while that of Nepal Telecom showcases Sundhara present within the Bhimsen Tower (Dharahara) premises.

The Tragedy: Disappearing hiti

Tragically, this age-old magnificence has massively depleted over the decades and is on the brink of disappearance.

New hitis gradually declined in construction after Prithvi Narayan Shah conquered the valley.

A limited number of spouts were constructed during the Rana regime.

As time passed, spout water was progressively abandoned due to the acculturated notion that they were unsafe and contaminated with the Ranas and later elected rulers promoting the use of private taps since the 1950s. This then led to the use of municipal water supplies to replace public traditional sources.

The following series of photographs reveal how the ancient waterspout has now instead become a wasteland [photos taken a year ago] due to local indifferences and the state’s neglect. Many ancient waterspouts have become a wasteland due to local indifferences and the state’s government neglect.

After Mohan Chowk crumbled following the terrible 2015 earthquake, the museum ceased to allow visitors. Nine years have passed since. Yet when I enquired about the estimated timeline of the necessary renovations, I was given a solemn response that it would be done shortly.

The Thanthu Durbar hiti is not in its original state except for its pillar with the snake and its position. The peripheral nagas had taken severe damage. Even though some repairs have been done, the originality has vanquished — depicting an abysmal management from the concerned authorities. On the left side of hiti manga:, a creature carrying a sinhamu, has a sizable hole in its body.

Outside museums and durbars, many hiti have dried up or have lesser water flow due to the rapid and unplanned urban development. They have eaten up trees, encroached open spaces and installed modern structures including highways, buildings and deep boreholes — inconsiderate of how it would impact the flow of water in those stone spouts.

Traditional water infrastructures such as state canals and ponds have been encroached upon too. The canal is covered to make vehicular roads, concealing the water systems and further increasing the risk of neglect.

Households directly discharge wastewater to the canals, which ultimately pollute pond water either by direct connection or infiltration. Ponds have also become stagnant due to improper reconstruction processes such as cemented stone walls and lack of inlet-outlet points.

A 2019 study documented 573 spouts in the Valley, noting that 94 had disappeared entirely. Among the remaining, only 224 were functional, likely due to dropping groundwater levels and the obstruction of flow caused by deep-foundation construction.

In their crumbled state, they are now listed in the 2022 World Monuments Watch — a list of 25 globally significant heritage sites in urgent need of preservation.

Recognising the critical state of the hiti system, the Kathmandu Metropolitan City (KMC) launched a Dhungedhara Hiti Pokhari Conservation Program to restore and maintain these ancient water structures across its 32 wards. In Naxal locals reopened a hiti water outlet, resolving a 40-year issue of conduit blockade, under the KMC administration.

However, addressing the valley’s water crisis which has also made hiti dysfunctional requires more than conservation. Groundwater, the primary source for up to 70% of Kathmandu Upatyaka Khanepani Limited’s (KUKL) dry-season supply, is overexploited. With a daily demand exceeding 320 million liters, the municipal supply remains insufficient, forcing households, businesses, and industries to rely heavily on private groundwater extraction.

This is unsustainable and has caused rapid depletion of the water table. While recharge systems are critical, efforts remain limited. The Rajkulo and traditional ponds — once vital for sustaining water systems — have largely fallen into disrepair. For instance, a canal in Godawari Municipality remains blocked for most of the year, functioning only briefly during rice planting season.

In contrast, the successful restoration of Nigu Pukhu in Bhaktapur offers a new promise. Once dried up and repurposed for cultural events, the ponds were revitalised in 2018 through a collaborative effort between the municipality and the community. Initially refilled with borewells, they now sustain naturally.

Inspired by this success, Thimi Municipality restored 11 ponds and 25 spouts in 2021.

These efforts offer modest but hopeful prospects of reviving a system that embodies a remarkable and magnificent heritage and engineering legacy. But it is also a crucial piece of water infrastructure vital to the valley’s very survival.

“It is the nature of our world that civilizations founder and pass. But in this case, I have tried to read the past from the rapidly changing present before it is too late.”

- Dr. Mary Shepherd Slusser in Nepal Mandala: A Cultural Study Of The Kathmandu Valley

The text in this work entails a moderate amount of editing and refining using AI technology but no part of it was generated using it. The structure was finalised based on discussion with the editorial and accuracy and clarity was maintained through the review of several scholarly works and reports, field visits and interviews.

Edited by Sabin Jung Pande

Read More Stories

Kathmandu’s decay: From glorious past to ominous future

Kathmandu: The legend and the legacy Legend about Kathmandus evolution holds that the...

Kathmandu - A crumbling valley!

Valleys and cities should be young, vibrant, inspiring and full of hopes with...

The majestic Upper Mustang and its water troubles

The wind stirs heavily across the barren landscape as our bus pushes along...